Seferis Biography

Posted on Jan 21, 2015 |

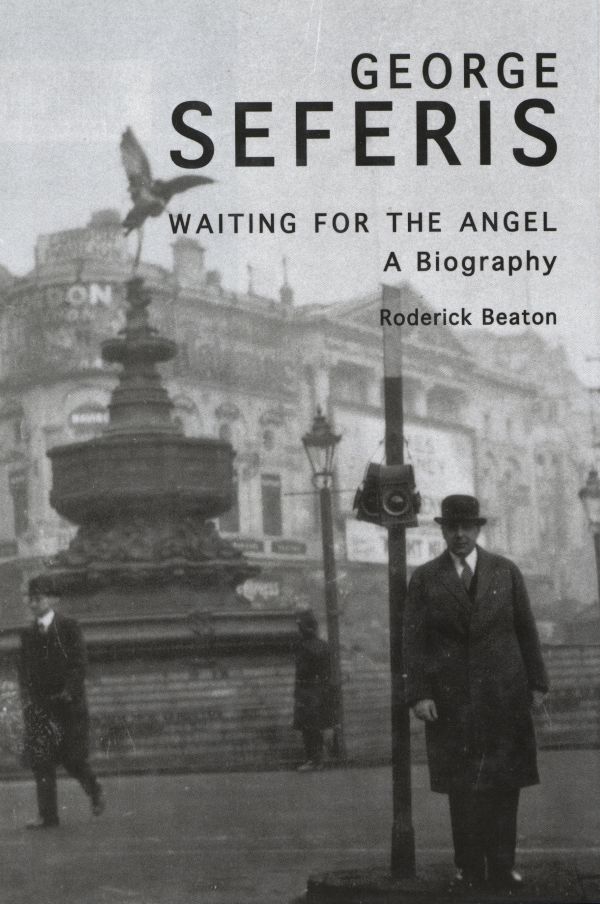

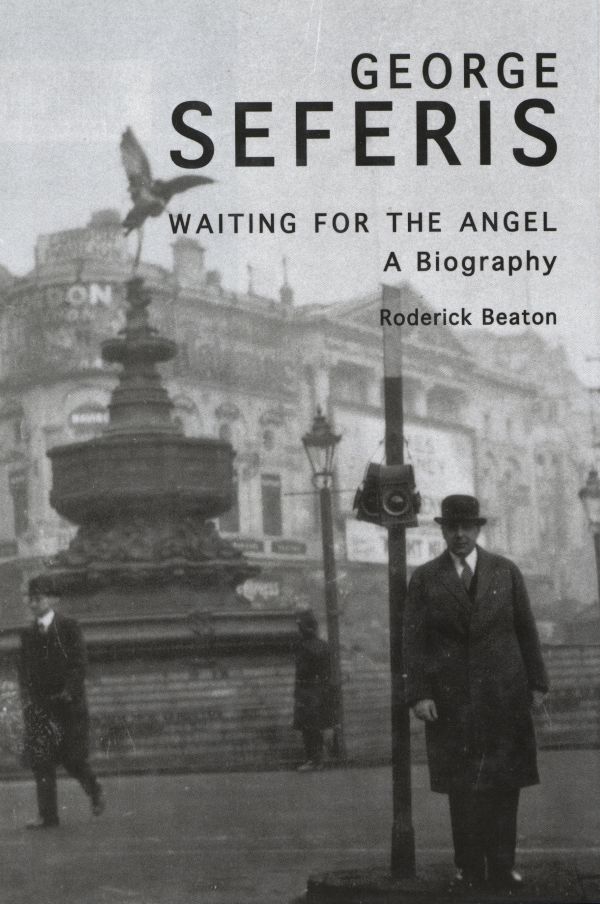

George Seferis: Waiting for the Angel – A Biography by Roderick Beaton

“Poet, essayist, diarist, novelist, and diplomat, George Seferis brought about a revolution in the way people viewed his native Greece. Acclaimed for his thought-provoking lyric poetry, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1963. At the same time, he rose in the diplomatic corps to the position of Ambassador to Britain. This biography of Seferis provides insights into his work, life, and country. Roderick Beaton, an acknowledged authority on modern Greek literature and culture, draws on previously unknown sources to tell Seferis’s story. He describes how Seferis occupied key diplomatic positions during periods of historic crisis before, during, and after World War II. He explores Seferis’s service as Ambassador to London at a time when Greece and Great Britain were disputing the future of Cyprus, noting that some of Seferis’s finest poetry was written about that troubled island. He analyses Seferis’s literary production and his impact on Lawrence Durrell, Henry Miller, and other British and American writers. Exploring the interplay between poet and diplomat, public and private, and poetry and politics in Seferis’s life and career, this book should interest anyone interested in 20th-century Greek literature, culture, or history.”

Available on Amazon

“Ο τελευταίος σταθμός”

“Έλληνες του Πνεύματος και της Τέχνης”

FOG

[…] moved into lodgings at 121 Boundaries Road, in Balham, a suburb of southwest London between Wandsworth and Tooting. They lodge with an irish family…Years later (writing to a friend, in English) George would remember them as ‘terribly ‘sentimental’ and ‘poetic'”. On a different occasion he recalled:

“There was a large dark tree in front of my window. I had gas lighting and kept warm with an open coal fire. I stayed up late, reading poets I couldn’t understand, or writing”

The house is a typical London suburban two-storey house, built around the beginning of the century, in red brick, on a corner plot.

[…] Among a group of photographs taken by the kitchen window, is one in which George looks soulful, sitting in a wicker chair. In another, he is standing holding the cat-to his mother he wrote that he talked English even to the cat-… {p. 61}

[…]

