STANISLAV SZUKALSKI (1893-1987)-POLISH POETRY-KARAGIOZIS, I

Posted on Jan 9, 2019 |

Σ΄αυτή την ιστοσελίδα της HELLENIC POETRY παρουσιάζουμε έργα του Πολωνού γλύπτη Stanislav Szukalski, και ποιήματα των Πολωνών ποιητών:

Konstanty Ildefons Galczynski

Karol Jozef Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II)

Jerzy Liebert

Jozef Czechowicz

Mieczyslaw Jastrun

Τα ποιήματά τους στα Ελληνικά είναι από το βιβλίο του Σωτήρη Ε. Γυφτάκη, Πολωνοί Ποιητές, Εκδόσεις Λεξίτυπον.

Παρουσιάζουμε επίσης ποιήματα του Μενέλαου Καραγκιόζη εμπνευσμένα από το βιβλίο του Σ. Γυφτάκη.

Konstanty Ildefons Galczynski (1905-1953)

Gałczyński was one of the most singular figures of Polish literature. His work is difficult to ascribe to any particular movement popular at his times (futurism, cubism, surrealism, experimental poetry, and neoclassicism), yet it moves swiftly between each of them. Throughout his life, he was associated with literary magazines from both ends of the politcal spectrum. In the interwar period, he collaborated with the extreme right wing Prosto z mostu, antisemitic and fascist. After the war, among his other artistic activities, he would create some of his works following the rules of socialist realism, the aesthetic doctrine of the times of the communist regime in Poland.

[…]

He was familiar with Latin, German, French, and English poetry and could easily read in all of these languages. In the interwar period, Gałczyński was studying classics and English at University of Warsaw. He did not graduate from neither of the courses. It was already then that he assumed a position he seemed to be particularly fond of – the prankster. He decided to give an oral presentation (although some sources claim it was an essay, or even an MA thesis;this is dubious as no written record survived) about a 15th century Scottish poet, Morris Gordon Cheats. Gałczyński presented a detailed analysis of his works, including numerous quotations he beautifully recited. The only issue was that Morris Gordon Cheats never existed.

[…]

In the beginning of World War II, Gałczyński had to join the army. He took part in the Polish September Campaign of 1939. He was very soon taken captive by the Russians, and later – Germans. Subsequently, he was a prisoner at a German prisoner-of-war camp. After the war, having visited Brussels and Paris in the meantime, Gałczyński came back to Poland. At that time, he started to co-operate with Przekrój magazine.

His work was incredibly versatile and saturated with imagery drawn from different sources (including poetry and art of the past – Gałczyński was generally well-read and educated), often put together in a surprising or even seemingly senseless manner – hence some literary scholars describe Gałczyński’s work as being on the intersection of the avant-garde and neoclacissim.

Nowadays, the poet is best remember for his absurd cycle Green Goose Theater (Teatrzyk Zielona Gęś), printed in Przekrój between 1946 and 1950. This series of very short dramatical forms is notable for grotesque and absurd humour. Already at his time, Gałczyński was considered to be the master of the ‘cabaret’ form in poetry, meaning creating works that would switch their mood and imagery often and vividly. Curiously enough, he is the author of the Polish translation of Ode to Joy, which became the Polish version of the European Union’s anthem many decades later.

Gombrowicz, another Polish writer notable for his use of grotesque and mockery, valued Gałczyński’s work very much and wrote

Gałczyński’s pieces are more edible to me than the work of others, because they contain a solid portion of prose, anecdote, psychology, politics even – so strongly merged into an organic whole with poetry that can only be treated as proof of the author’s absolute skill.

Unfortunately, Gałczyński’s work remains largely untranslated into English.

The grave of Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński and his wife Natalia on the Military Graveyard on Powązki in Warsaw.

He died on 6 December 1953, aged 48, following a third heart attack.

