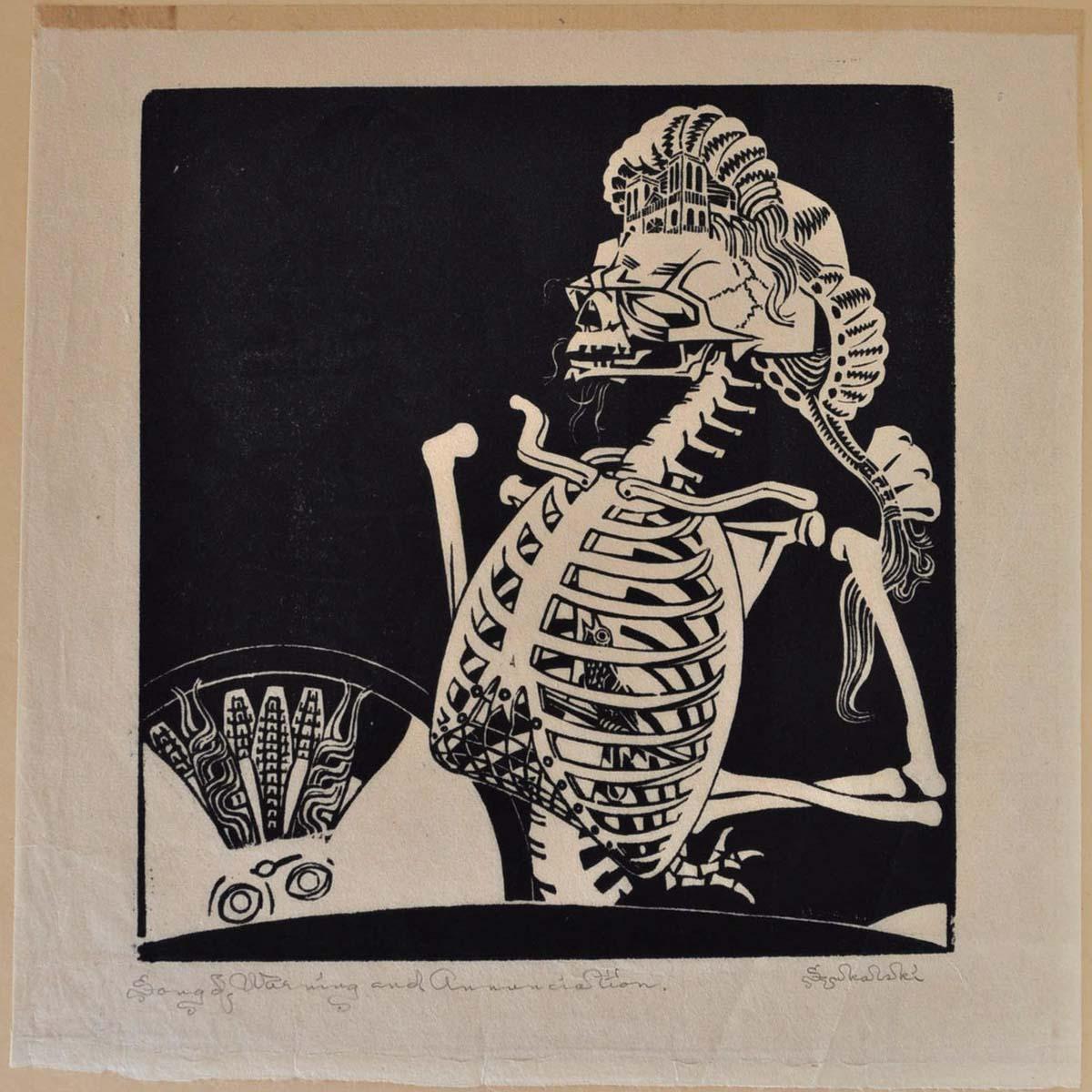

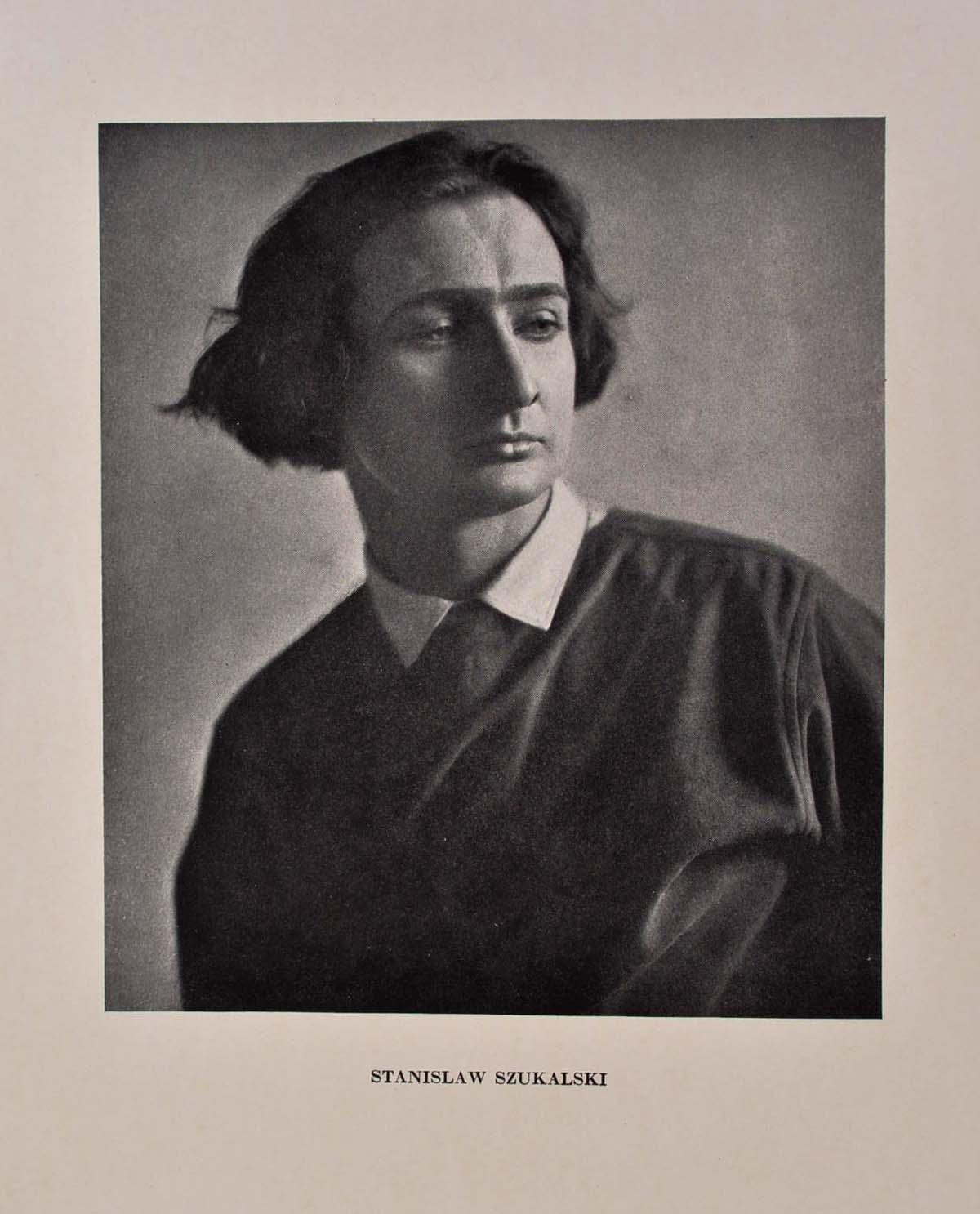

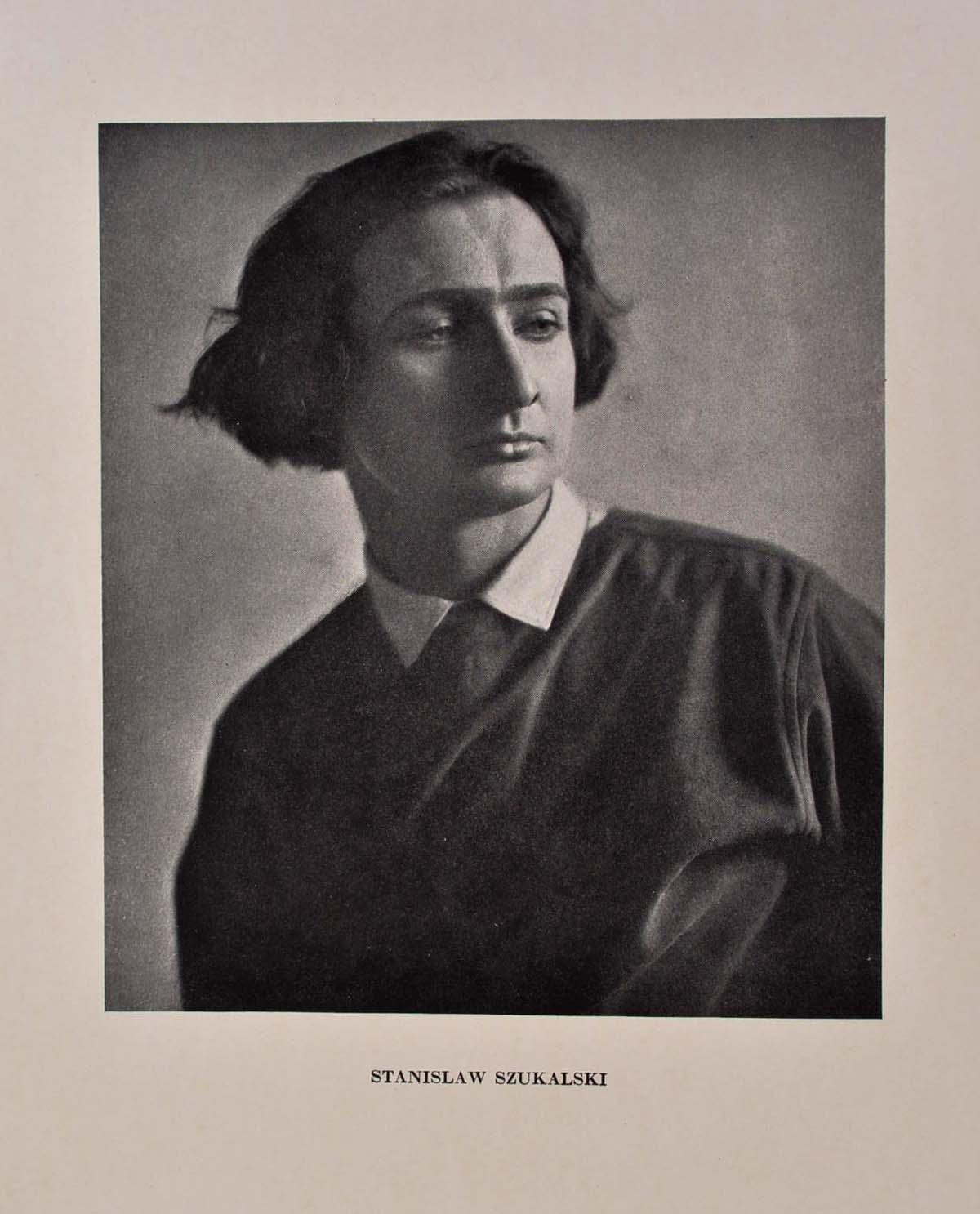

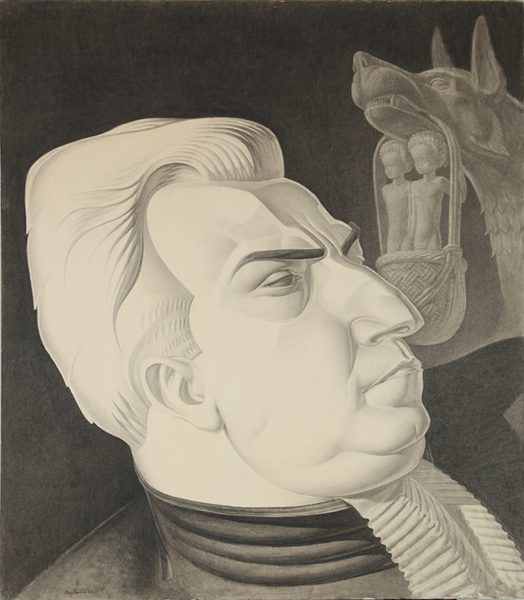

STANISLAV SZUKALSKI (1893-1987)-POLISH POETRY-KARAGIOZIS, IΙ

Posted on Jan 11, 2019 |

Σ΄αυτή την ιστοσελίδα της HELLENIC POETRY παρουσιάζουμε έργα του Πολωνού γλύπτη Stanislav Szukalski, και ποιήματα των Πολωνών ποιητών:

Bruno Jasienski

Tadeusz Rozewicz

Miron Bialoszewski

Τα ποιήματά τους στα Ελληνικά είναι από το βιβλίο του Σωτήρη Ε. Γυφτάκη, Πολωνοί Ποιητές, Εκδόσεις Λεξίτυπον.

Παρουσιάζουμε επίσης ποιήματα του Μενέλαου Καραγκιόζη εμπνευσμένα από το βιβλίο του Σ. Γυφτάκη.

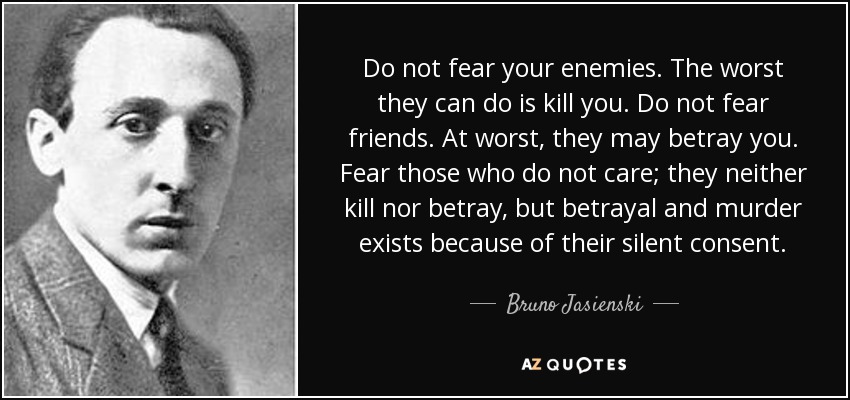

Bruno Jasienski (1901-1938)

Poet, prose writer, playwright. Born on the 17th of July 1901 in Klimontów near Sandomierz, died tragically, most probably executed on the 17th of September 1938 and buried in Butowo near Moscow.

Jasieński was born on 17 July 1901 in Klimontów near Sandomierz into a family of a provincial doctor. He attended a secondary school in Warsaw. After the outbreak of the World War I he continued his education in Moscow. While in Russia, he carefully observed the revolution of the literary avant-garde. Beginning with 1918 Jasieński stayed in Kraków where he studied the Polish Studies at the Jagiellonian University. There, he met the Futurists of the older generation: Tytus Czyżewski and Stanisław Młodożeniec. Together, they founded the futurist club “Katarynka”, which from 1920 on hosted poetry readings.

In the early 1920s Jasieński showed his talent as the author of manifestos (including Do narodu polskiego manifest w sprawie natychmiastowej futuryzacji życia / Manifesto to the Polish Nation For the Immediate Futurisation of Life; Manifest w sprawie poezji futurystycznej / Manifesto For the Futurist Poetry; as well as the co-author of the famous one-off issue Nuż w bżuhu / Nayf in the Abdomen). He also cooperated with avant-garde journals (“Zwrotnica” and “Almanach Nowej Sztuki”). After 1923 he joined the Communist left.