To Angelos, that October, George also vividly described is first experience of the legendary London ‘pea-souper’. Under the condition that would today be called ‘smog’, George felt that he and all the other inhabitants of the city were living in the depths of the sea; {p. 62}

[…] after George had left Paris and returned to Greece. A diary entry for August 1926, a year and a half after his return, reads:

“The most powerful passion I have, the passion to express myself, has been an unquenchable source of misery for me. It was this that made me unthinkingly injure the woman I loved”

[…]

Writing to his sister after it was over, George recalled the ‘superhuman effort’ of his first two years back in Greece: “How much you have to forget yourself, or alter your natural condition, so as keep hold of real contact at a distance”

[…]

The condition that George experienced during these two years was to find its most lyrical expression in retrospect, in poem 15 of Mythistorema (1935):

“Have mercy on those who wait with so much patience

lost among dark laurels beneath the heavy plane-trees

and those who all alone talk to wells and springs

and are drowned in the ripples of the voice.” {pp. 69-70}

[…]

At the same time George began systematically to read Homer’s Odyssey, in the French parallel-text prose version by Victor Berard. In Greek, he read for the first time the two masterpieces of prose that had been written in the vernacular (demotic) during the nineteeth century, but had been remained unknown until the twentieth. The ‘Woman of Zakynthos’ by Greece’s ‘national poet’ Dionysios Solomos, is a satire that draws on the tone and imagery of the biblical Apocalyspe; the historical Memoirs of General Makriyannis bear witness to the Greek war of independence in the 1820s and its aftermath. Both served George ever afterwards, not just as stylistic models, but (the latter especially) as the repository of a simple and profound moral conscience that he would always attribute to the Greek people. {p. 71}

[…]

In later life, both George and his sister were always reticent about their mother. […] George believed he could learn from the example of his mother’s life:

“….the most important thing isn’t to change our life, dreaming of another more interesting one, but to give voice to the life that we’ ve got, just as it was given to us: this hundrum, humble, human life, in which everything we could possibly ask for has to exist. It’s in this life that belongs to us, that no one can take away from us and is unique (since it belongs to no one else)…that we’ve got to learn to see the miracle.” {p. 72}

[…]

