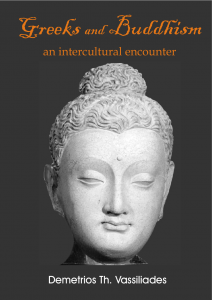

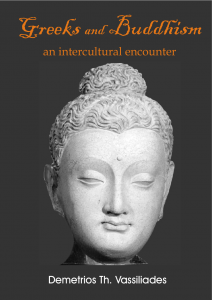

Greeks and Buddhism: An Intercultural Encounter

Posted on Jan 17, 2017 |

Book Description

This book examines the inter-cultural contacts that took place between Greeks and Buddhism over the course of approximately two thousand and five hundred years and played an extremely prominent and dynamic role in consolidation of the ecumenical spirit in the Buddhist and European thought.

It is based on the author’s previous essays, enriched and expanded with recent data derived from historical records, popular beliefs and traveling impressions. It includes the early historical contacts from the time of the Buddha up to the rise of the Graeco-Buddhist art, the impact of Buddhism on the Hellenistic Middle East and the formation of the Christian monasticism, and the works of Lafcadio Hearn, Marco Pallis and Nikos Kazantzakis who made the Japanese, the Tibetan-Indian and the Chinese Buddhism known to the Western world.

Its objective is to highlight the way the ecumenical religions of Buddhism and Christianity were formed upon drawing timeless values from the rich Greek and Indian traditions. On this basis, we hope that the book will be a useful instrument to scholars and students of the world religion and civilization.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface

Abbreviations

CHAPTER 1

Historical Contacts & Influences

The Buddha and the Greeks

Alexander, Megasthenes and the Indian religions

Aśoka and the Expansion of Buddhism

Menander and the Adoption of Buddhism

Gandhāra and the Rise of Graeco-Buddhist Art

Philosophical Influences and Parallelisms

References & Bibliography

Illustrations

CHAPTER 2

Buddhism & Christianity

Comparative Attempts

The Theory that Jesus Christ Studied Buddhism in India

Buddhism and Gnosticism

Early Historical Contacts

Common Practices in Buddhist and Christian Traditions

Objections and Conclusions

References & Bibliography

Illustrations

CHAPTER 3

Modern Greeks & Buddhism

I. Lafcadio Hearn & Buddhism

Hellenic Impact on Japanese Buddhism

Lafcadio Hearn ‒ Introduction of Buddhism in Japan

Lafcadio Hearn and Buddhism ‒ Sources and Influences

Buddhist Philosophy in the Light of Lafcadio Hearn

Concluding Remarks

References & Bibliography

Illustrations

II. Marco Pallis and Buddhism

Early Life and Musical Career

Absorbing the Spirit of Tibet by Direct Experience

Pallis’ Writings on Tibetan Buddhism

References & Bibliography

Illustrations

III. Nikos Kazantzakis and Buddhism

References & Bibliography

Illustrations

APPENDIX A

International Buddhist Conclave 2014 ‒ Visit to

Holy Sites of Buddhism

References & Bibliography

Illustrations

The Apollonian Smile

About the Author

Index of Proper Names

Contact Info:

Athens Center for Indian & Indo-Greek Studies

15 Nikolaou Florou str.

Athens 11524

Tel. 0030-6977874652

Contact Email:

The Indo-Greeks: The First Western Buddhists

![GBAMap[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/GBAMap1-177x300.jpg)

GRECO BUDDHISM

Greco-Buddhism, sometimes spelled Græco-Buddhism, is the cultural syncretism between the culture of Classical Greece and Buddhism, which developed over a period of close to 800 years in Central Asia in the area corresponding to modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, between the 4th century BC and the 5th century AD. Greco-Buddhism influenced the artistic (and, possibly, conceptual) development of Buddhism, and in particular Mahayana Buddhism, before it was adopted by Central and Northeastern Asia from the 1st century AD, ultimately spreading to China, Korea and Japan.

History

General area of Greco-Buddhism, and boundaries of the Kushan empire at its greatest extent around 150 AD.

The interaction between Hellenistic Greece and Buddhism started when Alexander the Great conquered Asia Minor and Central Asia in 334 BC, going as far as the Indus, thus establishing direct contact with India, the birthplace of Buddhism.

Alexander founded several cities in his new territories in the areas of the Oxus and Bactria, and Greek settlements further extended to the Khyber Pass, Gandhara (see Taxila) and the Punjab. These regions correspond to a unique geographical passageway between the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush mountains, through which most of the interaction between India and Central Asia took place, generating intense cultural exchange and trade.

Following Alexander’s death on June 10, 323 BC, his Diadochi (generals) founded their own kingdoms in Asia Minor and Central Asia. General Seleucus set up the Seleucid Kingdom, which extended as far as India. Later, the Eastern part of the Seleucid Kingdom broke away to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (3rd–2nd century BC), followed by the Indo-Greek Kingdom (2nd–1st century BC), and later still by the Kushan Empire (1st–3rd century AD).

The interaction of Greek and Buddhist cultures operated over several centuries until it ended in the 5th century AD with the invasions of the White Huns, and later the expansion of Islam.

Artistic influences

Numerous works of Greco-Buddhist art display the intermixing of Greek and Buddhist influences, around such creation centers as Gandhara. The subject matter of Gandharan art was definitely Buddhist, while most motifs were of Western Asiatic or Hellenistic origin.

The anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha

Many of the stylistic elements in the representations of the Buddha point to Greek influence: the Greco-Roman toga-like wavy robe covering both shoulders (more exactly, its lighter version, the Greek himation), the contrapposto stance of the upright figures (see: 1st–2nd century Gandhara standing Buddhas) the stylicized Mediterranean curly hair and top-knot apparently derived from the style of the Belvedere Apollo(330 BC), and the measured quality of the faces, all rendered with strong artistic realism (See: Greek art). A large quantity of sculptures combining Buddhist and purely Hellenistic styles and iconography were excavated at the Gandharan site of Hadda.

Greek artists were most probably the authors of these early representations of the Buddha, in particular the standing statues, which display “a realistic treatment of the folds and on some even a hint of modelled volume that characterizes the best Greek work. This is Classical or Hellenistic Greek, not archaizing Greek transmitted by Persia or Bactria, nor distinctively Roman” (Boardman).

The Greek stylistic influence on the representation of the Buddha, through its idealistic realism, also permitted a very accessible, understandable and attractive visualization of the ultimate state of enlightenment described by Buddhism, allowing it reach a wider audience: “One of the distinguishing features of the Gandharan school of art that emerged in north-west India is that it has been clearly influenced by the naturalism of the Classical Greek style. Thus, while these images still convey the inner peace that results from putting the Buddha’s doctrine into practice, they also give us an impression of people who walked and talked, etc. and slept much as we do. I feel this is very important. These figures are inspiring because they do not only depict the goal, but also the sense that people like us can achieve it if we try” (The Dalai Lama, foreword to “Echoes of Alexander the Great”, 2000).