ΠΑΡΑΚΛΗΣΗ ΓΙΑ ΕΥΤΥΧΙΣΜΕΝΑ ΝΗΣΙΑ

Πάρε με στα νησιά της ευτυχίας και μ’ απαλόν αέρα

σα λούλουδα ανακάτεψε τα μαλλιά και λούσε με στα φιλιά

και λίκνισέ με, νανούρισέ με και κάλυψέ με με ύπνο μουσικό

Πάρε με στα νησιά της ευτυχίας να με γαληνέψεις

Δείξε μου τα βαθιά νερά, τα γαλήνια βαθιά νερά

Όταν τα αστέρια θα χορεύουν στα κλαδιά

Κι άφησέ με να ακούω τις πεταλούδες καθώς την καρδιά μου

Προσπερνούν

Κι αγκάλιασέ με έτσι με σκέψεις γαληνές σκύβεις πάνω στα νερά

GALCZYNSKI

ΑΚΡΟΓΙΑΛΙΑ ΕΥΤΥΧΙΑΣ

Ω νησί μου μουσικό

είχες βαθιά νερά ερωτικά

κι αστερόκλαδες γυναίκες

νανούρισε τες στα φιλιά

πως με γαληνεύεις τώρα

σε ακρογιάλια ευτυχίας

λούσε τις λικνισμένες σου πεταλούδες

σε σκέψεις κι αγέρηδες

ο ύπνος ο απροσπέλαστος

σκύβει απάνω μας

αγκαλιάζει μια καρδιά

ανακατεύοντάς τη μαλλιά λουλουδιασμένα

© M. KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2019

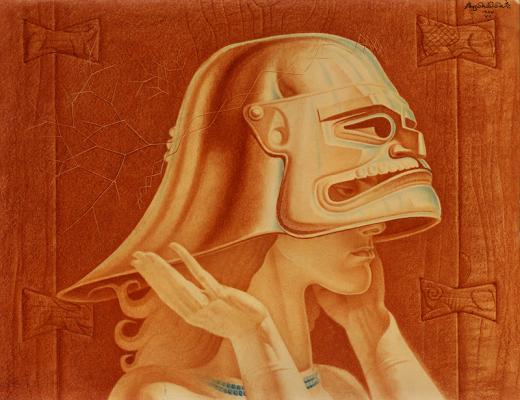

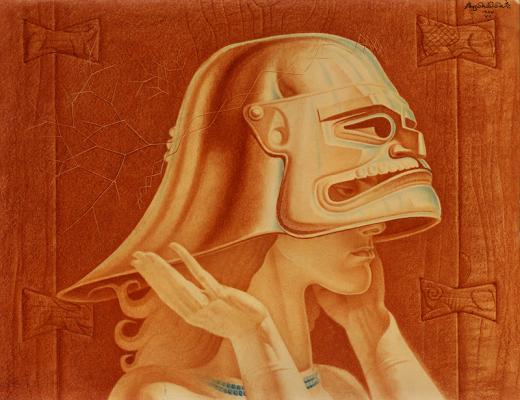

Ancestral Helmet

Karol Jozef Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II) (1920-1985)

Karol Jozef Wojtyla was an unknown Polish poet long before he became known to the world as Pope John Paul II. Some of the poems below were written when he was in his twenties. Others were written while he was a parish priest and auxiliary bishop of Kraków, during which time his work appeared in Polish journals under the pseudonym Andrzej Jawien. His poetry was later collected and published in The Place Within — The Poetry of Pope John Paul II, with translations and notes by Jerzy Peterkiewicz.

“From dust you came, and to dust you shall return”;

What had shape is now shapeless.

What was alive is now dead.

What was beautiful is now the ugliness of decay. And yet I do not altogether die,

what is indestructible in me remains!…

What is imperishable in me

now stands face to face before Him Who Is!

—From “Meditations on the Book of Genesis: At the Threshold of the Sistine Chapel”

Wojtyla was born in Wadowice, in an apartment that looked out on the Church of Our Lady where he would later serve as an altar boy. His birthday was May 18, 1920, an auspicious day for modern Poles, now known as “the Polish Miracle.” On that day, Marshal Jozef Pilsudski won a major battle and seized Kiev from the Soviet Union. It was Poland’s first major military victory in over two centuries. Wojtyla’s middle name was chosen by his father in honor of Jozef Pilsudski.