The beginnings of Jasieński’s career as a poet go back to the early 1920s. His texts published in the collection entitled But w butonierce / Shoe in a Buttonhole (1921) showed the poet’s fascination with the Russian Egofuturism, the sentimental and decadent movement and Anti-traditionalism. Later on (Pieśń o głodzie / Song of Hunger, 1923; Ziemia na lewo / Earth Leftwards, co-written with Anatol Stern, 1924) he reached for the poetry of Mayakovsky. Jasieński was a revolutionist and futurist both in content and language of his works. Eccentric metaphors and hyperboles were among the most often used rhetorical devices, also in prose writing (as in his micro-novel Nogi Izoldy Morgan / Legs of Izolda Morgan, 1923).

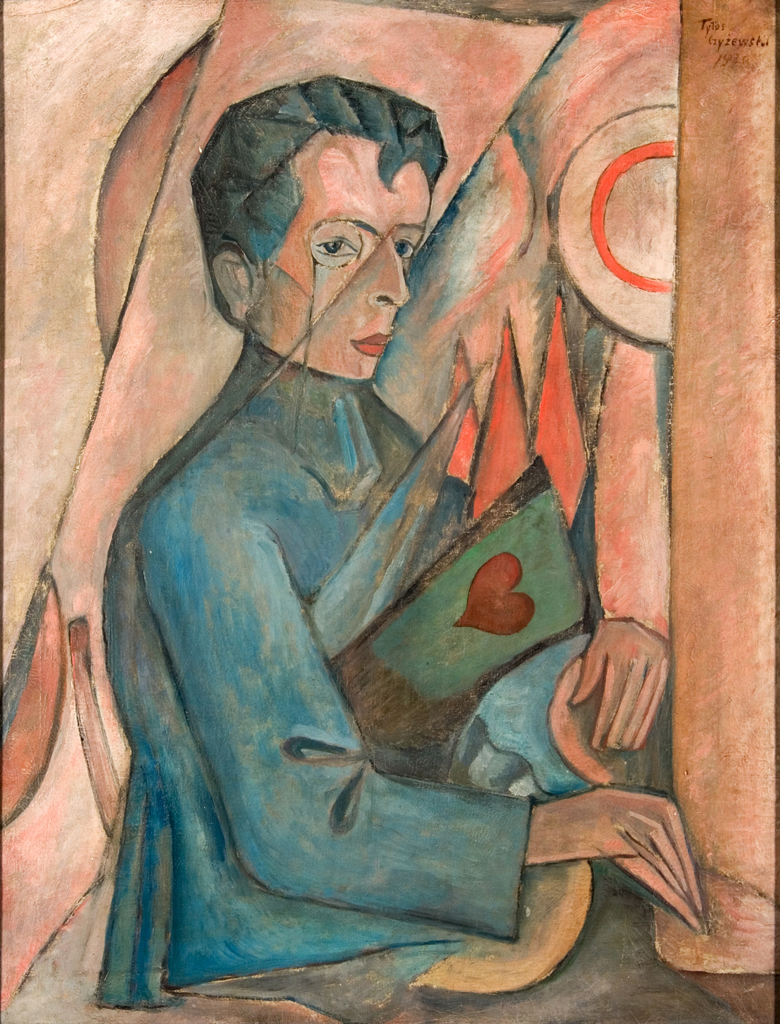

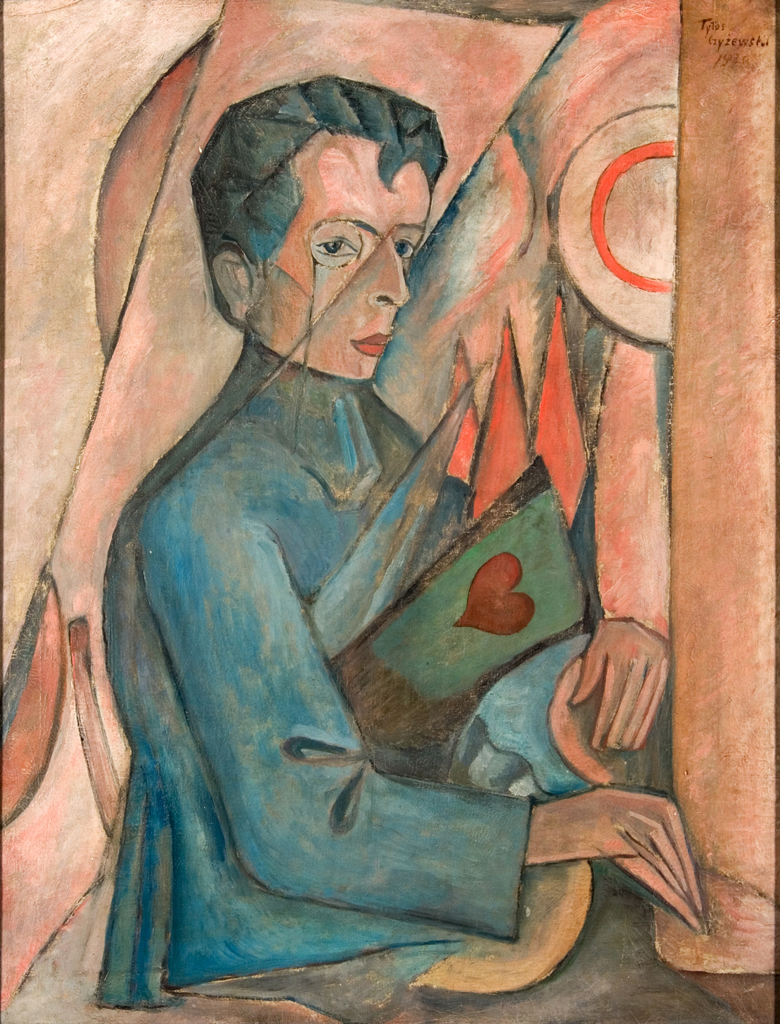

Tytus Czyżewski, “Portret Brunona Jasieńskiego” / “Portrait of Bruno Jasieński”,

1920, oil, canvas, photography: courtesy of the Museum of Art in Łódź

Κάθεται στο παγκάκι

Έχει βγαλμένα τα γυαλιά

Έχει κλείσει τα μάτια

Καθαρίζει τα γυαλιά

Ανοίγει την εφημερίδα,

Και περιεργάζεται τον κόσμο

Μαζεύει την εφημερίδα, σηκώνεται

Χάνει την ισορροπία, στηρίζεται στη μαγκούρα

Διαβάζει τα γράμματα πάνω στη ράχη του πάγκου

Περπατάει μιλώντας στον εαυτό του:

Ομιλείτε με τους πεθαμένους ποιητές…

Τον πλησιάζουν δυο γυναίκες

Ρωτάνε αν διαβάζει τη βίβλο,

Αν πιστεύει στη κόλαση

Τέλος του κόσμου, ο παράδεισος στη γη

Χαμογελάει κουνώντας το κεφάλι

Στα γεράματά του προτιμάει να μιλάει με τους ανθρώπους

Που σιωπούν.

Τότε περνάει μια γερακίνα

Περνάει με μαύρα φτερά

Στα χείλη τα κλείνει και φεύγει…

BRUNO JASIENSKI

ΧΑΝΕΤΑΙ Η ΙΣΟΡΡΟΠΙΑ

Διαβάζουν οι άνθρωποι εφημερίδες

γερακίνα τυφλή πετάει ως το τέλος του κόσμου

έχοντας κλεισμένα μάτια και χείλη που ανοίγουν διάπλατα

πλησιάζουν δυό γυναίκες με μαύρα φτερά

χάνεται η ισορροπία, φεύγει ο ουρανός απομακρύνεται

σηκώνονται ξάφνου λίγοι πεθαμένοι ποιητές

και με περιεργάζονται

περπατάει ο κόσμος μονάχος του

μιλώντας μονάχα στον εαυτό μου

«πιστεύεις» με ρωτάει «στη κόλαση;»

εγώ χαμογελώ

περπατάω με κεφάλι σκυφτό

κλαίγοντας

ανοίγουν τις πόρτες τα νεκροταφεία

μα σιωπούν οι τάφοι

μην ομιλείτε στους νεκρούς

γεράματα κι ο παράδεισος

ακόμη να φανεί στον ορίζοντα

© MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2019

As a result of censorship and police persecutions, in 1925 Jasieński left for France where he was active in the field of culture and theatre. At that time, he published the poem Słowo o Jakubie Szeli / Song on Jakub Szela (1926) which followed the poetics of a folk song. In Paris, Jasieński also wrote a catastrophic novel Palę Paryż / I Burn Paris (1928). When the translation of the work was published in “L’Humanité”, Jasieński was deported by the French authorities.