During the following centuries, this anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha defined the canon of Buddhist art, but progressively evolved to incorporate more Indian and Asian elements.

A Hellenized Buddhist pantheon

Several other Buddhist deities may have been influenced by Greek gods. For example, Heracles with a lion-skin (who also happens to be the protector deity of Demetrius I) “served as an artistic model for Vajrapani, a protector of the Buddha” (Foltz, “Religions and the Silk Road”). In Japan, this expression further translated into the wrath-filled and muscular Niō guardian gods of the Buddha, standing today at the entrance of many Buddhist temples.

According to Katsumi Tanabe, professor at Chuo University, Japan (in “Alexander the Great.East-West cultural contact from Greece to Japan”), besides Vajrapani, Greek influence also appears in several other gods of the Mahayana pantheon, such as the Japanese Wind God Fujin inspired from the Greek Boreas through the Greco-Buddhist Wardo, or the mother deity Hariti (Kariteimo and Kishibojin (in Japan) inspired by Tyche.

In addition, forms such as garland-bearing cherubs, vine scrolls, and such semi-human creatures as the centaur and triton, are part of the repertory of Hellenistic art introduced by Greco-Roman artists in the service of the Kushan court.

Religious interactions

The length of the Greek presence in Central Asia and northern India provided opportunities for interaction, not only on the artistic, but also on the religious plane.

The Greek presence in Bactria (332 to 125 BC)

When Alexander conquered the Bactrian and Gandharan regions, these areas may already have been under Buddhist influence.

According to a legend preserved in Pali, the language of the Theravada canon, two merchant brothers from Bactria, named Tapassu and Bhallika, visited the Buddha and became his disciples. They then returned to Bactria and built temples to the Buddha (Foltz).

Alexander established in this same area several cities (Ai-Khanoum, Begram) and an administration that were to last more than two centuries under the Seleucids and the Greco-Bactrians, all the time in direct contact with Indian territory. From 180 BC, the Greco-Bactrians were further to expand into India, where they established the Indo-Greek kingdom.

In 125 BC, the northern Indo-European Yuezhi nomads (the future Kushans, promoters of the Mahayana faith) took control of the Bactrian territory, and displaced the remaining Greco-Bactrians to the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent. The Yuezhi underwent a process of Hellenization for more than a century, as exemplified by their coins and their adoption of the Greek alphabet.

The Mauryan empire (322-–183 BC)

The Indian emperor Chandragupta, founder of the Mauryan dynasty, re-conquered around 322 BC the northwest Indian territory that had been lost to Alexander the Great. However, contacts were kept with his Greek neighbours in the Seleucid Empire, Chandragupta received the daughter of the Seleucid king Seleucus I after a peace treaty, and several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes, resided at the Mauryan court.

Chandragupta’s son Bindusara also had a Greek ambassador at his court, named Deimachus (Strabo 1–70), and is known in Greek records for having requested a philosopher (a sophist) to the Seleucid king Antiochus I Soter (Athenaeus, “Deipnosophistae”).

Chandragupta’s grandson Asoka converted to the Buddhist faith and became a great proselytizer in the line of the traditional Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism, insisting on non-violence to humans and animals (ahimsa), and general precepts regulating the life of lay people.

According to the Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek, he sent Buddhist emissaries to the Greek lands in Asia and as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts name each of the rulers of the Hellenic world at the time.

Ashoka also claims he converted to Buddhism Greek populations within his realm: “Here in the king’s domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods’ instructions in Dhamma.” Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika)

Finally, some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as the famous Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources (the Mahavamsa, XII) as leading Greek Buddhist monks, active in Buddhist proselytism.

The Indo-Greek kingdom and Buddhism (180-–1 BC)

The Greco-Bactrians conquered northern India from 180 BC, whence they are known as the Indo-Greeks. They controlled various areas of the northern Indian territory until 1 BC.

Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greek kings, and it has been suggested that their invasion of India was intended to protect the Buddhist faith from the religious persecutions of the new Indian dynasty of the Sungas (185–73 BC) which had overthrown the Mauryans.

Coinage

The coins of the Indo-Greek king Menander (reigned 160 to 135 BC), found from Afghanistan to central India, bear the inscription “Saviour King Menander” in Greek on the front. Several Indo-Greek kings after Menander, such as Zoilos I, Strato I, Heliokles II, Theophilos, Peukolaos, Menander II and Archebios display on their coins the title of “Maharajasa Dharmika” (lit. “King of the Dharma”) in the Prakrit language and in the Kharoshthi script.

Some of the coins of Menander I and Menander II incorporate the Buddhist symbol of the eight-spoked wheel, associated with the Greek symbols of victory, either the palm of victory, or the victory wreath handed over by the goddess Nike.

The ubiquitous symbol of the elephant in Indo-Greek coinage may also have been associated with Buddhism, as suggested by the parallel between coins of Antialcidas and Menander II, where the elephant in the coins of Antialcidas holds the same relationship to Zeus and Nike as the Buddhist wheel on the coins of Menander II. When the zoroastrian Indo-Parthians invaded northern India in the 1st century AD, they adopted a large part of the symbolism of Indo-Greek coinage, but refrained from ever using the elephant, suggesting that its meaning was not merely geographical.

Finally, after the reign of Menander I, several Indo-Greek rulers, such as Amyntas, King Nicias, Peukolaos, Hermaeus, Hippostratos and Menander II, depicted themselves or their Greek deities forming with the right hand a benediction gesture identical to the Buddhist vitarka mudra (thumb and index joined together, with other fingers extended), which in Buddhism signifies the transmission of Buddha’s teaching.

Cities

According to Ptolemy, Greek cities were founded by the Greco-Bactrians in northern Pakistan. Menander established his capital in Sagala, today’s Sialkot in Punjab, one of the centers of the blossoming Buddhist culture (Milinda Panha, Chap. I). A large Greek city built by Demetrius and rebuilt by Menander has been excavated at the archeological site of Sirkap near Taxila, where Buddhist stupas were standing side-by-side with Hindu and Greek temples, indicating religious tolerance and syncretism.

Scriptures

Evidence of direct religious interaction between Greek and Buddhist thought during the period include the Milinda Panha, a Buddhist discourse in the platonic style, held between king Menander and the Buddhist monk Nagasena.

Also the Mahavamsa (Chap. XXIX) records that during Menander’s reign, “a Greek Buddhist head monk” named Mahadharmaraksita led 30,000 Buddhist monks from “the Greek city of Alexander-of-the-Caucasus” (around 150km north of today’s Kabul in Afghanistan), to Sri Lanka for the dedication of a stupa, indicating that Buddhism flourished in Menander’s territory and that Greeks took a very active part in it.

Several Buddhist dedications by Greeks in India are recorded, such as that of the Greek meridarch (civil governor of a province) Theodorus, describing in Kharoshthi how he enshrined relics of the Buddha during the reign of Menander or his successor (Tarn, p.388).

