ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΡΑΒΙΚΗ ΠΟΙΗΣΗ ΚΑΙ ΚΑΡΑΓΚΙΟΖΗΣ

Posted on Jan 10, 2017 |

ΣΕ ΑΥΤΗΝ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΣΕΛΙΔΑ ΤΗΣ Η HELLENIC POETRY ΑΠΟΔΙΔΕΙ ΕΝΑ ΦΟΡΟ ΤΙΜΗΣ ΣΤΟΝ ΣΥΡΙΟ ΠΟΙΗΤΗ ΑΔΩΝΗ.

ΠΑΡΟΥΣΙΑΖΟΥΜΕ ΚΑΠΟΙΑ ΠΟΙΗΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΕΤΑΦΡΑΣΜΕΝΑ ΣΤΑ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΑ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΒΙΒΛΙΟ ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ, ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

ΟΠΩΣ ΕΠΙΣΗΣ ΚΑΠΟΙΑ ΠΟΙΗΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΕΝΕΛΑΟΥ ΚΑΡΑΓΚΙΟΖΗ ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΑ ΑΠΟ ΤΑ ΠΑΡΑΠΑΝΩ ΠΟΙΗΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΑΔΩΝΗ.

Ο σπουδαίος αραβόφωνος ποιητής Άδωνις έρχεται στη Στέγη 10/01/2017

Με Βραβείο Goethe, διεκδικητής επί χρόνια του Νόμπελ Λογοτεχνίας, αυτοεξόριστος από τη Συρία και ένας από τους μεγαλύτερους ποιητές του Αραβικού Κόσμου, ο Άδωνις έρχεται στη Στέγη.

Ο Άδωνις, ένας από τους μεγαλύτερους ποιητές του Αραβικού Κόσμου, έρχεται στη Στέγη του Ιδρύματος Ωνάση στις 10 Ιανουαρίου για μια συζήτηση με τον Γιώργο Αρχιμανδρίτη για την αραβόφωνη ποίηση σήμερα, για τον ρόλο της ποίησης στην εποχή μας, για γεωπολιτικά θέματα, όπως τον πόλεμο στη Συρία, για το προσφυγικό, το Ισλάμ, τον θρησκευτικό φονταμενταλισμό και την τρομοκρατία.

Ο Άδωνις έχει τιμηθεί με το Βραβείο Goethe, μια από τις πιο σημαντικές διακρίσεις πολιτισμού στον κόσμο, «για το διεθνή χαρακτήρα του έργου του και για την προσφορά του στον παγκόσμιο πολιτισμό» (όπως πριν από αυτόν ο Thomas Mann, ο Hermann Hesse, η Pina Bausch ή ο Ingmar Bergman), ενώ συγκαταλέγεται εδώ και αρκετά χρόνια ανάμεσα στους διεκδικητές του Βραβείου Νόμπελ Λογοτεχνίας.

Ο Άδωνις γεννήθηκε το 1930 στη Συρία ως Ali Ahmed Saïd Esber, αλλά ήδη από την εφηβική του ηλικία υιοθέτησε το μυθολογικό ψευδώνυμο Άδωνις με το οποίο γρήγορα έγινε γνωστός, θεωρώντας πως η απέκδυση του μουσουλμανικού του ονόματος δίνει συμβολικά πρόσβαση στην οικουμενικότητα και την πράξη της δημιουργίας. Καταδικασμένος σε φυλάκιση στην πατρίδα του λόγω των προοδευτικών πολιτικών του πεποιθήσεων, ο Άδωνις αυτο-εξορίστηκε στον Λίβανο και στη συνέχεια στο Παρίσι όπου ζει μέχρι σήμερα.

HUFFINGTON POST

Adonis Interview: I Was Born for Poetry

![maxresdefault[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/maxresdefault12-300x168.jpg)

ΤΟ ΚΕΛΥΦΟΣ

Στα ματόκλαδα πέρασε το πρόσωπο της πόλης,

χαμένο κάτω από τον πάγο των προσωπείων

κι ανακράξαμε:

εμείς ζούμε στα άντρα της πόλης

καθώς το σαλιγκάρι μέσα στο κέλυφος του,

ω άρνηση, ανακάλυψέ μας!

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

ΦΩΝΕΣ ΑΧΤΙΔΕΣ ΚΙ ΑΓΕΡΗΔΕΣ

Μήπως βλέπουν τόσα απομεινάρια πολιτισμού

όλα αυτά που γεννιούνται μα απότομα

σβήνουν σαν μέλλον απραγματοποίητο;

πίσω από το σκοτάδι δημιουργούνται φωνές, αχτίδες κι αγέρηδες

έτσι θέλησε η φύση κι ας είμαι εγώ μόνος

πως αλλιώς θα σιγουρευτώ ότι δεν ριψοκινδυνεύει η ζωή εξαιτίας μου

όξω ένα πρωινό γιομάτο αίμα περιμένει κάποιον

μέσα η νύχτα αλάβωτη ακόμη

τούτος ο λόγος ανακράζει όπως

μια γλώσσα παράλυτη χωρίς ανάστημα

μα δίχως φως κανείς για να με δει

μονάχα λίγο άσμα ντροπαλά σιωπηλό

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΕΞΑΡΧΕΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ ΜΕΤΑ ΤΗ ΣΙΩΠΗ, ΣΕΛ. 104

![f04da2db1122137cf9e232[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/f04da2db1122137cf9e2321-300x282.jpg)

ΕΠΙΣΤΟΛΗ

Η χώρα που ονειρευτήκαμε και προς αυτήν χαράξαμε

δρόμο,

ορίζοντας από τα δειλά βλέφαρα πληγωμένος·

χτες, στην περηφάνια της φιλικής τρέλας

και στην τελείωση της νιότης,

χτες τη λαχταρήσαμε και ζωγραφίσαμε

εν ονόματί της εικόνα και φωτοστέφανο,

της γράψαμε μιαν επιστολή-

χώρα πληγωμένη από τα δειλά βλέφαρα.