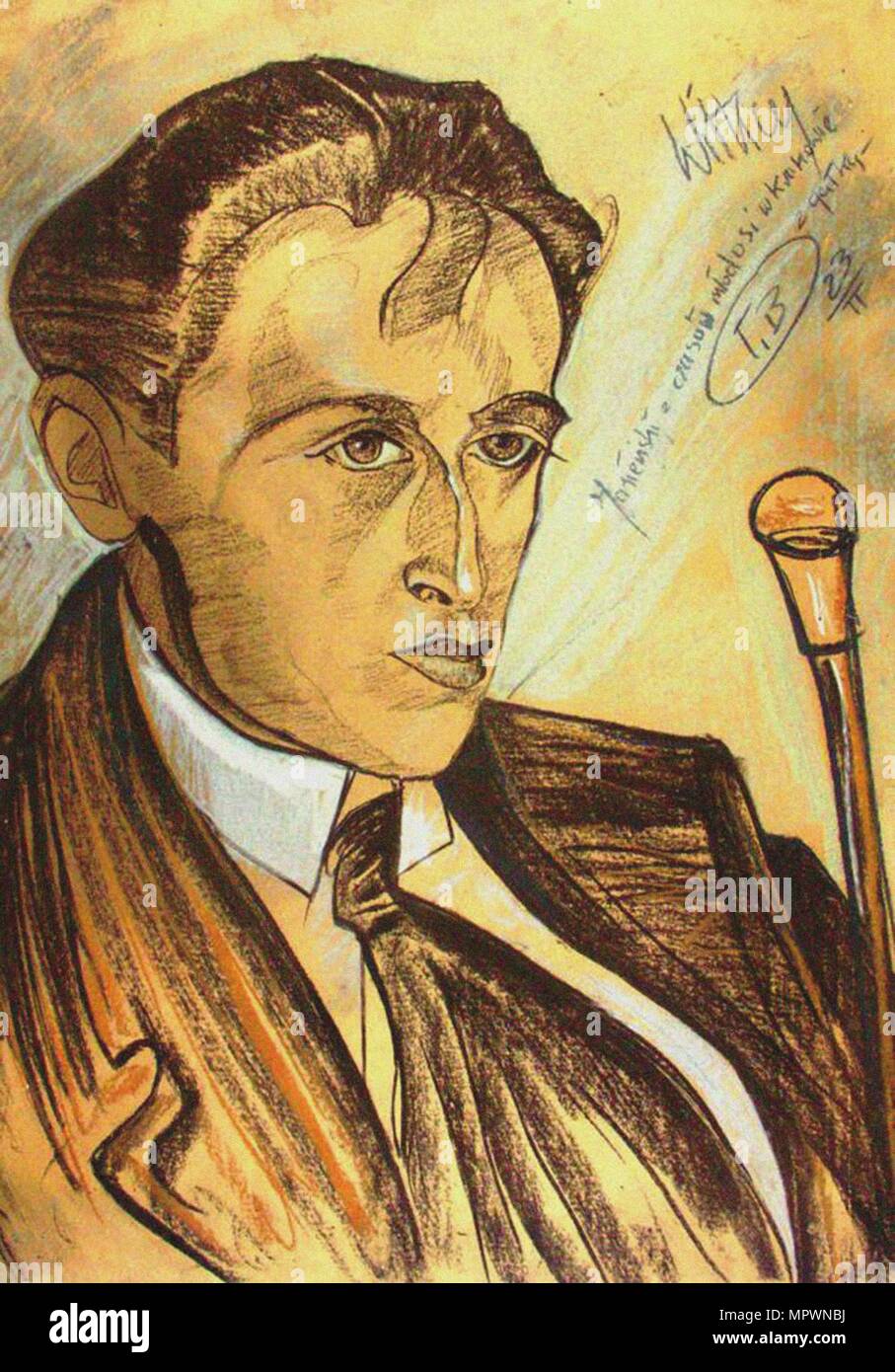

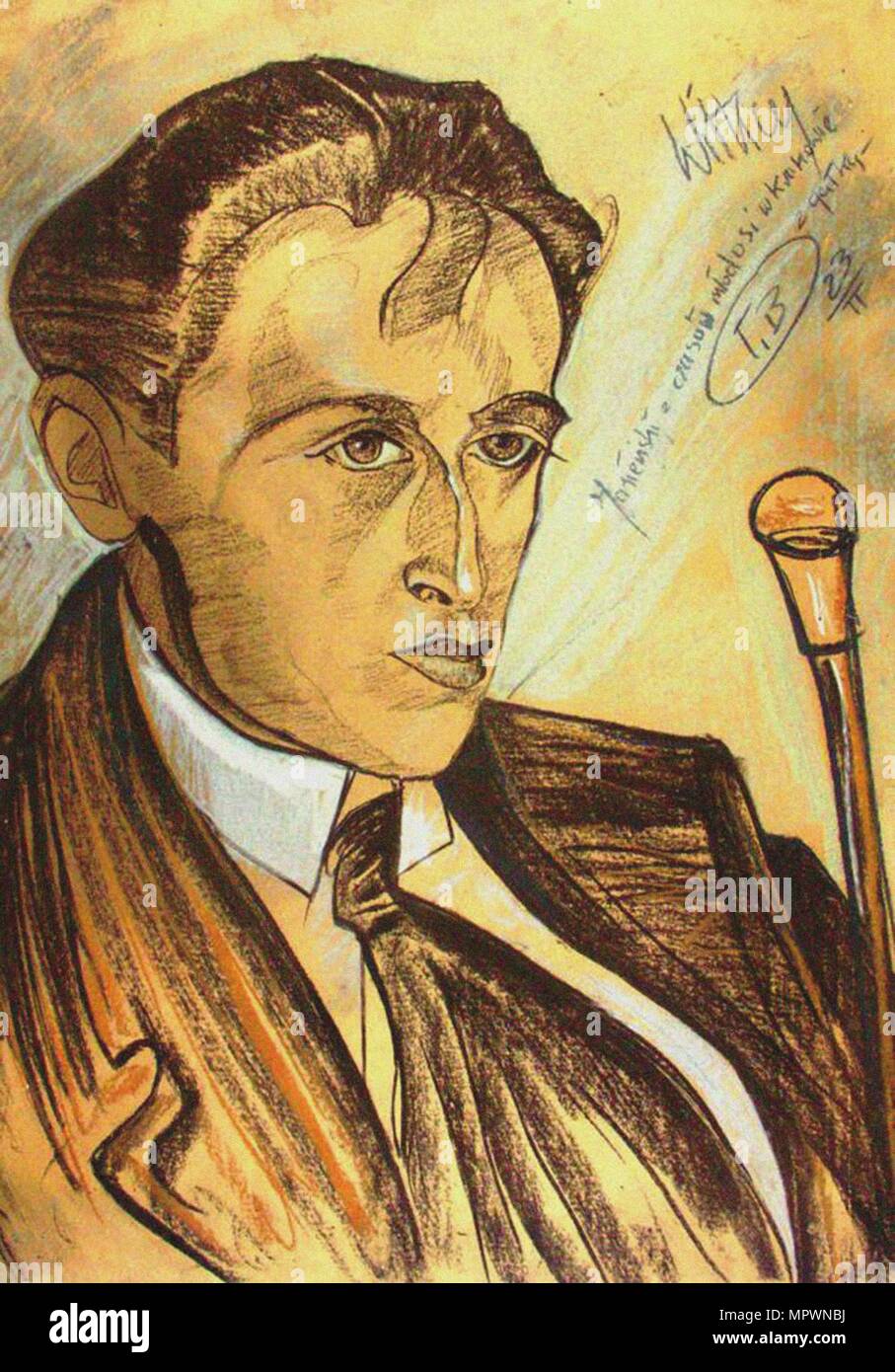

Portrait of the poet Bruno Jasienski (1901-1938), 1923

In 1929 Jasieński moved to the Soviet Union. During the 1930s he was active in the field of Russian culture and language. The poet received the Soviet citizenship, joined the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and became the member of the top management of the Association of Russian Writers. He also worked at the editorial boards of several journals (including “Kultura Mas” / “Culture of the Masses” and “Literatura Międzynarodowa” / “International Literature”). Jasieński was ceaselessly involved in the political and propaganda activities. His novellas, novels or documentary writing of that time are considered to be examples of Soviet literature.

At the end of the 1930s Jasieński was accused of “ideological alienation” and did not regain freedom until the end of his life. Sentenced to exile to Kolyma labour camp, he is said to die of typhoid. However, in various historical sources the death of the poet is shrouded in mystery.

Most probably, Bruno Jasieński was executed and buried in a mass grave in a collective cemetery in Butowo near Moscow. In his article, Piotr Mitzner writes that according the NKVD files Jasieński was executed on 17 September 1938.

THE WALK

The propeller’s hymn to Heredia’s words,

To words once lost in inky fog…

I played one of my comedies for her

Us two suspended in airy smog.

The sun pulsed through my head fervently.

The words flowed down into one refrain.

She watched me, expressionless; intently

Through the wild tango of her face-á-main.

I don’t know if she took what I said serious.

(In the corners of her lips two lines were wrote…)

Beneath us growled the rhythmic Bleriot

And the wind kissed her sky-blue throat.

BRUNO JASIENSKI

POEM HUNTER

Tadeusz Rozewicz (1921-2014)

Różewicz belongs to a brilliant generation of Polish poets—the half-generation after Czeslaw Milosz—initiated in the apocalyptic fires of history. He is a crucial part of the firmament—the “Generation of Columbuses”—that includes such other great modern poets as Zbigniew Herbert and Wislawa Szymborska. He grew up during one of the few periods of independence in Polish history, but came of age during the terrible years of World War II. Poland lost six million people during the war, nearly one-fifth of its population, and all young writers felt the crushing burden of speaking for those who did not survive the German occupation. “I’m twenty-four / Led to slaughter / I survived,” Różewicz wrote in “Survivor” (published in Anxiety in 1947). It was no boast. For him, poetry—or at least one kind of poetry—was murdered during the war. The Holocaust loomed over everything.

“A poet is one who believes / and one who cannot,” he declares.

The war was such a traumatic event that for a new generation of Polish poets it called all moral and aesthetic values into question. Those who survived could never believe in the future again. Nor could they revert to traditional forms of poetry.

He was among the first to catch the mood in a stripped-down poetry of drastic simplicity. Here is the beginning of “In the Middle of Life,” which reads like a new kind of primer:

After the end of the world

after my death

I found myself in the middle of life

creating myself

building a life

people animals landscapes

this is a table I kept saying

this is a table

on the table are bread knife

the knife is used for cutting bread

people feed on bread

man should be loved

I learned by night and day

what should one love

I answered man

Różewicz’s brutal simplicity enacts his suspicion of all general ideas and philosophies. He distrusts overarching concepts (“Concepts are only words”). He had a moment of embracing Communism, but soon gave it up, and over the years he has shown himself to be temperamentally allergic to political creeds or ideologies, public speech, sobbing superpowers from the East or West. He is alert to official lies and recognizes that evil comes “from a human being / always a human being / and only a human being.” His clear-eyed view of humanity is one of the constants of his work. “It would be best to go insane / you’re right Tadeusz,” he writes to his friend Tadeusz Konwicki, “but our generation never quite goes insane / to the very end/ it keeps its eyes open.”