Finally, Buddhist tradition recognizes Menander as one of the great benefactors of the faith, together with Asoka and Kanishka.

Buddhist manuscripts in cursive Greek have been found in Afghanistan, praising various Buddhas and including mentions of the Mahayana Lokesvara-raja Buddha (λωγοασφαροραζοβοδδο). These manuscripts have been dated later than the 2nd century AD. (Nicholas Sims-Williams, “A Bactrian Buddhist Manuscript”).

The Mahayana movement probably began around the 1st century BC in northwestern India, at the time and place of these interactions. According to most scholars, the main sutras of Mahayana were written after 100 BC, when sectarian conflicts arose among Nikaya Buddhist sects regarding the humanity or super-humanity of the Buddha and questions of metaphysical essentialism, on which Greek thought may have had some influence: “It may have been a Greek-influenced and Greek-carried form of Buddhism that passed north and east along the Silk Road” (McEvilly, “The shape of ancient thought”).

The Kushan empire (1st–3rd century AD)

The Kushans, one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi confederation settled in Bactria since around 125 BC, invaded the northern parts of Pakistan and India from around 1 AD.

By that time they had already been in contact with Greek culture and the Indo-Greek kingdoms for more than a century. They used the Greek script to write their language. The absorption of Greek historical and mythological culture is suggested by Kushan sculptures representing Dyonisiac scenes or even the story of the Trojan horse (See: Kushan Trojan horse and it is probable that Greek communities remained under Kushan rule.

The Kushan king Kanishka, who honored Zoroastrian, Greek and Brahmanic deities as well as the Buddha and was famous for his religious syncretism, convened the Fourth Buddhist Council around 100 AD in Kashmir, which marked the official recognition of the pantheistic Mahayana Buddhism and its scission with Nikaya Buddhism. Some of Kanishka’s coins bear the earliest representations of the Buddha on a coin (around 120 AD), in Hellenistic style and with the word “Boddo” in Greek script .

Kanishka also had the original Gandhari vernacular, or Prakrit, Mahayana Buddhist texts translated into the high literary language of Sanskrit, “a turning point in the evolution of the Buddhist literary canon” (Foltz, Religions on the Silk Road)

The “Kanishka casket”, dated to the first year of Kanishka’s reign in 127 AD, was signed by a Greek artist named Agesilas, who oversaw work at Kanishka’s stupas (caitya), confirming the direct involvement of Greeks with Buddhist realizations at such a late date.

The new syncretic form of Buddhism expanded fully into Eastern Asia soon after these events. The Kushan monk Lokaksema visited the Han Chinese court at Loyang in 178 AD, and worked there for ten years to make the first known translations of Mahayana texts into Chinese. The new faith later spread into Korea and Japan, and was itself at the origin of Zen.

Greco-Buddhism and the rise of the Mahayana

The geographical, cultural and historical context of the rise of Mahayana Buddhism during the 1st century BC in northwestern India, all point to intense multi-cultural influences: “Key formative influences on the early development of the Mahayana and Pure Land movements, which became so much part of East Asian civilization, are to be sought in Buddhism’s earlier encounters along the Silk Road” (Foltz, Religions on the Silk Road).

Conceptual influences

Mahayana is an inclusive faith characterized by the adoption of new texts, in addition to the traditional Pali canon, and a shift in the understanding of Buddhism. It goes beyond the traditional Theravada ideal of the release from suffering (dukkha) and personal enlightenment of the arhats, to elevate the Buddha to a God-like status, and to create a pantheon of quasi-divine Bodhisattvas devoting themselves to personal excellence, ultimate knowledge and the salvation of humanity. These concepts, together with the sophisticated philosophical system of the Mahayana faith, may have been influenced by the interaction of Greek and Buddhist thought:

The Buddha as an idealized man-god

The Buddha was elevated to a man-god status, represented in idealized human form: “One might regard the classical influence as including the general idea of representing a man-god in this purely human form, which was of course well familiar in the West, and it is very likely that the example of westerners’ treatment of their gods was indeed an important factor in the innovation… The Buddha, the man-god, is in many ways far more like a Greek god than any other eastern deity, no less for the narrative cycle of his story and appearance of his standing figure than for his humanity” (Boardman, “The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity” ).

The supra-mundane understanding of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas may have been a consequence of the Greek’s tendency to deify their rulers in the wake of Alexander’s reign: “The god- king concept brought by Alexander (…) may have fed into the developing bodhisattva concept, which involved the portrayal of the Buddha in Gandharan art with the face of the sun god, Apollo” (McEvilly, “The Shape of Ancient Thought”).

The Bodhisattva as a Universal ideal of excellence

Greek influence has been suggested (Etienne Lamotte, cited in Williams) in the definition of the Bodhisattva ideal in the oldest Mahayana text, the “Perfection of Wisdom” or prajñā pāramitā literature, between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD in Northwestern India. These texts in particular redefine Buddhism around the universal Bodhisattva ideal, and its six central virtues of generosity, morality, patience, effort, meditation and, first and foremost, wisdom.

These qualities are reminiscent the Greek Stoicist philosophy, which may also have influenced the understanding of each individual as having the potential to reach excellence (Concept of Universal Buddha nature) and as being equally worthy of compassion (Compassion for all or “Karuna”, related to the Greek Universal loving kindness, “Philanthropia”). The Stoics had a “conviction in the essential equality of all humankind (…), which did not provide for superior or inferior, dominant and subordinate relations between states. From the ideal of equality there followed the Stoics’ emphasis on virtue, conscience, duty, and absolute personal integrity” (Bentley, “Old World Encounters”).

Philosophical influences

The close association between Greeks and Buddhism probably led to exchanges on the philosophical plane as well. Many of the early Mahayana theories of reality and knowledge can be related to Greek philosophical schools of thought. Mahayana Buddhism has been described as the “form of Buddhism which (regardless of how Hinduized its later forms became) seems to have originated in the Greco-Buddhist communities of India, through a conflation of the Greek Democritean-Sophistic-Skeptical tradition with the rudimentary and unformalized empirical and skeptical elements already present in early Buddhism” (McEvilly, “The Shape of Ancient Thought”).

In the Prajnaparamita, the rejection of the reality of passing phenomena as “empty, false and fleeting” can also be found in Greek Pyrrhonism.

The distinction between conditioned and unconditioned being, and the denial of the reality of everyday experience in favour of an “unchanging and absolute ground of Being” is at the center of Platonism as well as Nagarjuna’s Madhyamika thought.

The perception of ultimate reality was, for the Cynics as well as for the Madyamikas and Zen teachers after them, only accessible through a non-conceptual and non-verbal approach (Greek “Phronesis”), which alone allowed to get rid of ordinary conceptions.

The mental attitude of equanimity and dispassionate outlook in front of events was also characteristic of the Cynics and Stoics, who called it “Apatheia”.