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![karagiozi2[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/karagiozi21-300x204.jpg)

ΜΑ ΓΗ ΠΟΥΘΕΝΑ

Ένα ευαγγέλιο σκουριασμένο όπως ο οδοιπόρος τούτος

στο μονοπάτι της άρνησης

δημιουργός δίχως πρόσωπο θα τον έλεγες

ξάφνου εμφανίστηκε κάποια χώρα σ’ ένα χάρτη

μα γη πουθενά

εγώ χωρίς φακό κι όμως άφησα ουρανό πολύ πίσω μου

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΕΞΑΡΧΕΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ Ο ΟΔΟΙΠΟΡΟΣ, ΣΕΛ. 102

![467341746[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/4673417461-300x200.jpg)

Ο ΟΡΦΕΑΣ

Ερωτευμένος, κυλάω σαν πέτρα

μες του Άδη το ζόφο

κι όμως φεγγοβολώ·

με τις μάγισσες θ΄ανταμωθούμε

στην κλίνη του παλιού θεού·

άνεμοι που ταράζουν τη ζωή τα λόγια μου,

σπινθήρες τ’ άσματα μου·

είμαι η γλώσσα κάποιου ερχόμενου έχθρου,

ο γητευτής του κουρνιαχτού.

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![karagiozi2[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/karagiozi21-300x204.jpg)

ΑΠΑΝΩ ΣΟΥ Ο ΘΕΟΣ

Είναι ο ουρανός γιομάτος άνεμους ακατάκτητους ακόμη

κι αετούς ερήμου

πάνω στους σπόρους της γέννησης

εγκατεστημένους

σκύβω να προσκυνήσω λίγη άμμο ή ελάχιστο σύννεφο

τα πράγματα δίχως γη αναπνέουν

πρωταρχικά κοντά στους ήλιους

η τρέλα ως πράσινη εικόνα

κι ο φτερωτός κεραυνός πόσο μοιάζουν

μονάχα ο βράχος αδελφέ μου

μονάχα τούτος μας περιμένει

ενώ ο χάρτης κομματιασμένος σε χωράφια

είτε άβατους βάλτους

έρχεται τώρα μια άβυσσος

άλλαξε λοιπόν βλέφαρα ή βλέμμα

αν δεν θέλεις να καταρρεύσει απάνω σου ο θεός

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΕΞΑΡΧΕΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ Ο ΚΕΡΑΥΝΟΣ, ΣΕΛ. 103

![Part-PAR-Par8128369-1-1-0[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Part-PAR-Par8128369-1-1-01-300x199.jpg)

Ο ΙΣΚΙΟΣ ΜΟΥ ΚΙ Ο ΣΚΙΟΣ ΤΗΣ ΓΗΣ

Πλησίασε, ουρανέ, κι αναπαύσου

στον στενό μου τον τάφο,

στο πλατύ μου το μέτωπο,

στάσου δίχως πρόσωπο και χέρια,

χωρίς ψυχορράγημα και παλμούς,

ζωγράφισε τον εαυτό σου εις διπλούν-

τον ίσκιο μου και τον ίσκιο της γης.

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![024_efi[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/024_efi1-244x300.jpg)

ΑΝΑ ΠΑΣΑ ΣΤΙΓΜΗ

Μου ψιθύρισε μια καμπάνα

που ήταν λύκου η καινούργια φωνή

«θεϊκό πρόσωπο περιπλανιέσαι

οι ψυχές συντρίβονται όπως η νύχτα στο φεγγάρι»

ο θάνατος ήμου κάποτε εγώ

ώσπου γεννήθηκα

κι έτσι απλά, αδιαμαρτύρητα, εκείνος πέθανε

με καμένες λέξεις και κάρβουνo στίχων

οι πνευματικές φωτιές φλογίζουν τη ποίηση

όμως ανά πάσα στιγμή

όλα τα πράγματα μπορεί ν’ αντιστραφούν

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΠΑΤΗΣΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ Ο ΘΕÏΚΟΣ ΛΥΚΟΣ, ΣΕΛ. 105

![Screen-Shot-2015-05-20-at-00.03.57[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Screen-Shot-2015-05-20-at-00.03.571-300x191.png)

Ο ΘΕÏΚΟΣ ΛΥΚΟΣ

Με καμένο πρόσωπο, το πρωί περιπλάνιεται,

κι εγώ, του φεγγαριού ο θάνατος·

κάτω απ΄το πρόσωπό μου συντρίφτηκε της νύχτας η

καμπάνα,

κι εγώ, λύκος καινούργιος θεϊκός.

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![Karagkiozis[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Karagkiozis1-269x300.jpg)

ΧΩΡΙΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΑ ΛΟΓΙΑ

Στα χαλάσματα εμείς βρήκαμε λάσπες

έφραξαν εκεί τις οδύνες

οι λέξεις όμοια φωτοστέφανα φευγάτα

σιωπούσαν

σαν καμένες λάμπες νεκρών αγγέλων

η γλώσσα εκόσμησε τους ανθρώπους

εδώ και χρόνια

μ’ ελεγείες και μετάνοιες όσων ειπώθηκαν

μα θα μου πεις βλαστήμια είναι τούτο εδώ το πράγμα

κι όχι ποίημα

ξεσπάσανε στο γέλιο οι ακρίδες

βροχή ήταν στολισμένες

κάποιο ξεσκέπαστο σύννεφο ροχάλιζε όπως τ’ άστρα

εγώ όμως πιστεύω σ’ ένα χείμαρρο γνώσεων

γύρισε πίσω τώρα μέλλον

ιδού η μεγάλη σου αποστολή

κοίταξε πιο πέρα απ΄ ότι έφτασες

είπαμε όλοι εμείς ας αποχαιρετιστούμε

χωρίς μεγάλα λόγια

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΠΑΤΗΣΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 07/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ ΑΠΟΧΑΙΡΕΤΙΣΜΟΣ, ΣΕΛ. 152

![Part-PAR-Par8128369-1-1-0[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Part-PAR-Par8128369-1-1-01-300x199.jpg)

Η ΓΗ ΤΗΣ ΑΠΟΥΣΙΑΣ

Ιδού η γη της οδύνης

δίχως αύριο μήτε άνεμο φωτεινό·

ποιά φωνή θα φτάσει

ω αγαπημένοι μου στη γη της απουσίας;