[…]

For more than sixty years, Tadeusz Różewicz has remained utterly true to his values and commitments, to his dark view that “nothing begets nothing.” He is spare and uncompromising, a magician without robes. “My poetry,” he writes, “justifies nothing / explains nothing / renounces nothing / encompasses no whole / fulfills no whole.” And yet: “it obeys its own imperative / its own capabilities / and limitations / its loses against itself.”

As he writes in “so what it’s a dream”:

I write on water

from a few sentences

from a few verses

I build an ark

to save something

from the flood

which catches us by surprise

The Polish poet, playwright, screenwriter, novelist, satirist and translator of Hungarian poetry. One of the most versatile and creative continuators of the Polish and international avant – garde. Member of the Polish Writers’ Association. Often mentioned as a candidate for the Nobel Prize. Tadeusz Różewicz died on April 24, 2014.

The War, the forest and the pen

In 1939 Różewicz began working as an errand-boy, a warehouseman, and apprentice carpenter in the Bent-wood Furniture Factory – Thonet to help support his family. It was at this time that Janusz Różewicz, the first literary mentor to his brother, introduced him to the Polish literary underground. After a six-month training in an underground Officer Cadet School, Tadeusz was sworn into the Home Army (codename ‘Satyr’) to fight as part of the guerrilla troops from June 26, 1943 to November 3, 1944.

During this time he wrote poems and edited the newspaper Czyn Zbrojny (Armed Action). He published the tome Forest Echoes, which contained poems, epigrams, humoresques and patriotic, poetic prose together with Janusz in 1944. In these first pieces of Różewicz we can observe a passion for the works of Juliusza Słowacki and Stefan Żeromski, as well as a spiritual dilemma akin to his contemporaries such as Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński and Tadeusz Gajcy, particularly as they relate to the circumstances of war.

In 1943 Janusz Różewicz wrote to his brother, ‘You’ll write better than me, you’ll be a better poet…’ In July that year he was arrested by the Germans and was shot and executed on August 3, 1944.

A new shape of poetry

[…]

He became involved with the neoavangardist Grupa Krakowska, whose members include Tadeusz Kantor, Jerzy Nowosielski, Kazimierz Mikulski, Andrzej Wróblewski and Andrzej Wajda.

Różewicz gave a new shape to poetry by rebuilding a sense of meaning in life after the tragedy of Auschwitz […]

Różewicz fled to escape the communist regime 1950, the same year his friend Tadeusz Borowski went to Berlin. There he again became fascinated with the universality and the “greyness” of human existence in line with the philosophical ideology of Eyelash by Leopold Staff.

[…] After a year in Hungary, Różewicz came back to Poland and settled in Gliwice with his wife Wiesława. […] The couple lived in poverty away from the literary turmoil. In the book Czas, który idzie (Time to Come) he made ironic remarks about the superimposed order: ‘Communism will elevate people/ wash off the time of scorn,’ […]

The political thaw after the death of Stalin and the events of 1956 opened Poland to the West. Fascinated by the works of the Paris avant-garde, particularly Beckett and Ionesco, he wrote the drama Kartoteka (The Card Index), [..] and contribution to the theater of the absurd. More abstract, neobaroque and formist trials can be found in the poem Zielona róża (The Green Rose) and the tome Nic w płaszczu Prospera (Nothing Dressed in Prospero’s Cloak), parallel with Miłosz’s That.

In his contemporary poetry the author expresses the unrests and embitterments of a generation defined by wartime. In line with his experiences in the Home Army, Różewicz shows a world of relative values with man objectified and dominated by biology or technology. The I-speaker in his poems is a disintegrated personality, devoid of self and lost in a world of collapsing form.