Greco-Persian cosmological influences

One of the most popular themes of Greco-Buddhist art, the future Buddha Maitreya, has often been linked to the Iranian saviour figure Mitra, itself adopted as a Greek syncretic cult under the name Mithras. Maitreya pertains to the traditions of the “Second coming” of a Messiah and “echoes the qualities of the Zoroastrian Saoshyant and the Christian Messiah” (Foltz). The Buddha Amitabha (literally meaning “Infinite radiance”) with his Western paradisiacal “Pure Land” “seems to be understood as the Iranian god of light, equated with the sun” (Foltz). The very notion of paradise is a Persian invention (Old Persian: “Para Daisa”), which was probably relayed by the Greeks.

However, Mitra was also a solar diety of the Hindu Vedic Pantheon and Hindus have the notion of swarg, or the heavens.

Gandharan proselytism

Buddhist monks from the region of Gandhara, where Greco-Buddhism was most influential, played a key role in the development and the transmission of Buddhist ideas in the direction of northern Asia.

Kushan monks, such as Lokaksema (c. 178 AD), travelled to the Chinese capital of Loyang, where they became the first translators of Mahayana Buddhist scriptures into Chinese. Central Asian and East Asian Buddhist monks appear to have maintained strong exchanges until around the 10th century, as indicated by frescos from the Tarim Basin.

Two half-brothers from Gandhara, Asanga and Vasubandhu (4th century), created the Yogacara or “Mind-only” school of Mahayana Buddhism, which through one of its major texts, the Lankavatara Sutra, became a founding block of Mahayana, and particularly Zen, philosophy.

In 485 AD, according to the Chinese historic treatise Liang Shu, five monks from Gandhara travelled to the country of Fusang (“The country of the extreme East” beyond the sea, probably eastern Japan, although some historians suggest the American Continent), where they introduced Buddhism:

“Fusang is located to the east of China, 20,000 li (1,500 kilometers) east of the state of Da Han (itself east of the state of Wa in modern Kyushu, Japan). (…) In former times, the people of Fusang knew nothing of the Buddhist religion, but in the second year of Da Ming of the Song dynasty (485 AD), five monks from Kipin (Kabul region of Gandhara) travelled by ship to Fusang. They propagated Buddhist doctrine, circulated scriptures and drawings, and advised the people to relinquish worldly attachments. As a results the customs of Fusang changed”

Bodhidharma, the founder of Zen, is described as a Central Asian Buddhist monk in the first Chinese references to him (Yan Xuan-Zhi, 547 AD), although later traditions describe him as coming from South India.

See also: Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

Intellectual influences in Asia

Through art and religion, the influence of Greco-Buddhism on the cultural make-up of Northern Asian countries, especially Korea and Japan, may have extended further into the intellectual area.

At the same time as Greco-Buddhist art and Mahayana schools of thought such as Zen were transmitted to northern Asia, central concepts of Hellenic culture such as virtue, excellence or quality may have been adopted by the cultures of Korea and Japan after a long diffusion among the Hellenized cities of Central Asia, to become a key part of their warrior and work ethics.

Greco-Buddhism and the West

In the direction of the West, the Greco-Buddhist syncretism may also have had some formative influence on the religions of the Mediterranean Basin.

Exchanges

Intense westward physical exchange at that time along the Silk Road is confirmed by the Roman craze for silk from the 1st century BC to the point that the Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds. This is attested by at least three significant authors:

Strabo (64/ 63 BC–c. 24 AD).

Seneca the Younger (c. 3 BC–65 AD).

Pliny the Elder (23-–79 AD).

The aforementioned Strabo and Plutarch (c. 45–-125 AD) wrote about king Menander, confirming that information was circulating throughout the Hellenistic world.

Religious influences

Although the philosophical systems of Buddhism and Christianity have evolved in rather different ways, the moral precepts advocated by Buddhism from the time of Ashoka through his edicts do have a very strong similarity with the Christian moral precepts developed more than two centuries later: respect for life, respect for the weak, rejection of violence, pardon to sinners, tolerance.

These similarities may indicate the propagation of Buddhist ideals into the Western World, the Greeks acting as intermediaries and religious syncretists: “Scholars have often considered the possibility that Buddhism influenced the early development of Christianity. They have drawn attention to many parallels concerning the births, lives, doctrines, and deaths of the Buddha and Jesus” (Bentley, “Old World Encounters”). The story of the birth of the Buddha was well known in the West, and possibly influenced the story of the birth of Jesus: Saint Jerome (4th century AD) mentions the birth of the Buddha, who he says “was born from the side of a virgin”. Also a fragment of Archelaos of Carrha (278 AD) mentions the Buddha’s virgin-birth.

The main Greek cities of the Middle-East happen to have played a key role in the development of Christianity, such as Antioch and especially Alexandria, and “it was later in this very place that some of the most active centers of Christianity were established” (Robert Linssen, “Zen living”).

FOR THE ORIGINAL TEXT AND REFERENCES SEE: MLAHANAS

Going Back to the Source

‘Greek Buddha’, by Christopher Beckwith

Abstract

Pyrrho of Elis accompanied Alexander the Great to Central Asia and India during the Graeco-Macedonian invasion and conquest of the Persian Empire in 334–324 BC, and while there met with teachers of Early Buddhism.

Greek Buddha shows how Buddhism shaped the philosophy of Pyrrho, the famous founder of Pyrrhonian scepticism in ancient Greece. Identifying Pyrrho’s basic teachings with those of Early Buddhism, Christopher I. Beckwith traces the origins of a major tradition in Greek philosophy to Gandhāra, a country in Central Asia and northwestern India.

Using a range of primary sources, he systematically looks at the teachings and practices of Pyrrho and of Early Buddhism, including those preserved in testimonies by and about Pyrrho, in the report on Indian philosophy two decades later by the Seleucid ambassador Megasthenes, in the first-person edicts by the Indian king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśi referring to a popular variety of the Dharma in the early third century BC, and in Taoist echoes of Gautama’s Dharma in Warring States China.

Beckwith demonstrates how the teachings of Pyrrho agree closely with those of the Buddha śākyamuni, “the Scythian Sage.” In the process, he identifies eight distinct attested philosophical schools in ancient northwestern India and Central Asia, including Early Zoroastrianism, Early Brahmanism, and several forms of Early Buddhism.

Beckwith then shows the influence that Pyrrho’s brand of scepticism had on the evolution of Western thought, first in Antiquity, and later, during the Enlightenment, on the great philosopher and self-proclaimed Pyrrhonian, David Hume.

Author

Christopher I. Beckwith is professor of Central Eurasian studies at Indiana University, Bloomington. His books include Warriors of the Cloisters, Empires of the Silk Road, and The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia (all Princeton). He is the recipient of a MacArthur Award.