[…]

Known to family and friends as Lolek (a nickname that translates as “Chuck”), the future John Paul II learned about suffering at an early age when his mother died of heart and kidney problems in 1929, shortly before his ninth birthday.

[…]

When he was twelve, Wojtyla’s brother Edmund, a 26-year-old physician in the town of Bielsko, died of scarlet fever. Wojtyla himself had two brushes with death as a youth. He was hit once by a streetcar and again by a truck. “The pope’s youth wasn’t happy,” Father Joseph Vandrisse, a former French missionary and now a journalist, told TIME Magazine. “He has meditated a lot on the meaning of suffering…”

As a young scholar, Karol Wojtyla “drank in the suffering Poland” through literature and history. He loved the 19th century poets Slowacki and Mickiewicz, “in whom the beauty and pain of Poland was so alive.” He memorized Slowacki’s “The Slavic Pope,” a prophetic poem (which proved to be truly prophetic!) about a pope from the East who “will not flee the sword … Like God, he will bravely face the sword.

[…]

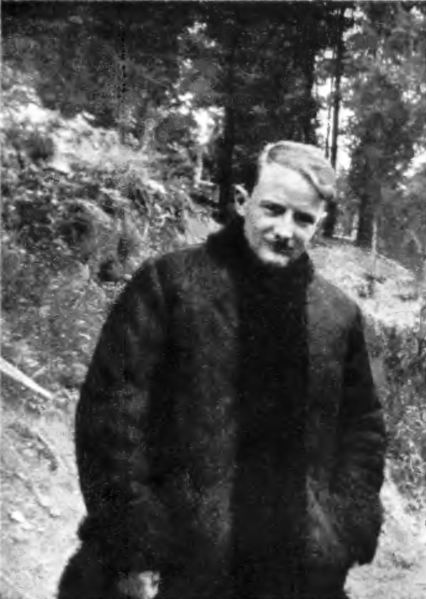

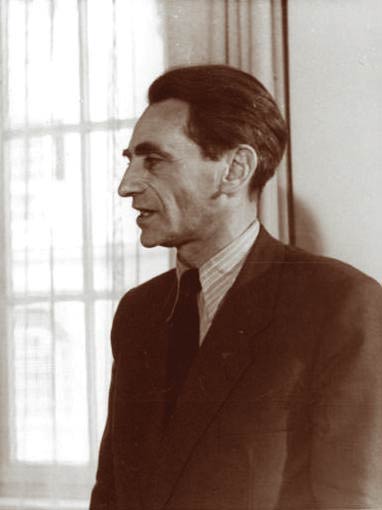

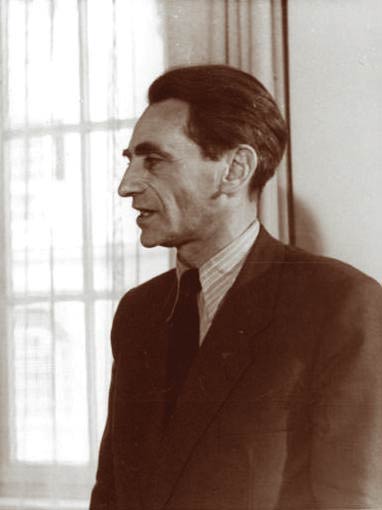

Like Ronald Reagan, Wojtyla was an actor. And a dark-haired, ruggedly handsome actor at that, as his picture to the left attests. In the early 1930’s, he met Mieczyslaw Kotlarczyk, who would teach him (and isn’t it an interesting “method” for a future Pope!) “the Living Word,” a style of performance rooted in Polish songs and Polish poetry as sung and recited after dinner in country manor houses. In Pope John Paul II: The Life of Karol Wojtyla, Fr. Mieczyslaw Malinski recounts that it was during this time that Wojtyla first came to the attention of the Archbishop of Kraków, Adamo Stefano Sapieha. Sapieha was visiting his school and young Wojtyla gave the welcoming speech. Impressed, Sapieha asked whether Karol intended to become a priest. A priest replied that his interests seemed to lie with the theater, “an answer which disappointed the archbishop!” To make matters perhaps worse, Wojtyla later joined an experimental theater group known as “Studio 38.” His love of the theater persisted, because later as a cardinal, he celebrated holidays with Krakow actors.