A week later he presented himself for the first time at the austere building with tall, neoclassical portals, just off Syntagma Square in the centre of Athens, that still houses part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. For the next two years, he would be assigned to the cryptography department. Today outside the building in the row pedestrianised Zalokosta Street, a bust of George Seferis surmounts a large plinth of rough-hewn marble. It is a much older man, in pullover and tie, who looks with pained sadness downwards past the pen held in his hand. Inside, a room was named after him in an official ceremony in May 2000. It is unlikely that the twenty-six-year-old George, ambitious as a writer and resentful of his new professional duties, would ever have imagined such a form of public recognition, here of all places. {p. 73}

[…]

Temperamentally very different from George, the young Katsimbalis was an ardent supporter of Venizelos, and remained an unashamed, life-long nationalist. He had twice carried these convictions to the point of action, serving as a volunteer, first on the Macedonian Front from May 1917 until the end of the first World War, and then in the Anatolian campaign, in which he rose to become captain of artillery. It is not entirely clear to what extent his subsequent disabilities were the result of wounds received in the fighting . But it was characteristic of George Katsimbalis’ larger-than-life personality that the ‘big stick’ (mangura) which was ever afterwards necessary for mobility, should soon have become a legendary symbol of his dominance over the Greek literary life from the 1930s to the 1950s. {p. 79}

George Katsimpalis, George Seferis and Patrick Lee Fermor

Sir Patrick Michael Leigh Fermor (11 February 1915 – 10 June 2011), also known as Paddy Fermor, was a British author, scholar and soldier who played a prominent role behind the lines in the Cretan resistance during during the Second World War. He was widely regarded as “Britain’s greatest living travel writer” during his lifetime, based on books such as A Time of Gifts (1977).

After many years together, Leigh Fermor was married in 1968 to the Honourable Joan Elizabeth Rayner. She accompanied him on many of his travels until her death in Kardamyli in June 2003, aged 91. They had no children. They lived part of the year in their house in an olive grove near Kardamyli in the Mani Penisnula, southern Peloponnese, and part of the year in Gloucestershire.

Leigh Fermor was knighted in the 2004 New Years Honours. In 2007, he said that, for the first time, he had decided to work using a typewriter, having written all his books longhand until then. The house at Kardamyli was featured in the 2013 film Before Midnight.

For the last few months of his life he suffered from a cancerous tumour, and in early June 2011 he underwent a tracheotomy in Greece. As death was close, he expressed a wish to die in England and he died there, aged 96, on 10 June 2011, the day after his return.

Desk in Fermor’s garden near Kardamyli, 2007.

“No matters what happens, no matter what should befall us, whether.. God will protect us or not, the question is this and only this: what will we have done? …What will have done with our freedom, with our love, with our suffering? It’s a question that will always press in on us, a cycle from which we will never be able to break out,…the question will be always there: What did you take? What did you give? {p. 102}

(Fragment of a dialogue with Stratis Thalassinos, 1933)

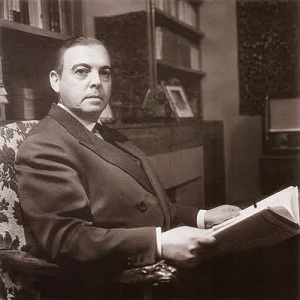

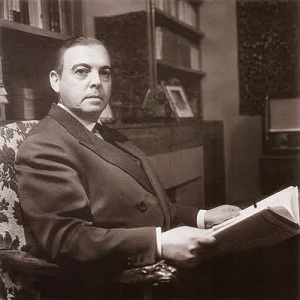

A photograph sent by George to Ioanna, in February 1932, shows him in a bowler hat and heavy, dark overcoat, buttoned up, standing up, standing stiffly beside a traffic light in Piccadilly Circus, London. Above him and behind him, out of his line of sight, soars the winged statue of Eros, which celebrates the fickle nature of sexual love, and is the real centrepiece of the photograph. As he commented to Ioanna: ‘I look awful but Eros has come out well.’ Clearly composed with a humorous, rueful eye, this photograph offers a striking visual counterpart to the earthbound, bereft state of ‘waiting for the angel’, with which , not long before this, the poem ‘Erotikos Logos’ had ended. A week after sending these photographs to Ioanna, George wrote to Katsimbalis, echoing the poem’s closing words: “The world is simple-only you have just finished a poem. {p. 102}

George Seferis in London 1924.