Table of Contents:

Preface vii

Acknowledgements xv

On Transcription, Transliteration, and Texts xix

Abbreviations xxi

Prologue: Scythian Philosophy: Pyrrho, the Persian Empire, and India 1

Chapter 1 Pyrrho’s Thought: Beyond Humanity 22

Chapter 2 No Differentiations: The Earliest Attested Forms of Buddhism 61

Chapter 3 Jade Yoga and Heavenly Dharma: Buddhist Thought in Classical Age China and India 110

Chapter 4 Greek Enlightenment: What the Buddha, Pyrrho, and Hume Argue Against 138

Epilogue: Pyrrho’s Teacher: The Buddha and His Awakening 160

Appendix A The Classical Testimonies of Pyrrho’s Thought 180

Appendix B Are Pyrrhonism and Buddhism Both Greek in Origin? 218

Appendix C On the Early Indian Inscriptions 226

Endnotes 251

References 257

Index 269

Aidan Baker & Tim Hecker – Fantasma Parastasie

ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ ΤΗΣ ΙΝΔΙΚΗΣ ΛΟΓΟΤΕΧΝΙΑΣ

![108006346[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/1080063461.jpg)

Ο Κωνσταντίνος Θεοτόκης ασχολήθηκε με τη μελέτη της αρχαίας ινδικής γραμματολογίας από το 1896 ώς το 1910. Φιλοδόξησε να παρουσιάσει ολοκληρωμένο το έργο του κορυφαίου Ινδού δραματικού ποιητή Καλιδάσα, με εισαγωγή και σχόλια. Το βιβλίο Ιστορία της ινδικής λογοτεχνίας αποτελεί ακριβώς την εισαγωγή αυτή. Ο ίδιος στον πρόλογο του βιβλίου εξηγεί με τρόπο σαφή τους λόγους που τον ώθησαν στη συγγραφή: «Για να δυνηθεί κανείς να καταλάβει ως πρέπει οποιοδήποτε μεταφρασμένο σανσκριτικό κείμενο, είναι χρεία να κατέχει σε γενικές γραμμές τουλάχιστο την ιστορία της ινδικής φιλολογίας»· και «στοχάζομαι αναγκαίο, μπροστά στα μεταφράσματα που επιχειρώ σήμερα να δημοσιέψω, να βάλω μίαν εισαγωγή στα ινδικά πράματα που εμπορεί να χρησιμέψει σαν πρόδρομος κάθε μετάφρασης από το ινδικό· με χρονολογική σειρά θα πασκίσω να εξετάσω την φιλολογική παραγωγή της Ινδίας, και κάθε φορά που θα παρουσιάζεται η ευκαιρία θα εξηγάω τες θρησκευτικές, τες φιλοσοφικές, τες κοινωνικές ιδέες του λαού εκείνου».

Το βιβλίο αποτελείται από πρόλογο και εννέα κεφάλαια: οι Βαιδικοί Ύμνοι· τα βράχμανα, τα Αράνιακα και οι Ουπανισάδες· τα Βαιδάγκα και τα Σμάρτα σούτρα· οι νόμοι του Μανού ο Βούδδας· η φιλοσοφία· η επική ποίηση (με ανάλυση εκτενή του Μαχαβάρατα και του Ραμάιανα )· το δράμα (αρχές της δραματικής ποίησης, ελληνική επιρροή στο σανσκριτικό δράμα, ιστορία της δραματικής ποίησης με ανάλυση όλων των έργων των μεγάλων δραματικών ποιητών Καλιδάσα, Χάρσα, Σούδρακα και Bhavabhuti) η νεότερη επική ποίηση, η λυρική και τα επίλοιπα είδη της φιλολογίας.

![Konstantinos_Theotokis[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Konstantinos_Theotokis1-300x220.jpg)

Λογοτέχνης και διανοούμενος που δέσποσε στα ελληνικά γράμματά στις αρχές του 20ού αιώνα, ο Κωνσταντίνος Θεοτόκης γεννήθηκε στις 13 Μαρτίου του 1872 στην Κέρκυρα.

Σε ηλικία 17 ετών αναχώρησε για το Παρίσι κι εγγράφηκε στη Φυσικομαθηματική Σχολή του Πανεπιστημίου της Σορβόννης. Δύο χρόνια αργότερα, γνώρισε στη Βενετία τη βαρόνη Ερνεστίνα Φον Μάλοβιτς από τη Βοημία, με την οποία παντρεύτηκε. Το 1895 απέκτησε μαζί της μία κόρη, αφού ήδη είχε εγκαταλείψει τις σπουδές του και είχε εγκατασταθεί στους Καρουσάδες, όπου αφοσιώθηκε στη μελέτη.

Ο Κωνσταντίνος Θεοτόκης επηρεάστηκε αρχικά από τη γερμανική ιδεοκρατία και ιδιαίτερα από τον Νίτσε. Συντροφιά με τον φίλο του Λορέντζο Μαβίλη συμμετείχε σε εθνικούς αγώνες, όπως στην εξέγερση της Κρήτης το 1896, αλλά και σε τοπικές πρωτοβουλίες, π.χ. εναντίον της απόφασης του δήμου της Κέρκυρας για την εγκατάσταση ρουλέτας στο νησί. Καταφέρθηκε, επίσης, εναντίον της πολιτικής του συγγενούς του υπουργού και αργότερα πρωθυπουργού Γεώργιου Θεοτόκη.

Οι ευρύτατες γνώσεις του και η γνώση ξένων γλωσσών -ήταν κάτοχος πέντε ομιλουμένων γλωσσών (ιταλικής, γαλλικής, γερμανικής) και άλλων πέντε από τις νεκρές (αρχαία ελληνικά, λατινικά, εβραϊκά, αρχαία περσικά, σανσκριτικά)- του επέτρεψαν να ασχοληθεί με μεταφράσεις αρχαίων ελλήνων και ξένων κλασσικών, ενώ την ίδια περίοδο δημοσιεύτηκαν και τα πρώτα του πεζά στα περιοδικά της εποχής.

Στην Ευρώπη, που είχε ταξιδέψει δύο φορές για ελεύθερη επιμόρφωση στα Πανεπιστήμια του Γκρατς (1898) και του Μονάχου (1908-1909), απαρνήθηκε τον Νίτσε και ασπάστηκε τον Μαρξ. Με τη δεύτερη επίσκεψή του στην Ευρώπη ήρθε σε επαφή και με την κίνηση των σοσιαλιστών της εποχής. Αλληλογραφεί και συντονίζει τις απόψεις του με εκείνες του ομοϊδεάτη του Χατζόπουλου κι επιστρέφοντας πρωτοστατεί στην ίδρυση του «Σοσιαλιστικού Ομίλου» και του «Αλληλοβοηθητικού Συνδέσμου Εργατών της Κέρκυρας» (1910-1914).