[…]

The book of condolence for Tadeusz Rozewicz is displayed at Wroclaw’s City Hall, 2014.

Before Lachman’s cameras Różewicz stated his ‘Discourse about the Void’:

…The Void rages. Completeness doesn’t have to. The void has to make itself visible. The void in which biology struggles. The devil is also a void – its strength lies in the fact that you cannot grasp it, it doesn’t have a form. And this void is growing. And what happens in it: the most complicated weaponry as yet unseen by any man. Biologically (…) Syphilis or cancer do not threaten or scare us as much as AIDS. Committees gather to recommend the use of condoms, which in turn are forbidden by the Holy Congregation. All this beguiles our life.

[…]

Nevertheless, Różewicz demonstrated an excellent feel of the stage during a soiree in the National Theater in 1998:

…What is first? Writing? No. Reading is first. When you’re my age, you begin to feel that what you read is equally important to what you write. Sometimes more important, more interesting. Poetic soirees should change. Whenever I listen to my poems read by somebody else, I get the urge to correct them. Or to read somebody else’s. I recently came back to Demons by Dostoyevsky, maybe after forty years. There is a genial masterpiece of a description of a soiree. An old writer Karmazinov – whose character was inspired by Turgieniev – he cannot finish reading his “Merci, Merci” humoresque… He read, and read until the young people started teasing him. I was quite abashed by the whole description.

His bitter account with the contemporary past, as it tries in vain to find itself in the chaos of contemporary life, is illustrated in his dramas. His debut play is The Card Index (written in the years 1958-1959). […]

The Card Index consists of two images: the internal emptiness of the Character and a flood of phenomenae, people and objects that flows through his room.

[…]

It was a time of subversive topics such as the illegal trade of human organs, or the argument of the rabbis to give their seal of approval for kosher vodka produced in Polish distilleries. An entire poem is comprised of newspaper adverts. There’s another, especially ironic, poem composed of fragments of parliamentary debates. Różewicz, a chronic forerunner, proved that with the disappearance of censorship a new habit came about – uncontrolled garrulity and verbosity. He had found the danger and mocked it in a pastiche of parliamentary debates dominated by empty routine and formalities.

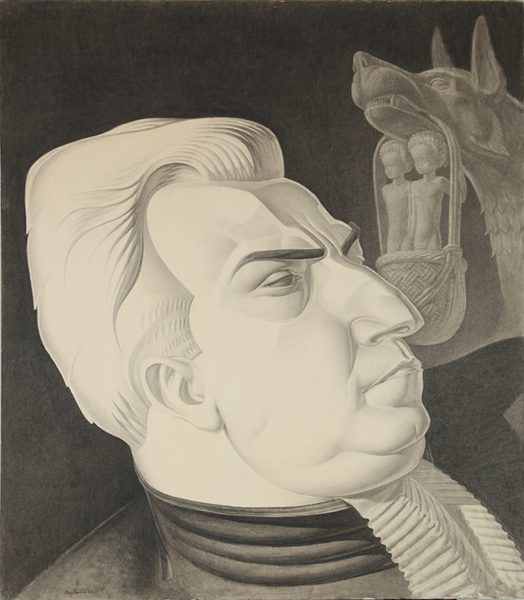

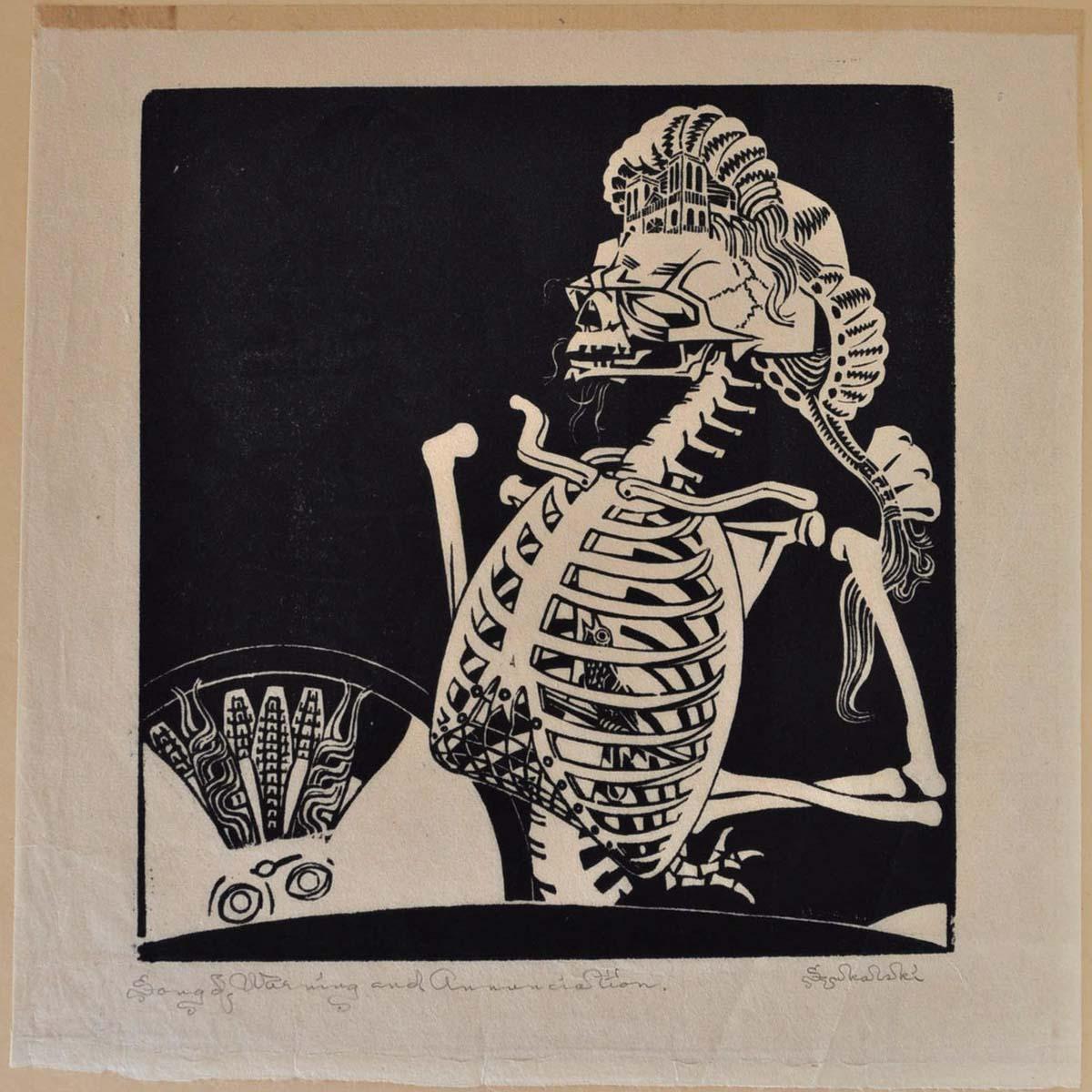

“Grave of the Unknown Soldier,” a 1971 Conté and ink on paper by Stanislav Szukalski

ΟΡΑΣΗ-ΕΝΟΡΑΣΗ

Είδα μες την αλήθεια

που ‘ταν μισή αγάπη ψεύτικη

και μίσος μισό μα τόσο κακό

τους κομματιασμένους ανθρώπους

εγώ ήμουν οδηγημένος

από μια όραση κοφτερού φωτός

σκέτο μαστίγιο

οι κρεατοφάγοι ίσως θεωρούν αρετή

τις σφαγές εκατομμύριων ζώων

ψάχνω τώρα κάποιο νόημα

να μου ξαναδώσει πίσω λίγη ζωή

θεωρούμε πλέον ως ο άστεγος δάσκαλος

όμως οι μαθητές του προκόψανε

γίναν νεκροθάφτες, οδοκαθαριστές

γενικώς επέλεξαν επαγγέλματα ειρηνικά

νοσοκόμες-μαθήτριες λοιπόν ελεήστε με

είμαι τώρα πενήντα τρία ετών

εικοσιτεσσάρων χρόνων καταραμένος

κι όλο ηλικιώνομαι

σώθηκα βλέπεται στα γερατειά

πιάστηκα σε πελώρια κύματα απάνω

κι έτσι δεν πνίγηκα

οπότε ποιό είναι το αληθινό μου όνομα;