[…]

To Theotokas he confined that

if ever I had the chance to serve my country, seriously and to some purpose, I’d be ready todo my utmost, But before that could happen I would have a) to believe in the people who make things happen, and b) to feel that I really had something to offer. {p. 103}

Ο Γιώργος Σεφέρης με το συγγραφέα-δοκιμιογράφο Γιώργο Θεοτοκά, έναν από τους κύριους εκπροσώπους της Γενιάς του 30. Η φωτογραφία, όπως εμφανώς δηλώνεται, έχει τραβηχθεί στην Αθήνα (στα Προπύλαια του Πανεπιστημίου) το 1941 από πλανόδιο φωτογράφο. Ο Θεοτοκάς φορά στρατιωτική στολή, γιατί έχει κληθεί να υπηρετήσει στο στρατό λόγω του πολέμου.

[…]

But now, in the second half of 1931, newly arrived in London, George had other preoccupations. At the end of September, he moved into a two-room furnished flat in Hampstead, at 8 Antrim Grove, NW3. […] It is a leafy part of London, socially a considerable step up from Balham, where he had stayed on his first visit, seven years before. The other side of Antrim Grove has been rebuilt since the 1960s; Number 8 looks much as it must have done then: a demure, semi-detached house with bow windows to the front and a tiny front garden, almost hidden behind the traditional English privet hedges. George’s rooms were probably on the attic floor. {p. 103}

[…]

Many years later, George would write to Katsimbalis that it had been ‘under that large dark tree’ opposite his sitting-room window that Stratis Thalassinos had been born. […] ‘Mr Thalassinos’ is disposed to ‘write sociological observations about the place in which he finds himself’:

“English windows…have no shutters. So an Englishman who lives on the ground floor can never permitted hiself to think of having a naked woman with him. They must do their love-making under the table” {p. 104}

[…]

Something else that probably encouraged George to persevere with this alternative version of himself (Mr Stratis Thalassinos) was his friendship, which began at this time, with a real seafarer who was also a poet. This was the twenty-five-year-old Dimitris Antoniou (D.I. Antoniou, as he signed his poems; ‘Tonio’ to his friends). George had encountered him once before in Athens, at the house of the poet Palamas. Now serving as navigation officer on a long-distance cargo ship, Antoniou turned up at the door of George’s office at 131 Gower Street, one foggy winter afternoon early in December.

Although apparently a man of few words, Antoniou impressed George deeply on that occasion with his talk of life at sea. This young ship’s officer ‘carried more books with him than clothes’, his cabin aboard ship was piled high with empty cigarette packets: the manuscripts of the poems that before long he would publish with the encouragement of George and Katsimbalis. Henry Miller’s portrait of Antoniou, a few years later, well captures the aura with which the two literary Georges invested their ‘seafaring friend’:

” I envied him the islands he was always stopping off at…I like the idea of being alone in the little house above the deck, steering the ship over its perilous course. To be aware of the weather, to be in it, battling with it, meant everything to me. In Antoniou’s countenance there were always traces of the weather…I like men who have the weather in their blood.”

A lifelong bachelor, Antoniou seems to have dedicated his life t the sea and to poetry. He came from the Dodecanese, which means that as this time he may have been an Italian subject. {p. 105-016}

∼Άτιτλο∼

Άνθισα γύρω μου στη θάλασσα

άνθη – πουλιά που ζήσανε

στο εφήμερο κλίμα της νύχτας εκείνης.

Bρήκα τις κλωστές σαν ξημέρωνε,

αυτές που ζωντάνευαν τους τεχνητούς κύκνους μου,

σαν νεύρα με τη σάρκα

στην πλασματική τους ύπαρξη.