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

ΣΑΛΙΓΚΑΡΙ

Κάθε σαλιγκάρι είναι μια άρνηση θανάτου

ω σ’ εκλιπαρώ

ανακάλυψε μας ζωή πριν γεράσουμε

σερνόμαστε εδώ στην ανάσα της πόλης τούτης

κέλυφος πάγου η ψυχή

τόσα προσωπεία χαμένα στις σκέψεις

σαν πεταλούδες

κάτω στο υπόγειο η θέα καθώς ζαρώνει γίνεται άρνηση

ματόκλαδα μοναξιάς και πίκρας

ανακράξαμε όλοι μαζί υπάρχουμε

περνά μακριά πολύ η μοίρα

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΠΑΤΗΣΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 07/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ ΤΟ ΚΕΛΥΦΟΣ, ΣΕΛ. 155

![f04da2db1122137cf9e232[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/f04da2db1122137cf9e2321-300x282.jpg)

Ο ΒΡΑΧΟΣ ΤΟΥ ΚΕΡΑΥΝΟΥ

Είμαι ο βράχος του κεραυνού,

ο θεός, που το χαμένο ανταμώνει σταυροδρόμι,

σημαία, κρεμασμένη στα βλέφαρα του πλανώμενου

σύννεφου,

κρεμασμένη στα βλέφαρα της τραγικής βροχής,

ο πλανώμενος που πορεύεται, χείμαρρος και φωτιά,

κι αναδεύει τη σκόνη με τον ουρανό,

η φωνή της αστραπής και του κεραυνού.

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![kantada%20ΟΛΟΙ[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/kantada-ΟΛΟΙ1-300x132.jpg)

ΣΕ ΠΟΙΟΥΣ ΔΡΟΜΟΥΣ;

Πόσο τα βλέφαρα διψούνν για φωτοστέφανο κι εικόνα

μια επιστολή μας έγραψε η νιότη

πάνω εκεί ζωγραφίσαμε τέλειες ρυτίδες

λαχταρήσαμε λίγη περηφάνεια

του χτες εμείς οι πληγωμένοι απόγονοι

τρέλα δειλή κι όμως τη λογική ορίζεις

που να ‘ναι η χώρα;

εν ονόματι αυτής

χαράξαμε όνειρα κι ελπίδες

που ‘ναι τώρα σε ποιούς δρόμους;

άραγες βαδίζει ακόμη;

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΠΑΤΗΣΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 07/01/2017

ΤΟ ΚΟΧΥΛΙ

Τρόμαξες; άλλαξε το νικημένο σου πρόσωπο,

ω δαίμονα κι άρμα πάνω από τα αστέρια!

βουβός ο δρόμος δεν με φοβίζει,

είμαι ο καυτός αγέρας,

είμαι σαν το κοχύλι:

κάτω απ’ το πρόσωπο μου σκάφτηκε ο δικός μου ο

τάφος·

άφησε τα όνειρα μες στα τρεμάμενα σου ματόκλαδα

και μείνε στο λαιμό μου,

ω δάιμονα κι άρμα κάτω από τα αστέρια.

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![Dalianoudi_Karagiozis_9[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Dalianoudi_Karagiozis_91-300x197.jpg)

ΕΥΧΗ ΣΚΟΝΗΣ

Στην ερημιά οι πάνε άνεμοι να σβήσουν τις ψυχές τους

ενώ εμείς ψιθυρίσαμε σημαίες και δάφνες

σαν ευχή σκόνης

κουβαλάγαμε επανειλλημένα ό,τι μας ακολουθούσε

ξοπίσω ο τρόμος αργός μα φεγγοβόλος

συχνά ανάμεσα από δρόμους

τις πιο πολλές φορές εχθρικούς

εγώ ονειρεύομαι πως βρίσκω λίγα βήματα αδελφικά

εκεί ακριβώς ξυπνάω

σταματάω μπας και ξαποστάσω

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΚΟΛΙΑΤΣΟΥ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 07/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ ΦΕΓΓΟΒΟΛΟΙ ΑΝΕΜΟΙ, ΣΕΛ. 154

![Screen-Shot-2015-05-20-at-00.03.57[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Screen-Shot-2015-05-20-at-00.03.571-300x191.png)

Η ΜΟΝΑΔΙΚΗ ΓΗ

Κατοικώ ετούτα τα πλανώμενα λόγια

και ζω παρέα με το πρόσωπό μου,

το πρόσωπό μου, σύντροφος και οδός·

στ’ όνομά σου, γη που μακαραίνεις

μαγεμένη, μοναδική,

στ’ όνομά σου, ω θάνατε ω φίλε μου.

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![024_efi[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/024_efi1-244x300.jpg)

ΠΥΡΠΟΛΗΜΕΝΟ ΠΡΟΣΑΝΑΤΟΛΙΣΜΟΥΣ

Ευχήσου κλαδί του χρόνου να μην μαραθώ

σαν δένδρο που ζει μέσα στη φωτιά

στο μέτωπό σου ο πυρετός είναι απώλεια

κι όμως εμένα με προστατεύει

ο ορίζοντας εκείνος τόσο μακρινός

θα είχα πιστέψει στα σύννεφα

αν η άβυσσος δεν ακουγόταν λυπημένη

ίσως γινόμουν αγκυροβόλι θλίψης

πίσω από κάθε πρόσωπο

ανοίγεται ο χρόνος στα φτερά του

ωστόσο η χώρα τούτη που μας γεννά

δεν είναι παρά ευχή κέδρου

ρίζωσα τώρα στις φλούδες των δένδρων

ήμουν βλέπετε κι εγώ πιστό φύλλο

όχι ένας τόπος μα ακτίνα

ιστίο ήλιου κατάρτι

ταξίδι πυρπολημένο προσανατολισμούς

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΓΑΛΑΤΣΙ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ ΕΥΧΗ, ΣΕΛ. 76

![maxresdefault[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/maxresdefault12-300x168.jpg)

Η ΗΤΤΑ

Σας μεταπλάθω τώρα, άσματά μου,

σε σύννεφα, ελεγείες και βροχή

το φόνο αναδεύω με τη χάρη

πλέκοντας με τις λόγχες της ήττας

τη σημαία του χώματος και της αυγής·

βασίλειο μου η μαγεία, η φωτιά

και η ευωχία· ο στρατός μου

η ομίχλη· και ήττα ο κόσμος.