Like Ronald Reagan, Wojtyla was an actor. And a dark-haired, ruggedly handsome actor at that, as his picture to the left attests. In the early 1930’s, he met Mieczyslaw Kotlarczyk, who would teach him (and isn’t it an interesting “method” for a future Pope!) “the Living Word,” a style of performance rooted in Polish songs and Polish poetry as sung and recited after dinner in country manor houses. In Pope John Paul II: The Life of Karol Wojtyla, Fr. Mieczyslaw Malinski recounts that it was during this time that Wojtyla first came to the attention of the Archbishop of Kraków, Adamo Stefano Sapieha. Sapieha was visiting his school and young Wojtyla gave the welcoming speech. Impressed, Sapieha asked whether Karol intended to become a priest. A priest replied that his interests seemed to lie with the theater, “an answer which disappointed the archbishop!” To make matters perhaps worse, Wojtyla later joined an experimental theater group known as “Studio 38.” His love of the theater persisted, because later as a cardinal, he celebrated holidays with Krakow actors.

So many grew round me, through me,

from my self, as it were.

I became a channel, unleashing a force

called man.

Did not the others crowding in, distort

the man that I am?

Being each of them, always imperfect,

myself to myself too near,

he who survives in me, can he ever

look at himself without fear?

—“Actor”

In the fall of 1938, Wojtyla enrolled at Kraków’s Jagiellonian University, where his primary studies were literature and philosophy. However, the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939 changed everything, and Wojtyla was to write to Kotlarczyk: “Now life is waiting in line for bread, scavenging for sugar, and dreaming of coal and books.” It is reported that Wojtyla was in church for when Nazi bombs first fell on Poland, September 1, 1939. [If you look closely at the first three digits of that date, 9-1-1939 […]

With mercury we measure pain

as we measure the heat of bodies and air;

but this is not how to discover our limits—

you think you are the center of things.

If you could only grasp that you are not:

the center is He,

and He, too, finds no love—-

why don’t you see?

The human heart—what is it for?

Cosmic temperature. Heart. Mercury.

—“Girl Disappointed in Love”

Wojtyla continued his studies until the Nazis closed the university. The Nazis also closed libraries and only Germans were allowed to attend plays and concerts. A Pole could be shot for going to the theater. In November of 1940 Wojtyla took a job as a stone-cutter at a quarry near Kraków.

No, not just hands drooping with the hammer’s weight,

not the taut torso, muscles shaping their own style,

but thought informing his work,

deep, knotted in wrinkles on his brow,

and over his head, joined in a sharp arc, shoulders and veins vaulted.

—“Material”

Around this time, he met a tailor, Jan Tyranowski, who introduced him to St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross, “setting him on a deeper spiritual path.” And yet his passion for the theater remained undimmed: when Kotlarczyk came to Krakow in the summer of 1941, Wojtyla and his friends helped him start the underground Rhapsodic Theater, at the risk of their lives. Wojtyla wrote to his teacher and mentor that he wanted to build “a theater that will be a church where the national spirit will burn.” The Rhapsodic Theater “embraced the theatrical minimalism of long, static monologues and epic poems.” Wojtyla was also a budding playwright. At the age of 19 he had penned a blank verse biblical trilogy of David, Job and Jeremiah. By the age of 21 he was translating Greek tragedies and compiling patriotic Polish poetry. In addition to his more avant-garde work, Wojtyla also wrote a traditional play called “Our God’s Brother.”