H κατασκευή τούτη που αρνήθηκες

με το φως της ημέρας

τον εαυτό της τόσο

τον εαυτό μου τότε που κυβερνούσε ένα καράβι

άσπρο κι αυτό σαν τα φανταστικά πουλιά

κείνη τη νύχτα που μου γύρεψες.

~Ω, πες μου αν δεν πιστεύεις~

Ω, πες μου αν δεν πιστεύεις ακόμη τα φαντάσματα!

τ’ άλογα που έχουν φτερά για παραμυθένιους τόπους,

τις μάγισσες με βότανα για το θάνατο και την αγάπη

και το ανθρώπινο πλάσμα το απλό που μας παραδώσαν οι καιροί·

τα μαλλιά του ήταν ο ήλιος για το σκοτεινό μας πύργο.

Mα τι λέω! Eσύ δεν είσαι ξανθή και τώρα

όταν σε κοιτάζω είσαι η νύχτα μου

έτσι για να σου πω απόψε:

Eδώ ‘μαι, αφού το θέλησες

όλος για να υπάρχω μ’ εσένα·

δες αυτό το χέρι κρατάει

στον αγώνα του τη μοίρα

τα βουνά μετατοπίζει

κι άστρα παιγνίδια στα χέρια σου απιθώνει…

Από τα Ποιήματα, Eρμής 1998

Βιογραφικό Σημείωμα

Δ.Ι. ΑΝΤΩΝΙΟΥ (1906-1994)

Ο Δημήτριος Αντωνίου γεννήθηκε στην Μπέιρα της Μοζαμβίκης και καταγόταν από μεγάλη ναυτιλιακή οικογένεια της Κάσου. Πέρασε τα πρώτα παιδικά του χρόνια στη γενέτειρά του και στο Σουέζ και ολοκλήρωσε τις εγκύκλιες σπουδές του στην Αθήνα, όπου εγκαταστάθηκε με την οικογένειά του το 1912. Φοίτησε στη Φιλοσοφική Σχολή του Πανεπιστημίου Αθηνών και ασχολήθηκε παράλληλα με την εκμάθηση ξένων γλωσσών και ερασιτεχνικά με την ορυκτολογία, τη βοτανική, την εντομολογία, τη ζωολογία, τη μουσική. Από το 1928 ακολούθησε στρατιωτική καριέρα στην εμπορική ναυτιλία και έφτασε ως το βαθμό του πλοιάρχου. Συνταξιοδοτήθηκε το 1968. Κατά τη διάρκεια του ελληνογερμανικού πολέμου υπηρέτησε ως έφεδρος αξιωματικός στο αντιτορπιλικό Κείος. Νέος μπήκε στον κύκλο του Παλαμά και γνωρίστηκε με τους Κωνσταντίνο Τσάτσο, Γιώργο Σεφέρη, Οδυσσέα Ελύτη και τους άλλους λογοτέχνες της λεγόμενης γενιάς του Τριάντα, με τους οποίους συμπορεύτηκε στην ανανέωση του ελληνικού ποιητικού λόγου. Στα γράμματα πρωτοεμφανίστηκε το 1936 από τις σελίδες των Νέων Γραμμάτων με τη δημοσίευση ποιημάτων που κρίθηκαν ευνοϊκά από το Γιώργο Σεφέρη. Εξέδωσε τρεις ποιητικές συλλογές (Ποιήματα, Ινδίες [Β΄ Κρατικό Βραβείο Ποίησης – 1967], Χάι-Κάι και Τάνκα [Α΄ Κρατικό Βραβείο Ποίησης – 1972]), ενώ πολλά έργα του (ποιήματα, λογοτεχνικά δοκίμια, μεταφράσεις) βρίσκονται δημοσιευμένα σε εφημερίδες και περιοδικά. Πηγή: Εθνικό Κέντρο Βιβλίου

Recent Comments