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![karagiozi2[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/karagiozi21-300x204.jpg)

ΑΝΤΙΛΑΛΟΣ

Αντίλαλος από κεριά

αγίων άσπρο σπλάχνο

μυριάδες μοίρες

έσβησα τους ήλιους

γεύομαι βουνά και κύματα

ντυμένος στο σκοτάδι

η οδός του ουρανού μου είπε συννέφιασα

κι εσείς πρόσωπα κυανωπά παραδοθείτε

στα δόντια κόψτε ό,τι με κρατά δεμένο

σκοινιά της εσχάτης όχθης

έστω και λίγος ο θαλασσινός ορίζοντας

κύμα, ακρογιάλια, ουρανούς

όλος εκεί μέσα ο ρόγχος

του ‘πα φύγε

δεν έχω να σου δώσω

παρά μονάχα πλούτη ζωής

λίγης ποίησης πολύ το νόημα

απαλύνει τα τόσο στενόχωρα όρια

της κάθε ψυχής και βράχου

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΠΑΤΗΣΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ Η ΓΕΦΥΡΑ ΤΩΝ ΔΑΚΡΥΩΝ, ΣΕΛ. 72

Η ΓΡΙΑ ΧΩΡΑ

Σε βράχους και αχούς

παρέδωσε τις στραγγαλισμένες μου σημαίες·

τις παρέδωσε στην ακρόπολη της σκόνης,

στης άρνησης και της ήττας την περηφάνεια·

από σένα άλλο δεν μου απέμεινε,

γριά και μυστική μου χώρα.

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![Karagkiozis[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Karagkiozis1-269x300.jpg)

ΚΑΘΕ ΣΤΙΓΜΗ

Στους βράχους κυοφορούν οι νύχτες

δημιουργώντας έτσι πατρίδα

έστω και χωρίς φεγγάρι ή ρίζες ουρανού

στάχτες κι άστρα κυνηγιούνται

σύννεφα λείψανα των ωκεανών

κεραυνός ερωτευμένος δάση

αιώνες από βουνά καίγονται κάθε στιγμή

σε χωράφια κομμένη και χωρισμένη η θάλασσα

δημιουργώντας απουσία

ερωτευμένη όπως η βροντή το κύμα

ασμάζεται κι ανοίγουν οι πόρτες

για να θαφτεί μέσα εκεί η γη

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΠΑΤΗΣΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ Η ΠΑΡΟΥΣΙΑ, ΣΕΛ. 64

![467341746[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/4673417461-300x200.jpg)

ΓΥΡΕΥΩ ΤΟΝ ΟΔΥΣΣΕΑ

Πλανώμαι σε σπηλιές με θειάφι,

αγκαλιάζω τις σπίθες,

ξαφνιάζω τα μυστήρια

μέσα στο σύννεφο του λιβανιού, στα νύχια του

δαιμόνου-

γυρεύω τον Οδυσσέα,

ίσως μου στήσει σκάλα τις μέρες μου,

ίσως μου φανερώσει ό,τι αγνοεί το κύμα…

© ΑΔΩΝΙΣ, ΑΣΜΑΤΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΙΧΙΑΡ ΤΟΥ ΔΑΜΑΣΚΗΝΟΥ

ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΑΓΡΑ, 1996

![kantada%20ΟΛΟΙ[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/kantada-ΟΛΟΙ1-300x132.jpg)

ΣΕ ΚΑΠΟΙΟ ΑΣΜΑ

Η ζωή ενός παλιού θεού

γίνεται κλίνη για λόγια κι όνειρα

άνεμοι σπινθηρίζουν

όπως η γλώσσα καθώς κουρνιάζει

στη ποίηση

γητευτής και μάγισσα συνάμα

φεγγοβολά η πέτρα

όταν είνα κομμάτι κάποιου στίχου

κυλάει ο ερχόμενος θεός

όλοι μας ερωτευμένοι μαζί κι ο Ορφέας

ίσως συναντηθούμε σε κάποιο άσμα

κι ας είναι ζοφερό του Άδη

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΚΥΨΕΛΗ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ Ο ΟΡΦΕΑΣ, ΣΕΛ. 66

![Dalianoudi_Karagiozis_9[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Dalianoudi_Karagiozis_91-300x197.jpg)

ΞΑΝΑΔΙΑΒΑΖΩ

Σπήλαια εκεί οι πρωτανθρώποι

χτίσαν βασίλεια

ερείπια-τεκέδες

φράγματα στον χρόνο

πόσο εκείνα προσφέρουν ζωή σε μνημεία

και μέλλον γιομάτο λείψανα

δεν υπάρχουν θύματα

μονάχα βλέφαρα αλήθειας

άσμα ο χορός σου γέννηση γης

έχει και το πρόσωπο φλέβες

αποβολή αστεριού κι ένα φως γεννιέται

κληρονομιά μου αιώνια στα βράχια θα σε βρω

φέγγεις κενό κι η γλώσσα αφέντισσα

στους άνεμους δοσμένη

ξεχύνονται οι χώρες διαστάσεις απειροελάχιστες

φλούδα πολέμου, κάτω απ` το βλέμμα

ξαναδιαβάζω ό,τι έγραψε η ψυχή

πρωί ανέκαθεν πρωί πεθαίνω

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΠΑΤΗΣΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ ΤΑ ΦΡΑΓΜΑΤΑ, ΣΕΛ. 74

![024_efi[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/024_efi1-244x300.jpg)