Κατά τη διάρκεια του πολέμου, προσχωρεί στο Κόμμα των Φιλελευθέρων, διορίζεται αντιπρόσωπος του κόμματος στην Κέρκυρα και το 1918 μετακομίζει στην Αθήνα. Με το τέλος του πολέμου του προσφέρεται η θέση του διευθυντή λογοκρισίας, αλλά ύστερα από δύο ημέρες παραιτείται. Διορίζεται προσωρινά ως έκτακτος υπάλληλος στην «Υπηρεσία Ξένων και Εκθέσεων» και οριστικά στην Εθνική Βιβλιοθήκη, πρώτα ως γραμματέας και ύστερα προάγεται ως τμηματάρχης β’ τάξεως.

Για να αντιμετωπίσει τα έξοδά του, προπωλεί τα έργα του στους οίκους Βασιλείου και Ελευθερουδάκη. Έτσι, έρχονται στο φως τα δοκιμότερα πεζά του («Κατάδικος», «Η ζωή και ο θάνατος του Καραβέλα», «Οι σκλάβοι στα δεσμά τους») και οι μεταφράσεις του, π.χ. από τον Γκαίτε («Ερμάνος και Δωροθέα»), από τον Σαίξπηρ («Οθέλος», «Αμλέτος», «Βασιλιάς Ληρ»), από τον Φλομπέρ («Η Κυρία Μποβαρύ», Α’ τόμος) και από τον Ρόσελ («Τα προβλήματα της Φιλοσοφίας»).

Το 1922 διαγνώστηκε ότι πάσχει από καρκίνο του στομάχου. Χειρουργήθηκε και αποσύρθηκε στην Κέρκυρα, όπου άφησε την τελευταία του πνοή την 1η Ιουλίου 1923.

Ali Farka Touré – The River – Full Album

Pyrrhonism: How the Ancient Greeks Reinvented Buddhism (Studies in Comparative Philosophy and Religion)

Pyrrhonism is commonly confused with scepticism in Western philosophy. Unlike sceptics, who believe there are no true beliefs, Pyrrhonists suspend judgment about all beliefs, including the belief that there are no true beliefs. Pyrrhonism was developed by a line of ancient Greek philosophers, from its founder Pyrrho of Elis in the fourth century BCE through Sextus Empiricus in the second century CE. Pyrrhonists offer no view, theory, or knowledge about the world, but recommend instead a practice, a distinct way of life, designed to suspend beliefs and ease suffering.Adrian Kuzminski examines Pyrrhonism in terms of its striking similarity to some Eastern non-dogmatic soteriological traditions-particularly Madhyamaka Buddhism. He argues that its origin can plausibly be traced to the contacts between Pyrrho and the sages he encountered in India, where he traveled with Alexander the Great. Although Pyrrhonism has not been practiced in the West since ancient times, its insights have occasionally been independently recovered, most recently in the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Kuzminski shows that Pyrrhonism remains relevant perhaps more than ever as an antidote to today’s cultures of belief.

Adrian Kuzminski “Your Money or Your Life

Approaching Truth in Early Greek and Early Buddhist Thinking

VOLUME DIRECTOR

GEORGIOS HALKIAS, University of Hong Kong

AUTHOR

CHRISTINA PARTSALAKI, University of Hong Kong

Heraclitus and the Buddha – Approaching Truth in early Greek and early Buddhist Thinking

EDITORIAL

Georgios T. Halkias, Assistant Professor of Asian Studies, The University of Hong Kong, georgios.halkias@gmail.com

It is common knowledge that since ancient times there have been Asian elements and influence on Greek cosmology without any doubt as for the readiness and capacity of the Greeks to engage in philosophical dialogue with people from near and far away lands. As early as the sixth century BCE, cross-cultural exchanges between Greeks, Indians and Persians are documented in the Persian Empire that fostered the international movement of people and tangible and intangible goods from the eastern coast of the Aegean all the way to the Persian satrapy of Bactria in modern-day Afghanistan. The well-known voyage of Carian Scylax of Caryanda in 517 BCE, written in Greek in a book nearly lost to us, describes his passage from the Kabul River in Paskapyrus to the Indus River and through the Arabian Sea to Suez. In the 5th century BCE, Herodotos reports on a unique class of itinerant Indian ascetics who were vegetarian, refrained from killing, while there are several recounted cases of eminent Greek thinkers travelling abroad and coming in contact with other civilizations including Egyptians, Persians and Indians. At the same time there are several recounted cases of foreigners travelling to Greece. The most notable among these being Abaris (Άβαρις), a space-walker (αεροβάτης or αἰθροβάτης) and a shaman-priest of the solar-deity Apollo. The hyperborean Abaris travelled across Greece holding onto a magical arrow that closely resembled a phurba well-known in Central Asian shamanism. Some of the Greek sources inform us that his lineage was passed on to Pythagoras who received the arrow and the sacred knowledge that may have come from the depths of Inner Asia and fertilized Greek thought. Without going into further details that would remove us from the purpose of this editorial introduction, we should note that it is not surprising to discover age old rituals and cosmological theories that were shared between Eurasian people even if these cannot always be documented by extant written sources.

It would be historically necessary to recognize that there were many channels of communication and exchange between the ancient Greek world and the Eurasian continent while Asians resided in Greece at different times. In the following comparative study, Christina Partsalaki offers a thorough philological analysis between two philosophers who probably lived in the same milieu in Asia Minor and the Indian subcontinent respectively. Even though Heraklitos of Ephesus and Śākyamuni the Buddha, came from different cultural, linguistic and geographical backgrounds, these two well-renowned philosophers had a common quest to uncover a higher truth, while their teachings and methods of delivery reveal a unique attempt to go beyond our commonplace views and collective ideas about the nature of reality. We should note that Greek philosophers at this time attempted to discover and analyse for the most part the fundamental elements and structures of our cosmos. Their preoccupation with morality, especially in the case of Heraklitos, signifies a primary task to describe a universal truth reflected in the microcosm of societies and individuals.

It is obvious that Partsalaki is not interested to sketch a common historical origin or a specific starting point in the development of the minds of these two wise men. Rather she is interested to let the sources, written in Greek and Pāli language, to reveal on their own their common assumptions concerning the “impermanence of all things,” “knowledge versus wisdom,” and “awakening as opposed to ignorance.” It is her intention to bring to light the interconnected nature of ideas and read the contributions of the Greek philosopher through a Buddhist lens without resorting to false hierarchies. In her own words:

The emphasis is not placed on which of these two persons and philosophies came first, is original or better than the other. On the contrary, the aim of the present study is to examine shared philosophical methods and topics which relate to the investigation of truth in the aphorisms of Heraclitos and the teachings of the Buddha, two contemporaries who were concerned with an essential differentiation between our “view about reality” and the “real state of things.”