ο σωσμένος τρελός, ζώο παρανοημένο

από έννοιες πολιτισμικές

πληθωρισμός σκέψης

είδα πράγματα τερατουργήματα

αφού είχε ο γλύπτης χέρι λεπρό

ψυχή μολυσμένη

καρδιά δήθεν βουτηγμένη σε κολυμπήθρες

αρετής και νοήματος φιλοσοφικού

ανθρώπινο πλάσμα ακατοίκητων σπλάχνων

με παρατσούκλι:

«ο δισεκατομμυριούχος ζητιάνος»

πιο φτωχικά πλούσιος δεν γινόταν

ζυγίζει προσεχτικά τους στίχους

πέστε το αν θέλετε ανδρεία ή δειλία

της ποίησης

είναι άδεια η ανυπαρξία φίλε ιεραπόστολε

γιομάτη κουφώματα και τρύπες

κακίας πίστης

η ομιλία τούτη δόθηκε προς τιμήν

ανθρώπων δίχως ακοή ή όρασης-ενόρασης

η μητέρα κάποιου βρέφους

καθώς σκοτώθηκε πάνω στη γέννα

είναι ίσως ο μονοσήμαντος δολοφόνος;

η μετωπική σύγκρουση;

αν θέλετε να μοιρολογήσετε

εγώ έχω ακόμη ένα κορμί

γιομάτο ανάσες και συναισθήματα

θα σας προσφέρω ίσως

μονάχα θλιμμένες λέξεις

εικοσιτεσσάρων χρόνων

κι ήδη μ’ άγγιξε η αιωνιότητα

ήταν άραγες χάδι εχθρικό;

φίλος φωσφορίζων στο σκοτάδι;

«Είδα» λέει ο θεός αίματος

ανθρώπινες ομορφιές τυφλωτικές

παπαδαριό κι άλλα τέτοια

κουραφέξαλα

θρησκευτικού ψεύδους

ας σου επιστρέψει ο θάνατος

εν αγνοία του

την χαμένη αγνότητα

© MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2019

Είμαι εικοσιτεσσάρων χρόνων

Σώθηκα

Οδηγημένος στη σφαγή

Είναι άδεια ονόματα και μονοσήμαντα

Άνθρωπος και ζώο

Αγάπη και μίσος

Εχθρός και φίλος

Σκοτάδι και φως…

Ωσάν το ζώο σκοτώνεται κι ο άνθρωπος

Είδα:

Άμαξες με κομματιασμένους ανθρώπους

Που ποτέ δεν θα σωθούν

Νοήματα παραμένουν και λέξεις

Η αρετή και η κακία

Η αλήθεια και το ψεύδος

Η ομορφιά και η ασχήμια

Η ανδρεία και η δειλία

Ίδια ζυγίζει η αρετή και η κακία

Είδα:

Άνθρωπο που ήταν ένα και το αυτό

Γεμάτος από αρετή και από κακία…

Ψάχνω το δάσκαλο και το μάγιστρο

Να μου επιστρέψει την όραση

Την ακοή

Και την ομιλία

Να δώσει ξανά νόημα κι όνομα

Στα πράγματα και στις έννοιες…

Είμαι είκοσι τεσσάρων χρόνων

Σώθηκα

Οδηγημένος στη σφαγή

TADEUSZ ROZEWICZ

ΙΣΟΤΗΤΑ

Kομπιούτερ, πόρνες τρισδιάστατες

διαδίκτυο, πληθώρα αεροπορικών ταξιδιών

όμως αχώριστη πνευματική λειτουργία ο στίχος

στοματικός παράδεισος τσιμπουκιών

καπότες ευρύχωρα φιλικές, εξωτικές διακοπές

νιώθω ευτυχισμένος μονάχα όταν είμαι καυλωμένος

μα υπάρχει καλύτερη διασκέδαση από τη ποίηση;