ΑΟΡΑΤΟ ΣΤΟΥΣ ΚΑΘΡΕΦΤΕΣ

Ο θάνατος κάποιου φίλου

μαγεμένος κλειδώνεται στο όνομά του

συντροφεύεις τώρα τη γη

νεκρός καθώς μακραίνεις

οδός προσώπου λίγη

στα βλέμματά μας φανερωμένη

παρέα κατοικούμε νεκροί και ζωντανοί

ανασαίνουμε πέρα από κάθε γέννηση

ετούτα όσα λέω μοναδικά

σαν κάτι αδύνατο να συμβεί

αλλά να πραγματοποιείται κάπου

έστω κι άφαντο

αόρατο στους καθρέφτες όμως

χαμογελά αφού εγώ το βλέπω

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΠΑΤΗΣΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ Η ΜΟΝΑΔΙΚΗ ΓΗ, ΣΕΛ. 75

ΕΙΜΑΙ Ο ΔΟΥΛΟΣ ΣΟΥ

Η βροχή με χάρη είναι ήττα κάθε αυγής

ο νυχτερινός φόνος που μ΄ αναδεύει σαν ανάσταση

ελεγείες μεταπλάθω τώρα

σε σύννεφα ασμάτων

πλέκοντας υφάσματα από λόγχες

η σημαία πια θαμμένη στο χώμα

άξιος νεκρός

μαγεία βλέπεις ο θάνατος

ξαναζωντανεύει τον άνθρωπο

φωτιά ομίχλης ο κόσμος

βασίλειο μου η μάχη

που δίνεις εσύ καρδιά

κι ας είναι η τσέπη άδεια και φαρδιά

χτύπα, χτύπα και μαστίγωνε με

εγώ είμαι ο δούλος σου

στρατιά πόνου είσαι από μόνη μια οχιά

κι η γνώση των αιώνων ευωχία

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΠΑΤΗΣΙΑ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ Η ΗΤΤΑ, ΣΕΛ. 78

![karagiozi2[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/karagiozi21-300x204.jpg)

ΓΥΡΕΥΩ ΛΙΓΟ ΜΕΛΛΟΝ

Νύχια γιομάτα οι σπίθες

μέρες φανερωμένες στα κύματα

μυστήρια ουρανού λιβανίζουν σύννεφα

δαιμονισμένες σκάλες

ό,τι ύψος αγνοείς Οδυσσέα

στήθηκε θειάφι πολύ μπρός στην σπηλιά

κι εμείς πλανιώμαστε αγκαλιασμένοι

ξαφνιάζεσαι μέσα από κάποια μήτρα καθώς βγαίνεις

μπορεί ίσως έμβρυο να ξαναεπιστρέψεις κάποτε εκεί

στήσου στις μέρε μου μπροστά

γυρεύω λίγο μέλλον όπως ο καθένας μας

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΓΑΛΑΤΣΙ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ ΓΥΡΕΥΩ ΤΟΝ ΟΣΥΣΣΕΑ, ΣΕΛ. 78

![Karagkiozis[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Karagkiozis1-269x300.jpg)

ΗΤΤΗΘΗΚΑΜΕ

Η ακρόπολη πλέον

αντιπροσωπεύει ό,τι σας απέμεινε

χώρο σκόνης δηλαδή και τσιμέντου

αρχαία περηφάνεια η σημαία αρνείται να γεράσει

από σένα δε θέλουν τίποτα άλλο οι θεοί

παρέδωσε τους τα μυστικά των βράχων

ηττήθηκαμε λοιπόν μας νίκησαν αχοί ποιητικοί

στραγγαλισμένες οι φωνές σου

χώρα μου στο λαρύγγι

©MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY,

ΓΑΛΑΤΣΙ, ΑΘΗΝΑ, 09/01/2017

ΕΜΠΝΕΥΣΜΕΝΟ ΑΠ’ ΤΟ ΠΟΙΗΜΑ Η ΓΡΙΑ ΧΩΡΑ, ΣΕΛ. 83

MY SYRIA

The Syrian poet, critic and artist Adonis has been described as the greatest living Arab poet.

He was the first Arab to win the German Goethe Prize last year at the age of 81, whose judges described him as “the most important Arab poet of our time,” and he was one of the favorites to win last year’s Nobel Prize for Literature.

Adonis, born Ali Ahmad Said Esbar, grew up in a poor village near the Syrian city of Latakia and received no formal education until he was granted a scholarship to a French lycee by the then president of Syria at the age of 13.

He was forced to leave Syria in 1956 after being imprisoned for his involvement in the opposition Syrian National Socialist Party. He moved to Beirut, Lebanon, and now lives in Paris and Beirut.

He spoke to CNN through an interpreter at an exhibition of his collages and a series of literary events called “A Tribute to Adonis” at the Mosaic Rooms in London until March 30.

CNN: How do you feel watching the situation in Syria?

Adonis: I’m very sad. I wish that the regime would understand that it has to reform or renew itself and create a new government through free and fair elections.

I also wish that the opposition had not resorted to armed violence because I’m personally against violence in all its forms. I do not see any justification for its use whatsoever.

CNN: Should the outside world intervene in Syria?

A: The world should not interfere, especially not militarily. The Western world should not use this as a pretext to fulfill its own goals in the region.

More from Inside the Middle East: Filmmaker Nigol Bezian’s tour of ‘Little Armenia’ in Beirut

CNN: Are you in touch with friends in Syria?

A: I last went to Syria a year and a half ago, but I’m always in touch with my friends there. Many of them are in the opposition — but in the peaceful opposition. Many of them share my views that the solution must be Syrian and through a democratic dialogue. We must reach a new regime that is democratic, plural and secular.

CNN: Are your friends scared?

A: Their main fear is for the violence and for the potential for the situation to develop into civil war. They are not scared to speak out. They can talk openly.

CNN: How have events of the past year changed the Arab world?

A: There’s definitely a new consciousness everywhere. The question is will this lead to a new political reality and new regimes? It’s difficult to predict, but I hope so.

CNN: Have you seen changes in Lebanon, where you have lived on and off since 1956?

A: Lebanon will remain as it has always been: An ongoing project, a work in progress. It’s a project that’s difficult to stop, but it’s equally difficult to continue with.

CNN: You received no formal education until you recited one of your own poems to the then Syrian president in 1943. How did that happen?

A: It was almost 70 years ago after Syria became independent and the president was touring the country. I was 12 or 13 and I read a poem in front of the president. He called me over and asked what I wanted. I said I would like to go to school, so I got a scholarship to a school in Latakia.