Without doubt, it is especially important to let the thinkers express themselves without an attempt to promote a preconceived position. Relating early Greek with early Buddhist philosophy the author resists an established view that limits the thought of Heraklitos to the understanding of his successors, mainly Plato and Aristotle, who interpreted his doctrines in ways that supported their own philosophical ideas. In this way, she succeeds to deliver much more than what she promises in the introduction to her work. Through this academic and well-researched study she initiates a novel hermeneutic quest guided by the dialectic relation between language and interpretation, where the “text and its interpreter” constitute, according to the German philosopher Gadamer, an ongoing “fusion of horizons.” In the comparative spirit of a transcendental contemplation that developed in the East and the West, we discern the roots of a universal spiritual heritage that survived in different mystery cult forms during continuing migrations of the people of Eurasia. We are also confronted with the greatness of human inspiration that gives expression to a coveted truth that promises to liberate us from the fetters, deception and suffering of a reality dependent on the senses and subject to phenomenal truth.

Tim Hecker & Daniel Lopatin – Instrumental Tourist

Lin Ma: “Heidegger on East-West Dialogue: Anticipating the Event”, Routledge, 2008, 268pp

Reviewed by Eric Sean Nelson, University of Massachusetts Lowell

Lin Ma’s Heidegger on East-West Dialogue is a rigorous, detailed, and attentive study of Martin Heidegger’s complex, ambiguous, and overly interpreted relations with Eastern thought. In this work, Ma meticulously interrogates Heidegger’s constructions of the “Asiatic” and the “Eastern,” his references to Asian words, texts, and traditions, and his interactions with individuals from China, Japan, and — to a lesser extent — South and Southeast Asia. In this carefully crafted inquiry, Ma examines the texts and contexts of Heidegger’s occasional references to Eastern thought and Asia. This includes remarks that have been discussed multiple times in previous literature without sufficient attention to their context and trajectory. She also considers a number of previously unexamined remarks from recently published works and collections of correspondence. This book is indispensable reading for anyone interested in the actuality and possibilities of Heidegger’s thinking with respect to Eastern and intercultural philosophy.

Ma offers a critical and balanced — and accordingly less speculative and optimistic — assessment of Heidegger’s interest in Eastern thought and his import for East-West and intercultural dialogue. Through a meticulous reading of the texts, she convincingly and forcefully — indeed, devastatingly for overly indulgent interpretations — reveals the stakes and limits of Heidegger’s actual interest in and import for Eastern thought. Heidegger never carefully distinguishes the various cultures nor the varieties of what he considers Eastern thought, which is neither philosophy (metaphysics) nor genuinely inceptive thinking insofar as these both concern Being. Likewise, Heidegger’s significance for intercultural thought has been uncritically appropriated and imaginatively exaggerated in East and West.

This book is not another creative yet ahistorical work in “comparative philosophy,” which is one of the dangers of cross-cultural philosophy. Ma traces how Heidegger influenced East Asian intellectuals and how they drew connections between Heidegger’s thinking and Eastern traditions that in turn shaped the context of the question of Heidegger and the East and the formation of “resonances” between them. It should be noted, however, that previous interpreters have been more aware of these difficulties than admitted in this work, which is precisely why they stressed and over-emphasized the few resonances, influences, and connections that they recognized.

Ma examines Heidegger’s writings with reserve and attention to their content and contexts, and also the large amount of secondary literature devoted to Heidegger and the East, beginning with Heidegger’s early reception in Japan in the 1920’s and 1930’s. She rightly dismantles and demystifies much of this literature. There is much less of Buddhism and Daoism in Heidegger than the secondary writings suggest, some of which infer a hidden Eastern thread running through Heidegger’s thinking. On careful reading, the few actual remarks and passages of Heidegger reflect his own philosophical and cultural preoccupations and little concern for Asian texts, contexts, or even for his Asian students and interlocutors. Although these individuals developed original works of their own, Heidegger does not take interest in this dimension of their thought or underestimates and misinterprets them. Despite occasional expressions of interest in Eastern languages and texts, Heidegger never engaged in a systematic and sustained inquiry into them. The one serious potential counterexample of his brief study and “co-translation” of the Daodejing confirms his lack of sustained effort. He broke it off, either — according to Heidegger himself on different occasions — because of difficulties with the translator Paul Shih-Yi Hsiao or due to the radical alienness of the Chinese language. This radical alienness is not merely an empirical issue of the difficulty of learning Eastern languages; it reflects an ontological incommensurability between East and West and for which neither is prepared.

The Daodejing is the only Eastern text mentioned and discussed multiple times in Heidegger’s published works. His uses of it reflect his own philosophical preoccupation with the question of Being, emptiness, and language, so that he freely adopts the translations according to his own linguistic priorities without considering its Daoist or Chinese contexts. This is undoubtedly true of his uses of the other principal text associated with early philosophical Daoism: the Zhuangzi. The biggest gap in Ma’s book is the somewhat surprising lack of detailed consideration of the Zhuangzi, especially given how exactingly the other connections and influences are examined, and its crucial role in Reinhard May’s argument for Heidegger’s indebtedness to Chinese and Japanese thought in Heidegger’s Hidden Sources.[1]

Heidegger and Heidegger scholars have linked Heidegger’s Weg (way) and Laozi’s dao (way). Although they are both literally translated as “way,” and Heidegger knew of and played with the significance of dao, it is unclear whether they mean the same thing or “resonate” in any lucid manner given their radically divergent contexts and uses. Heidegger himself is ambivalent about “dao.” Dao appears like logos, Sein (Being), and Ereignis (enownment or non-ontic event) to be a guiding word yet it cannot have the same meaning as Weg since dao is not a guiding word of philosophy or thinking. Likewise, Ma argues that there is no compelling identity to be articulated between the Chinese word translated as being (you) and Heidegger’s Being (Sein). Nor is there between Daoist emptiness (wu) and Buddhist emptiness (kong), much less Heidegger’s nothing (Nichts); although I would add that these can be used to illuminate each other in their differences without presupposing a direct connection or indirect resonance.

Ma stresses the concreteness and contextuality of Laozi’s emptiness, as a functional part of the working of things, in contrast with the abstractness of Heidegger’s nothing but then seemingly undermines this point by appealing to Pei Wei’s (CE 267-300) critique of the abstractness and mystification of emptiness in Daoism. It is unclear, but perhaps the author wants to distinguish the concreteness of emptiness in the Daodejing from its abstraction in the later third-century Daoist thinkers of the xuanxue (“dark learning”) and in Heidegger. Here she would be following Confucian critics such as Pei Wei, who wrote On the Exaltation of Being (Chong you lun) that decries the emphasis on nothingness. Ma shows how Heidegger takes liberties with German translations of the Daodejing, which are themselves problematic, and considers contemporary scholarship and recently discovered earlier versions of the Daodejing that make Heidegger’s interpretation even less plausible.

Heidegger’s remarks concerning the East occur in Greco-German and European contexts. Heidegger’s reading the question of Being or its absence, as well as his forced interpretations of Chinese and Japanese words, is construed as dialogue, and his seemingly positive remarks are overemphasized while the negative are ignored. In such portrayals, Heidegger is interpreted as a universalistic, egalitarian, or pluralistic thinker of common humanity, of perspectives from divergent yet somehow equal primordial sources, or of radical multiplicity. These overlook Heidegger’s crucial claim that there is only one event (Ereignis) and only one beginning, and it is Greek.