It is reported that once when Wojtyla was clandestinely reciting an hour-long epic poem, Nazi megaphones began blaring forth news of a German victory, and he simply shouted out the remainder of the poem over the megaphones.

To illustrate the inherent dangers of daring to perform under the pince-nezed noses of the Nazis: members of the Rhapsodic Theater were later deported to Auschwitz.

Wojtyla “had never been an actor so much as an intoner” and the Rhapsodic Theater shed “all the clutter that gets between actors and their lines. Plot, action, even emotion, amounted to little more than pleasant diversions; the substance was all in what was spoken.”

Wojtyla also joined Jan Tyranowski’s clandestine underground religious circle, The Living Rosary.

In February of 1941, Wojtyla’s father, a devout Catholic, died at the age of 61. The pope has said that his father once told him, “I will not live long and would like to be certain before I die that you will commit yourself to God’s service.” Friends said that when his father died, Karol knelt for 12 hours in prayer at his father’s bedside. Soon thereafter, he withdrew from the theater to study for the priesthood, a decision that surprised many of his friends, who tried to convince him that his talent lay in the theater!

He later said, as pope, “At 20 I had already lost all the people I loved.”

The Eyes of Inspiration

Jagiellonian University reopened in 1942 and Wojtyla entered the faculty of theology with the intention of becoming a priest. In 1944, he attended an underground seminary at the residence of Archbishop Sapieha, who was soon to become Cardinal Sapieha. Around this time, Wojtyla was hit by a car while saving a man’s life. After the “liberation” of Kraków by Soviet forces, Wojtyla completed his studies and in 1946 was ordained as a priest by Cardinal Sapieha, in Sapieha’s private chapel. In his book, “A Gift and Mystery,” published 50 years later when he was Pope John Paul II, he said that he still feels a debt to friends who suffered “on the great altar of history” during World War II, while he studied in Sapieha’s clandestine seminary.

The greatness of work is inside man.

—“Material”

Wojtyla began doctoral studies in philosophy in 1947 and earned his doctorate in 1948 (he wrote his dissertation on The Problem of Faith in the Works of St. John of the Cross). He went on to earn a doctorate in moral theology from Jagiellonian University. In 1954 Wojtyla accepted a non-tenured professorship at the University of Lublin (the only Catholic university in the communist world) and would teach in various capacities for the next 20 years. Catholic News Service reports that “As a young priest, he was a favorite with students at Lublin University who flocked to his classes and joined him on camping, hiking and canoeing trips.” He also founded a service that dealt with marital problems, including family planning, alcoholism and physical abuse. TIME Magazine once called it “perhaps the most successful marriage institute in Christianity.”

He published more than 100 articles and several books, and in 1956 became a full professor at the Institute of Ethics in Lublin. According to Catholic News Service, “Father Wojtyla’s interest in outdoor activities remained strong, and younger companions called him ‘the eternal teen-ager.’ Groups of students regularly joined him for hiking, skiing, bicycling, camping and kayaking, accompanied by prayer, outdoor Masses and theological discussions.”

His first book, Love and Responsibility, was published in 1958. It advocated equality between married men and women and taught that sexuality between married couples was good: close to if not radical ideas for the church at the time. It was a bestseller.

Characteristically for the athletic, outdoors-loving Wojtyla, he was on a kayaking trip in 1958 when, at age 38, he was made auxiliary bishop of Kraków, the youngest bishop in Poland’s history.

In 1960 Wojtyla returned fleetingly to playwriting with the “dense and almost counterdramatic” play “The Jeweler’s Shop.” The play was performed several times on Polish radio, then resurfaced in the 1980s as a movie starring Burt Lancaster. Wojtyla, by then Pope John Paul II, received a screenwriting credit. According to a reviewer, the play “grapples … with two of his chief concerns as Pontiff—how to articulate true goodness and how to foster love. It is, it was, as the chorus councils in the first act: ‘words and hearts, words and hearts.'”

In 1963 he was promoted to archbishop and in 1967 he became Cardinal Wojtyla, at a time when the Polish Catholic church was being severely oppressed by Poland’s communist government. His appointment as cardinal by Pope Paul VI was welcomed by the government, but only because he was woefully underestimated.