More from Inside the Middle East: Women and the Arab uprisings: 8 ‘agents of change’ to follow

CNN: How did that change your life?

A: Poetry gave me a new life. I can always say that poetry allowed me to be reborn.

CNN: How important is poetry in Arab culture?

A: There are two things that are central to our culture: Religion and poetry. They were always in conflict. Unfortunately now religion is overwhelming poetry, but I have a saying that poetry remains deeply-rooted and strong. Poetry has never had any influence throughout history, however poetry creates a new aesthetic, a new beauty, a new type of relations between things and people, and this is not insignificant.

CNN: What was Syria like before 1970 when Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father came to power?

A: I left Syria in 1956, a few years before the Baath party became the government in 1963. I was always opposed to the Baathist ideology. I was always against the one-party state.

CNN: You left Syria after being imprisoned for membership of an opposition party in 1956, then you left Lebanon in 1982 after the Israeli invasion. Do you feel you have always been in exile?

A: I don’t only feel in exile because of these two departures. There are many other factors making me feel this way: Relationships with other people, my relationship with language, my relationship with the world. Love sometimes makes you feel you are in exile. Existentially, the feeling of permanence is always accompanied by a feeling of exile, of impermanence.

CNN: How has Syria changed since you left?

A: What’s strange is I feel it is I who has changed, not the country.

CNN: What are your memories of the Syria of your youth?

A: I remember the coast, the mountains, the beautiful girls for which Syria is famous. I miss swimming in the sea.

CNN: Will you ever go back to live in Syria?

A: I would like to go back, but I don’t think my desire will be fulfilled.

CNN: The Mosaic Rooms in London is currently running ‘A Tribute to Adonis’ and an exhibition of your artwork. What does this mean to you?

A: I’m very happy. There’s a lot of attention and a lot of sensitive appreciation.

CNN

Adonis: a life in writing

Adonis the greatest living poet of the Arab world, ushers me down a labyrinthine corridor in a stately building in Paris, near the Champs Elysées. The plush offices belong to a benefactor, a Syrian-born businessman funding the poet’s latest venture – a cultural journal in Arabic, which he edits. Fetching a bulky manuscript of the imminent third issue of the Other, Adonis hefts it excitedly on to a coffee table, listing the contributors “from west and east”, many of them of his grandchildren’s generation. He turned 82 this month. His eyes spark: “We want new talents with new ideas.”

A Syrian-born poet, critic and essayist, and a staunch secularist who sees himself as a “pagan prophet”, Adonis has been writing poetry for 70 years. He led a modernist revolution in the second half of the 20th century, exerting a seismic influence on Arabic poetry comparable to TS Eliot‘s in the anglophone world. Aged 17, he adopted the name of the Greek fertility god (pronounced Adon-ees, with the stress on the last syllable) to alert napping editors to his precocious talent and his pre-Islamic, pan-Mediterranean muses. Since the death of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish in 2008, it would be hard to argue for a poet of greater stature in a literary culture where poetry is the most prestigious form as well as being popular.

He moved to Paris in 1985, and was named a commander of France’s Order of Arts and Letters in 1997. Last year he was the first Arab writer to win the Goethe prize in Germany, and each autumn is credibly tipped for the Nobel in literature – the only Arab recipient of which to date was the Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz in 1988. Though Adonis was Ladbroke’s favourite in the year of the Arab spring, he does not begrudge the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer his laurels, having introduced him to audiences on a tour of Arab countries. When the uprisings began in Tunisia and Egypt last year, he wrote “little poems to express my joy and happiness”. Yet joy gave way to caution, and warnings of tragedy. “It’s the Arab youth that created this spring, and it’s the first time Arabs are not imitating the west – it’s extraordinary,” he says. “But despite this, it’s the Islamists and merchants and Americans who have picked the fruits of this revolutionary moment.” His reservations sparked impatience and were widely attacked: Sinan Antoon, an Iraqi poet, novelist and assistant professor at New York University, claimed that the Arab spring has “consigned Adonis, the self-proclaimed revolutionary, to irrelevance”.

There is, Adonis says, a “tendency for poets and painters in the Arab world to be politically engaged. There’s a lot to fight for: for human rights and the Palestinians; and against colonialism, Arab despotism and closed thinking among fundamentalists. I’m not against this engagement, or against them – but I’m not like them. A creator always has to be with what’s revolutionary, but he should never be like the revolutionaries. He can’t speak the same language or work in the same political environment.” He adds that he is “radically against the use of violence – I’m with Gandhi, not Guevara.”

Like VS Naipaul, a friend who has praised him as a “master of our times”, Adonis can be a contrarian, though he lacks Naipaul’s acidity and irrascibility. For critics, some of his pronouncements on the “extinction” of Arab culture, or the “Arab mind”, have an orientalist taint. Yet his translator Khaled Mattawa, an Arab American poet, sees it as measured iconoclasm: “He’s been unsparing against the deeply rooted forces of intolerance in Arab thought, but also celebratory of regenerative streaks in Arab culture.”