κακή συνήθεια βέβαια η ανάγνωση-απόγνωση

η συνείδησή μου

βρέχει μπρος στη λάμπα του νου

λίγο σκοτάδι

απρόσμενα δροσερό

ασχολήθηκα για χρόνια πολλά

με στίχους ποίησης

κι οπωροκηπευτικά

επαναστατημένος ως το κόκκαλο

γιομάτος απρόσμενα ραγίσματα

μπαίνει από εκεί μπόλικο φως

δυστυχισμένο

ασκάλιστη ψυχή

γλυπτό-σπλάχνο

της πραγματικότητας

ο Μουσολίνι, ο Στάλιν κι ο Χίτλερ

είχαν ζωώδη φύση, παρτουζιάρικη

για αυτό κι επικράτησαν

ο νόμος της ζούγκλας

ίσως είναι τελικά ο πιο δίκαιος

εξαίσια λοιπόν η ποιήτρια

ας ξεσπάσει, ας ξεσπάσει την

σεξουαλική της οργή

στο φαλλοκρατικό τούτο

ακροατήριο

άλλες καλλιτέχνιδες

κάπως πιο φεμινίστριες

μιλάνε για την ισότητα

των δύο φύλων

λες κι η αγάπη που κρύβει μέσα της

τόσο μίσος, ο βίαιος έρωτας

η σεξουαλική έλξη κορμιών

που απεχθάνονται τη σάρκα τους

είναι απλές μαθηματικές εξισώσεις

στεγνής λογικής

τεχνοκρατικοποιημένης

υποστηρίζω τον σοσιαλοκομμουνισμό

όμως μονάχα στο γαμήσι απάνω

ωμό κρέας νόστιμο πολύ

κι άσε τους χορτοφάγους

ν’ αυτοκτονήσουν

τρώγοντας τις σάρκες

κάποιας ύαινας

αποστειρωμένης ειρήνης

λιοντάρι απεξαρτοποιημένο

από κάθε επιθετικότητα

ισοδυναμεί με ύπαρξη

ευνουχισμένη

έχει ο παράδεισος υγρασία πολύ

διάλεξε έναν ευρύχωρο τάφο

και χώσου μέσα

τις μοναχικές τούτες νύχτες

όπου η συνείδηση παράλογη

χορεύει, ακούγοντας μια

σιωπηλή μουσική πονεμένης χαράς

εγώ βρήκα καταφύγιο στα νεκροταφεία

υπάρχω δίχως τίποτα να σκέφτομαι

χαίρομαι λυπημένος

εκεί έκανα φίλους πολλούς

φίλους καλούς κι έμπιστους

που κράτησαν μια ζωή ολάκερη

κι αντέξαν

τι κι αν ήταν πεθαμένοι

δεν πειράζει

είναι ίσως ο θάνατος αρχή

ήμουν γεννημένος

στο τίποτα απολύτως

© MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2019

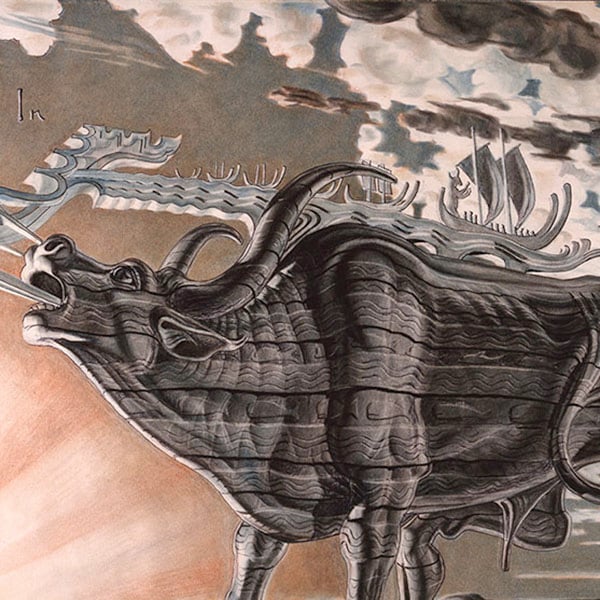

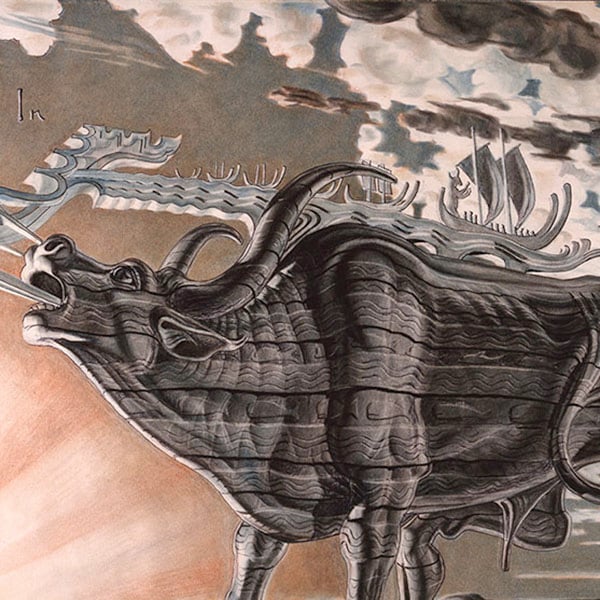

The Lowing Ox

ΧΑΡΟΥΜΕΝΗ ΑΥΤΟΠΡΟΣΩΠΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ

Δε σκέφτομαι πως είμαι δυστυχής

Χαίρομαι που σκέφτομαι

Σκέφτομαι πως χαίρομαι

Συνείδηση είναι ο χορός χαράς

Η συνείδηση μου χορεύει

Μπροστά στη λάμπα της βροχής

Στο κέλυφος του τοίχου, στο παντοπωλείο

Με τα επαναστατημένα οπωροκηπευτικά

Στα στόματα των φίλων που μιλάνε

Στο δικό μας χέρι απρόσμενα

Στο ασκάλιστο γλυπτό της πραγματικότητας

Στην πληθώρα της καλύτερης διασκέδασης

Η πιο εξέχουσα λειτουργία, αχώριστα που η συνείδηση χορεύει

Κι όταν ξεσπάσει ο χορός με τη συνήθεια κάθε κουβαριού

Θα πάω στον παράδεισο, όπου δεν αισθάνομαστε τίποτα

Όπου απ’ την αρχή ήμουν πριν να υπάρχω

Όπου πια μέχρι τέλος θα είμαι όταν δεν θα υπάρχω

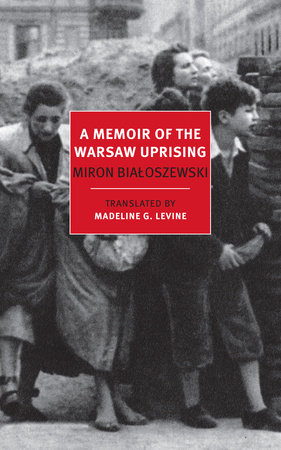

MIRON BIALOSZEWSKI

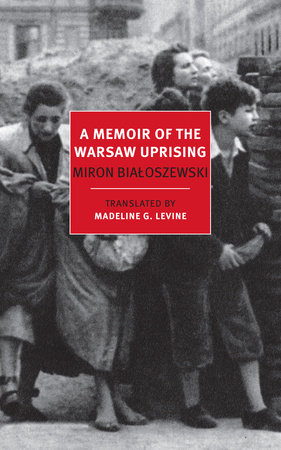

Miron Bialoszewski (1922-1983)

A Poet of Linguistics

Despite critics’ efforts to assign a category to the poetry of Miron Białoszewski, he remained ‘a distinct poet’ throughout his life. His poetry defies any classification and while he was associated with the generation of the war poets (Baczyński, Gajcy, Różewicz, Szymborska, Herbert), his poetics differed from theirs. The poet was an outsider by choice: he was not engaged in political life and avoided being associated with any organisations or poetry circles.

Aside from the references to 20th century avant-garde art, Białoszewski’s poetry distinguishes itself by a creative exploration of language. He is often referred to as ‘a poet of linguistics.’ In his poems, Białoszewski transgressed the borders of the established literary language and broke its conventions. The poet’s interests laid in such phenomena as: irregular, disturbed or awkward speech; mumbling, slips of the tongue and linguistic coincidence, inertia and automatism. Białoszewski often drew inspiration from the spoken, common and even the language of children. He was constantly testing the borders of the linguistic scheme. He did not create these linguistic puns for their own sake but in order to search for an fitting description of reality.

World War II and Poems

As one of the survivors of the Warsaw Uprising, Białoszewski pursued his education in spite of the German occupation, attending clandestine classes. He managed to pass his secondary school examinations and then took up Polish Studies at the underground University of Warsaw. Shortly after the end of the war he returned to the capital city where he worked first at the Main Post Office , and then from 1946 to 1951 as a journalist for newspapers: Kurier Codzienny [Daily Courier] and Wieczór [Evening]. Between 1951 and 1955 Białoszewski made a living writing poems and songs for children and teenagers in popular youth magazines together with Wanda Chotomska.

[…]

In 1955 Białoszewski published his poetry (with a foreword by Artur Sandauer in Życie Literackie (Literary Life) in a series devoted to five young poets just starting out, also featuring none other than Zbigniew Herbert, Jerzy Harasymowicz, Stanisław Czycz and Bohdan Drozdowski.

[…]

Theatre Arts

Even before publishing his debut collection, Białoszewski got involved in theatre arts. In 1955 jointly with Lech Emfazy Stefański and Bogusław Choiński he established a private experimental theatre (Teatr na Tarczyńskiej) where he staged various cabaret performances and dramas. Following its dissolution, Białoszewski established Teatr Osobny jointly with painter Ludwik Hering and actress and painter Ludmiła Murawska. It was located in his own apartment at the Dąbrowski Square. Białoszewski wrote plays for his own theatre – Osmędeusze and Działalność (Activity). The influences of a theatrical thinking are apparent in Białoszewski’s poetry.

[…]

Like no other artist of his generation, Miron Białoszewski embraced new technologies to scrutinise himself and his work. His experiments are immortalised in the tape recorded audio materials and were released in 2014 by Bołt Records.

CULTURE PL

Gate of Down

“A ballad of going down to the store”

First I went down to the store

by the stairs,

ah, imagine only,

by the stairs.

Then people known to people unknown

passed me by and I passed them by.

Regret

That you did not see

how people walk,

regret !

I entered a complete store:

lamps of glass were burning.

I saw somebody–he sat down–

and what I heard ? what I heard ?

rustling of bags and human talk.

And indeed,

indeed

I returned.

“Autoportrait as felt”

They look at me

so probably I have a face.

Of all the faces known

I remember least my own.

Often my hands

live in absolute separation.

Should I then count them as mine

Where are my limits ?

I am overgrown by

movement or half-life.

Yet always is crawling in me

full or not full

exist ence

I bear by myself

a place of my own.

When I lose it

it will mean I am not.

I am not,

so I do not doubt.

“My Jacobean fatigues”

My Jacobs of tiredness

Higher

Hclarion-colls of form

habitations of touch,

all serenities of senses.

Lowest of all, I.

From my breast they grow

stairs of reality.

And I feel nothing.

Nothing of juiciness.

Nothing of colour.

Not only I am not

one of the Testament heroes

but worse than a flounder

glued to the bottom to die

with balloons of breath

fleeing up,

worse than a potato mother

who put forth

enormous antlers of tubes

and herself is shrinking

up to disappearance.

Strike me

construction of my world!

WORLD LITERATURE FORUM

Recent Comments