Heidegger’s language has been interpreted as implying an alterity or radical difference that potentially includes multiplicity (i.e., the non-Western), but the difference that matters for Heidegger is immanent or internal to the origin and cannot be located elsewhere. Whether it is philosophy and thinking, the first and other beginning, the overcoming of metaphysics and thoughtful remembrance, or technological and poetic dwelling, these do not concern or address non-Western sources insofar as they are first and foremost about Greek origins.

For Heidegger, Being is persistently a question of the German (in the 1930’s and early 1940’s) and later European and Western confrontation with the history of Being from its Greek origins to modern technology. In relation to this unique Western history of Being, and its needed transformation through confronting that history, the Eastern is constructed as an ahistorical realm. Eastern ways of thinking and living are secondary and derivative to a historical transformation that can only be a Western self-transformation. Even though East Asian words and persons are mentioned more frequently than the Judaic, Islamic, or African in Heidegger’s comments, the Eastern is separated and postponed to an indefinite future dialogue for which we are unprepared.

Heidegger is concerned with how Eastern traditions supposedly deemphasize the privilege of the human — as the guardian of the clearing and openness of Being — and links the East with the irrational, mystic, and nihilistic. The author raises but does not draw out the context and implications of a number of issues raised by Heidegger’s stressing the priority of humans as the guardians of the clearing in response to what he interprets as the equality of beings in Eastern traditions. Such a discussion could shed important light on the contested issue of humanism and anthropocentrism in his thought.

Whereas the West is world-historic, the East — despite its long practice of writing history and its significance in Confucian thought — is unlike the West in being fundamentally ahistorical. “Asia” and the “Asiatic” are identified with Soviet Russia in the 1930’s, and associated with impersonal and barbaric multitudes. The rhetoric of the “Asiatic” indicates a radical alienness, fatalism, and threat. Ancient Greece, Germany in the 1930’s, and the contemporary West must overcome the Asiatic by staying within themselves and returning to what is properly their own calling. Whereas Hegel argued that the Asiatic was sublimated into the Greek, Heidegger demands radical opposition and overcoming of its slavish fatalism and barbaric mythos.

Heidegger connects Asia with “dark fire” in 1962. Ma speculates that this might be the heavenly fire and might indicate that Heidegger assumes a less negative tone in the 1960’s. This claim is ambiguous given Heidegger’s previous connecting of the Asiatic with the darkness of the irrational, which might nevertheless be driven by its own flame, and his emphasis elsewhere on guarding the dark from false brightness and illumination. However, Heidegger notes that this is a fire to be reordered rather than guarded: “The Asiatic element once brought to Greece a dark fire, a flame that their [i.e., Greek] poetry and thought reordered with light and measure.”[2]

Heidegger’s lack of concern for genuine East-West dialogue, in the name of a depth of dialogue that can never be enacted in empirical or ontic communication, is demonstrated in the last two chapters through an extended analysis of “A Dialogue on Language: Between a Japanese and an Inquirer.” Heidegger’s fictionalized dialogue cannot be taken as a record of a conversation as it modifies factual details and the actual conversation with Tezuka Tomio — who indicated that this dialogue did not represent him and which he found one-sided and forced — on which it was purportedly based. This work is not a dialogue in which the Western thinker can learn from or change his mind because of anything said by the fictionalized Japanese interlocutor, who only begins to think when he speaks the language of Heidegger, and who provides (often misconstrued) Japanese examples to illustrate points in Heidegger’s thinking.

Heidegger contends that more dialogue under modern technological conditions perpetuates enframing (Ge-stell), according to which everything is a mobilized resource of standing-reserve (Bestand). Another more primordial way of saying (Sage) is needed. Heidegger’s model of dialogue is a monologue of Being’s own saying with itself, the appropriating or enowning event (Ereignis) to itself, or of the Greek origin with itself. This saying only occurs in Western languages and particularly in Greek and German. The linguistic ethnocentrism of the mid- and later Heidegger cannot be bracketed and his approach to Being and language retained. Its particular unique configuration is central to his argument given the formative world-disclosing essence of words. The uniqueness of Being and language in the West precludes drawing any general conclusions about a universalism or homeless cosmopolitanism that includes all human languages or relativism between an incommensurable multiplicity of languages.

“Homecoming” in Heidegger does not proceed through any foreign locale but through the “properly foreign” (i.e., Greece) rather than the alien Asiatic. The morning-land (Morgenland) that matters for the modern West or evening land (Abendland) is Greece and not a land in Asia. Heidegger’s onetime and atypical remark concerning “the few other great beginnings” occurs in the context of the fourfold (Ge-viert) of gods and mortals, heaven and earth, which Heidegger articulates exclusively in relation to Greece and Hölderlin. Other beginnings do not plausibly refer to non-Western sources. The Greek-European dialogue could be interpreted as a model for intercultural encounter and dialogue. But it is not and cannot be one given Heidegger’s stress on the uniqueness of the Western history of Being from metaphysics to modern technology, which is where the danger and the saving power within the danger both arise.

Heidegger’s Eurocentrism is not necessarily excusable by being anti-modern and suspicious of Westernization in the sense of intensifying technology, rationalization, and globalism. Heidegger mentions how this planetary civilization rooted in Western metaphysics has impacted the East and the world, and interpreters consequently sense that there is an anti-Eurocentric dimension to his thinking. This is correct to the extent that the West is identified with modernity and globalization; it is incorrect insofar as the West is still inherently beholden to its Greek beginnings. For the sake of both West and East, Europe must encounter again anew and renew its origins, which are Greek. While the West awaits the saving power, the world awaits the renewal of the West from out of itself and only then can a genuine encounter and dialogue take place. Whereas an earlier generation of Japanese philosophers interpreted Heidegger as a “necessary detour” for rethinking Zen Buddhism, Heidegger warns in the Spiegel interview of “any takeover (Übernahme) of Zen Buddhism or any other Eastern experiences of the world.” Even when East-West dialogue is introduced as a possibility, it is left undetermined for the future. Heidegger’s strategy of anticipating the event of such an encounter and dialogue, while concurrently deferring it into the distant future in the name of a preparation through exclusively Greek origins, precludes its enactment. It inhibits acknowledging and reflecting on the fact that such encounters and dialogues have been and are already underway from ancient Greece to modernity.

Tara Putra – In Dubland

![GBAMap[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/GBAMap1-177x300.jpg)

![Greek-Buddha-cover[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Greek-Buddha-cover1-197x300.gif)

![108006346[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/1080063461.jpg)

![Konstantinos_Theotokis[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Konstantinos_Theotokis1-300x220.jpg)

![51ZUHXj8QYL._SX329_BO1,204,203,200_[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/51ZUHXj8QYL._SX329_BO1204203200_1-198x300.jpg)

Recent Comments