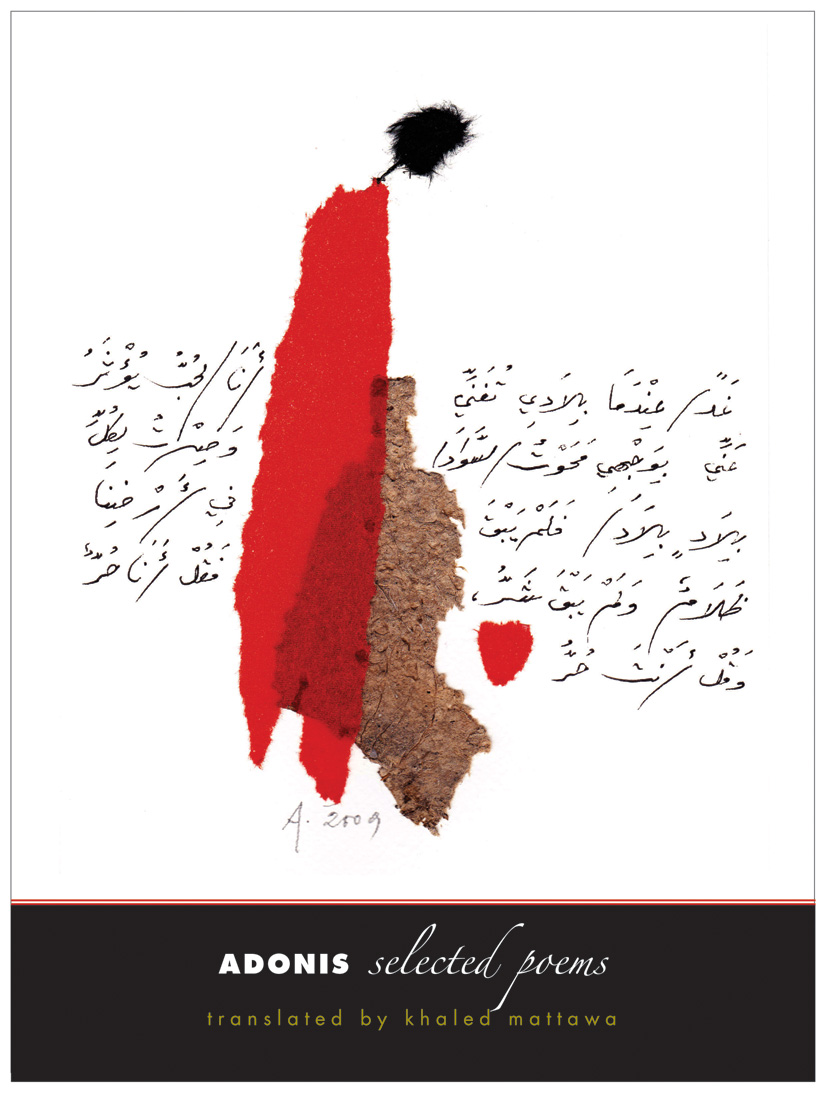

Although English translations of his poetry have lagged behind French, in the past decade there have been five collections: Mattawa’s Adonis: Selected Poems won the Saif Ghobash-Banipal prize for Arabic translation. Adonis will be coming to London for the award ceremony next month, and also to take part in a two-month celebration of his work, “A Tribute to Adonis”, at West London’s Mosaic Rooms starting on February 3, which includes an exhibition of the poet’s recent art works. He began making small collages using Arabic calligraphy 10 years ago, during a listless period of poet’s block, and friends suggested he exhibit them. “I found another way to express my relation to things, other than the word.” He uses parchments and rags, “bits and pieces of nothing, thrown away. I rarely use colour; I prefer ripped things,” adding fragments of his own poems, as well as classical Arabic poetry “as a homage”.

Last June, amid the bloody crackdown on the Syrian uprising, Adonis wrote an open letter to Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad in the Lebanese newspaper al-Safir – “as a citizen,” he stresses. Describing Syria as a brutal police state, he attacked the ruling Ba’ath party, called on the president to step down, and warned that “you cannot imprison an entire nation”. He was none the less taken to task for addressing a tyrant as an elected president, and criticising the “violent tendencies” of some of his opponents. “That’s why I said I’m not like the revolutionaries,” he says. “I’m with them, but I don’t speak the same language. They’re like school teachers telling you how to speak, and to repeat the same words. Whereas I left Syria in 1956 and I’ve been in conflict with it for more than 50 years. I’ve never met either Assad [Bashar or his father, Hafez]. I was among the first to criticise the Ba’ath party, because I’m against an ideology based on a singleness of ideas.

“What’s really absurd is that the Arab opposition to dictators refuses any critique; it’s a vicious circle. So someone who is against despotism in all its forms can’t be either with the regime or with those who call themselves its opponents. The opposition is a regime avant la lettre.” He adds: “In our tradition, unfortunately, everything is based on unity – the oneness of God, of politics, of the people. We can’t ever arrive at democracy with this mentality, because democracy is based on understanding the other as different. You can’t think you hold the truth, and that nobody else has it.”

His mother, aged 107, still lives in Syria. For 20 years after he left the country (when released from a year’s imprisonment for membership of an opposition party), he was unable to see her. From 1976, he visited each year until two years ago, when “friends said it might be dangerous”. But he is adamant that family circumstances have “never stopped me from saying what I think”. Of those who accuse him of tardiness or equivocation in condemning the Syrian regime, he says wearily: “I’ve written many articles – I have a book of them coming out that’s 200 pages long. These people don’t read.”

He lives on the outskirts of Paris, beyond la Défense, with his wife, Khalida Said, a literary critic. “For me she’s a great critic, one of the best. Sometimes we agree, sometimes we disagree.” They have two daughters: Arwad, who is director of the House of World Cultures in Paris; and Ninar, an artist who moves between Paris and Beirut. Adonis shows little sign of having just spent seven months in Lebanon convalescing from two major operations. Before that, he had announced his retirement from poetry. It was while writing a long poem against monotheism, “Concerto for Jerusalem”. “Jerusalem is a city of three monotheistic religions,” he says. “If there’s one God, it should be beautiful. Instead, it’s the most inhuman city in the world. I said I was stopping poetry as an act of defiance.” But alluding to his muses, he laughs: “The pre-monotheistic goddesses didn’t let me retire.”

He was born Ali Ahmad Said Esber in 1930, in Qassabin in western Syria, a “poor village isolated in the mountains”. His parents were farmers, and he had no early formal schooling. “I’d never seen a car, electricity or a telephone till I was 13. I always ask myself how I was transformed into this other person; it was almost miraculous.” His love of poetry was nurtured by his father, and at Qur’anic school. Aged 13, when he impressed the president of the newly established Syrian republic by reciting one of his own poems, his reward was a scholarship to the French lycée. He studied philosophy at Damascus university, and later did a doctorate in Lebanon.

During a year in Paris in 1960, he found his voice in the poem Mihyar of Damascus: His Song (1961), with echoes of Noah, Adam, Ulysses and Orpheus. While for him, poetry and religion are rivals, Sufi mysticism is a force for renewal. Sufism and Surrealism – the title of his 1995 book – are united in the idea, as he expressed it in a poem, that reality is “nothing but skin that crumbles as soon as you touch it”. He is also drawn to a mystical view that identity is not fixed: “A human being creates his identity in creating his oeuvre.” Yet Sufism is more profound than surrealism or existentialism, he says, “because it’s related to a revolutionary idea – that the other is me; that I am the other. If I travel towards myself, I must go through the other.”