Fear not. Man’s daily deeds have a wide span,

a strait riverbed can’t imprison them long.

—“Material”

The Polish secret police, the UB, had not been worried at Wojtyla’s promotion to archbishop, considering him a poet and apolitical dreamer. In 1967, the UB (the Polish secret police) analyzed Wojtyla as follows: “It can be said that Wojtyla is one of the few intellectuals in the Polish Episcopate. He deftly reconciles … traditional popular religiosity with intellectual Catholicism … he has not, so far, engaged in open anti-state activity. It seems that politics are his weaker suit; he is over-intellectualized … He lacks organizing and leadership qualities, and this is his weakness …”

[…]

In 1969 Wojtyla published The Acting Person, considered his principal academic work.

In 1978 Wojtyla became Pope John Paul II. He is said to have wept that day, October 16th, and to have put his head in his hands. Becoming Pope is “a clear cut off from one’s previous life, with no possible return,” one biographer wrote.

In 1979 John Paul II made his first trip to Poland as pope. Within a year, Polish tradesmen formed the now-famous Solidarity labor union, headed by Lech Walesa. The pope received Walesa at the Vatican in 1981.

Yet can the current unbind their full strength?

It is he who carries that strength in his hands:

the worker.

—“Material”

On May 13, 1981 John Paul II was shot and severely wounded in an attempted assassination by Mehmet Ali Agca.

In 1983 the pope returned to Poland for a second visit. Walesa, who later became the president of Poland, said John Paul II deserves “the greater credit” for the end of communism in Poland: “At the moment when the pope was elected, I think I had, at the most, 20 people that were around me and supported me — and there were 40 million Polish people in the country. However … a year after (the pope’s) visit to Poland, I had 10 million supporters and suddenly we had so many people willing to join the movement. … I compare this to the miracle of the multiplication of bread in the desert.”

Pope John Paul II died on April 2, 2005.

ΑΝΑΛΟΓΙΖΟΜΕΝΟΣ ΓΥΡΝΑΩ ΠΛΕΥΡΑ…

Αναλογιζόμενος την πατρίδα γυρνάω προς τη μεριά του δένδρου.

Ο δρόμος της γνώσης του καλού και του κακού μεγάλωνε.

Στις όχθες των ποταμών της γης μου μεγάλωνε μαζί μας για αιώνες.

Ρίζωνε στην εκκλησιά μας με της συνείδησης τις ρίζες.

Μεταφέραμε οπώρες που μας βάραιναν και πλουτίζαμε…

Νιώθαμε πόσο βαθιά σχίζονταν ο κορμός

Παρόλο που οι ρίζες φύτρωναν στην ίδια γη…

Η ιστορία με το επίπεδο των συμβάντων

Σκεπάζει την μάχη των συνειδήσεων.

Κι εκεί είναι που τρέμουν οι νίκες και οι ήττες

Η ιστορία δεν μπορεί να τα σκεπάσει αλλά τα φέρνει στο φως

ανακυκλούμενα…

POPE JOHN PAUL II

ΜΕΤΑΦΕΡΟΝΤΑΣ ΕΝΑ ΒΑΡΟΣ

Πλησιάζουμε όλοι στην ίδια γη τούτη των φτωχών

για αιώνες μεγαλωμένοι σε μια βαθιά άγνοια

ώσπου γίναμε αποκαΐδια συνείδησης

επίπεδη έρημος αθρώπινων συμβάντων

κι όμως εκεί φυτρώνουν οι ιστορικές ρίζες

βαθιά σκεπασμένες οι αιματοχυμένες ήττες

ανακυκλώνοντάς τες η εκκλησιά

φέρνει στο φως γνώσεις

μεταφυσικών δρόμων

κι όχθες μεγάλες συνειδησιακές

στις τραμπάλες καλού και κακού

απάνω μεγαλώσαμε

αναλογιζόμενοι πως τρέμουν

οι μνήμες νικημένες

γυρίσαμε από πατρίδα σε πατρίδα

αυτοεξόριστοι

μεταφέροντας ένα βάρος

μυθικών διωγμών

έτσι νιώσαμε παρόλα αυτά

σαν δένδρα που η ακινησία τους

κλαριοχτυπά βαριά

τον ερειπωμένο από δυνάμεις άνεμο

© M. KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2019

A Submerge Town

Jerzy Liebert (1904-1931)

Γεννήθηκε το 1904 στο Τσεστοχόβα. Συνδέθηκε από νωρίς με το περιβάλλον της καθολικής διανόησης (εκκλησίας). Τα έτη 1930-1931 νοσηλέυτηκε στο θεραπευτήριο Βορόχτσιε κι έχασε τη μάχη με το θάνατο το 1931, μόλις στα 27 του χρόνια.

ΓΛΥΚΟΦΕΓΓΟΣ

Περίσσιο σπλάχνος το ασημένιο σου κορμί

τους ανθρώπους συμφιλιώνει ο θεός

σε καιρό πολέμου

όταν φουντώνει μίσος πολύ μέσα στη καρδιά

τρέμουλο αστεριών και νυχτερίδας ο πυρετός

ολόιδια νυσταγμένη ψύχρα

ελαφροσύννεφο βάρος λευτερωμένου ουρανού

πέρα στους γαλαξίες

υπάρχει γλυκόφεγγος ο ποιητής

σαν ασπίδα μαχόμενης θλίψης

σύμπαν λευκαυγές

κατεβαίνει ως το ανοιχτό παραθύρι

κι ορμάει μέσα

θα πιει στους τάφους τη γη

ρουφώντας σκόνη αναγεννά όλους μας

εκεί απάνω

© M. KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2019

Νύχτα κι όταν η ροδαυγή πάνω απ’ τα άστέρια κατεβαίνει

Κι η ψύχρα σα νυχτερίδα νυσταγμένη απ’ το ανοιχτό παράθυρο ορμάει

Σκέφτομαι πως είμαι πια σε πάχνη που θα με πιει το σύμπαν

Κι όμως η γη δε με ρουφάει κι ούτε με αναγεννά…

Κι ότι εκεί, πάνω απ’ τα σύμπαντα κι από τους γαλαξίες

Και πάνω απ’ το γλυκόφεγγο το λυκαυγές που σαν ασπίδα

Υπάρχει η πατρίδα μου που νοσταλγώ και μάχομαι

Με τη θλίψη που φουντώνει στη καρδιά και την αιώνια αγάπη.

Μα υπάρχει κι ο θεός π’ όλα τα ισσοροπεί και συμφιλιώνει

Της καρδιάς το τρέμουλο με του καιρού το γύρισμα

Σαν το σύννεφο απ’ το βάρος των αστεριών και το περίσσιο ασήμι

Που απ’ τη γη, το σώμα μου θα λευτερώσει

JERZY LIEBERT

ΣΤΙΣ ΑΚΡΕΣ ΤΩΝ ΟΝΕΙΡΩΝ

Νυχτερινά βλέφαρα

μη μπορώντας να τ’ ανοίξει ο θάνατος

αφέθηκε σ’ ένα μαύρο σιωπηλό ποτάμι

όπου ρέει η γαλάζια ομίχλη

βήμα όνειρο δεξιόστροφο

γκρίζες οι φωνές του ουρανού

μιας γκρίζας φωνής η γη

σηκώθηκα άγνωστος ακόμη στη ζωή

ν’ ακουμπίσω ανέφικτα βρέφη

που ‘χαν αγέννητο βλέμμα

πευκοανάσαινα φτερουγίσιες μυρωδιές

πεταλούδας

αργοσαλεύει στις άκρες των ονείρων ο ύπνος μου

παράθυρα τοιχοχτισμένα βλέμματα

ακουμπάει εκεί η νύχτα

ηχεί ο χρόνος παρθένος

οι ώρες κρατάνε στα δάχτυλα μαστίγια

τρίτου χεριού στενόχωρα αγγίγματα

βαθιές πληγές ψυχοκάρδια μοίρας

δεν φεύγουν τόσο εύκολα

οι νεκροί από πάνω μας

© M. KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2019

Portrait (Symbolic) of Copernicus

Jozef Czechowicz (1903-1939)