This is no philosophical nicety. His family belonged to the Shia minority Alawites, and it is sometimes suggested that this gives him his sense of being apart. “It’s not being Alawite that gives me a sense of difference,” he objects, “but the present state of the Arab world. A man isn’t Protestant, Catholic, Sunni or Shia by birth; it’s through projects and pathways that men become Shia or Alawite. I never subscribed to that.” He joined the secular Syrian Social Nationalist party, opposed to the colonisation and partition of Syria, “partly to get out of concepts of minorities and majorities”. He was duly jailed during his military service in the mid-1950s. Since he quit the party in 1960, he has never belonged to another. “I was only 14 or 15 when I joined – a child. Later, I said I can’t be both poet and politically engaged. Ideology is against art.”

Beirut, where he fled with his wife into exile in 1956, was a “second birth”. He co-founded influential magazines, Shir (Poetry) and Mawaquif (Position), embracing colloquial Arabic and opposing both Arab nationalism and poetry as propaganda. TS Eliot was one of the first poets they interviewed, and Adonis collaborated on translations of The Waste Land, as well as on the works of Ezra Pound, Stephen Spender, Philip Larkin and Robert Lowell. He combined new sources with an encyclopaedic, “virgin” reading of Arabic classics. True creation, he says, is “always modern because it speaks to us – Ovid, Heraclitus, Homer, Dante. What’s not modern are the imitators. In classical Arabic poetry, you have to know how to distinguish between the greats and their imitators.”

His long poem This Is My Name (1970) was spurred by shock at the Arab defeat of 1967. The Book of Siege (1982) came out of the Lebanese civil war that began in 1975, and the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, which he lived through, before leaving for Paris. As he wrote in the opening lines: “The cities dissolve, and the earth is a cart loaded with dust. / Only poetry knows how to pair itself to this space.” The six-day war “was terrible, but I wasn’t conscious then of its tragic nature, as I was in 1982,” he says.

He had first welcomed the Iranian revolution of 1979, but swiftly rejected its reactionary turn. His book The Fixed and the Changing (1974) on a struggle between creativity and intolerance in the Arab world, identified an Arab malaise of “pastism”, which he defines now as seeing the past as the “source you must return to, despite the river running on with time. One has to break this circular time. You can’t have a revolution to go back to the past.”

As the Arab uprisings spread, Adonis said in a television interview that he could not take part in a revolution that emanated from the mosques. He was accused of siding with the regimes, and being out of touch with the dire circumstance of revolt. Asked whether he supports the peaceful protests, he spreads his arms as though pulling a concertina: “If you have a petition, I’ll sign it.” Does he worry that his words echo Arab dictators who pose as bulwarks against Islamists? “But with a difference,” he says. “I’m against the regimes of Ben Ali and Assad, and against the Islamist opposition, because I don’t want to fight one despotism for the sake of another … If we don’t separate religion from the state, and free women from Sharia law, we’ll just have more despots. Military dictatorship controls your mind. But religious dictatorship controls your mind and body.”

What of Islamist power through the ballot box? “In that case, democracy won’t be a criterion of progress, so the notion of democracy has to be rethought. Truth is not always on the side of democracy – what can you do?” He concedes that democracy, “with all its failings, is much less bad than dictatorship”. Rule by democratically elected Islamists would, “absolutely be better – but I’d be against it”.

With Syria teetering on civil war – and speaking before President al-Assad rejected Arab League calls to step down – Adonis was unequivocal that “the present regime absolutely has to go. The Ba’ath party has to go, and another regime to be put in place that’s secular, democratic and pluralist.” Yet he is against both armed uprising and foreign intervention. “Guns can’t resolve these problems. If everyone took up arms, there’d be civil war.” Outside military intervention has “destroyed Arab countries, from Iraq to Libya”. As for its humanitarian rationale, “it’s not true – it’s to colonise. If westerners really want to defend Arab human rights, they have to start by defending the rights of the Palestinians.”

Calls for intervention from within Arab countries “are wrong; it doesn’t make sense. How can you build the foundations of the state with the help of the same people who colonised these countries before?” At a talk this month in the House of Poetry in Paris, he held up a photograph published in al-Quds of some US soldiers in Iraq apparently desecrating the dead. “American soldiers pissed on Iraqi corpses,” he says indignantly. “So these are the same people they want to call in to liberate Arabs, and piss on the living?”

Yet within the west, he argues “there are many wests – of Rimbaud, Whitman and Eliot, and of Bush, Sarkozy and Cameron.” Explaining his view of Arab culture as extinct, he says: “What is civilisation? It’s the creation of something new, like a painting. A people that no longer creates becomes a consumer of the products of others. That’s what I mean by the Arabs being finished – not as a people, but as a creative presence.”

Adonis holds no hope that poetry can change society. To do that, “you have to change its structures – family, education, politics. That’s work art cannot do”. Yet he believes it can change the “relationship between things and words, so a new image of the world can be born.” Theorising about poetry is “like speaking about love. There are some things you can’t explain. The world is not created to be understood, but to be contemplated and questioned.”

GUARDIAN

![maxresdefault[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/maxresdefault12-300x168.jpg)

![f04da2db1122137cf9e232[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/f04da2db1122137cf9e2321-300x282.jpg)

![karagiozi2[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/karagiozi21-300x204.jpg)

![467341746[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/4673417461-300x200.jpg)

![Part-PAR-Par8128369-1-1-0[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Part-PAR-Par8128369-1-1-01-300x199.jpg)

![024_efi[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/024_efi1-244x300.jpg)

![Screen-Shot-2015-05-20-at-00.03.57[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Screen-Shot-2015-05-20-at-00.03.571-300x191.png)

![Karagkiozis[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Karagkiozis1-269x300.jpg)

![kantada%20ΟΛΟΙ[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/kantada-ΟΛΟΙ1-300x132.jpg)

![Dalianoudi_Karagiozis_9[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Dalianoudi_Karagiozis_91-300x197.jpg)

Recent Comments