Czechowicz was born, created his works and died in Lublin. His tragic death is reminded by the statue of the poet in Plac Czechowicza. The poet is seen as a nostalgic and catastrophic writer, nevertheless, he was also the leader of Lublin avantgarde and bohemia. The author of Poemat o mieście Lublinie (A Poem about Lublin) was a modern poet, whose works had strong influence on the next generations. So far, his output in the fields of drama, journalism, translation, photography and pedagogy has remained unnoticed. Czechowicz – regionalist has also been forgotten. Above all, this underestimated mistifier, genius and visioner, who lived a short but fascinating life, left – despite his early death – a very rich collection of works.

The “Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre” Centre organises events to commemorate Józef Czechowicz’s birth and death, every year there is also a public reading of Poemat o mieście Lublinie (A Poem about Lublin) combined with a walk around the places described in it. Special papers contributed to the poet’s work are issued here as well.

Place and Date of Birth

Józef Czechowicz was born on 15th March, 1903 in a basement flat in Kapucyńska 3 St in Lublin. The building no longer exists, it used to be situated in the back of what today is Galeria Centrum (Centrum Department Store).

Czechowicz’s Family

Czechowicz was born in a poor family. His father was a bank janitor, and his mother a washerwoman. The poet soon lost all his close relations. This fact leaves a visible mark in his works. The poet’s older brother, Stanisław Czechowicz, a journalist with a vivid mind and brisk style, died of tuberculosis in 1925, at the age of 26.

He was buried in the Lublin cemetary at Lipowa St. The poet’s younger brother, Janek, whom Józef Czechowicz did not even remember, had been buried there as well in 1903. His father, Paweł Czechowicz, died in 1912, suffering from serious mental illness. Małgorzata Czechowicz, Józef Czechowicz’s mother, to whom his poems were often dedicated, died in April 1936. His sister, Katarzyna, died in 1958. Her family live in the Ukraine today.

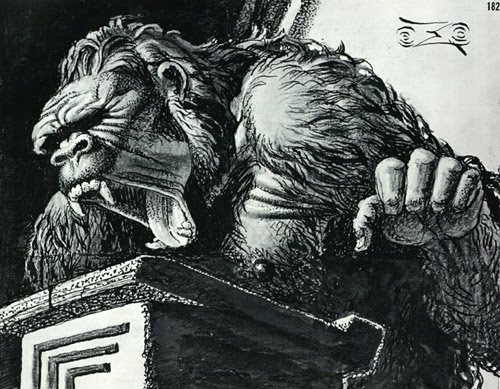

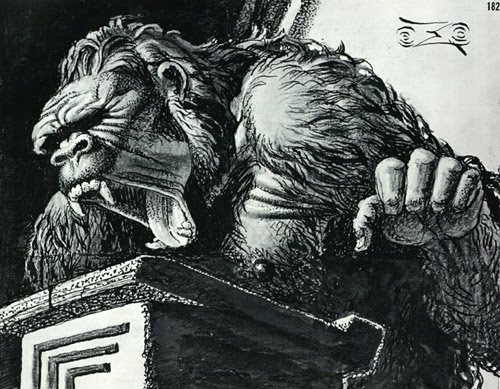

Orangutang With a Chain

Czechowicz – Pedagogue

A young graduate, Czechowicz was employed as a teacher in Słobódka. In the years 1923–1924 he taught in Włodzimierz Wołyński.

Since 1926 he also worked in a special school in Lublin, where he became a manager. He edited magazines for children: “Płomyk” and “Płomyczek”. He was also active in “Głos Nauczycielski” (“Teacher’s Voice”).

Czechowicz’s friends remember him as a person who treated his teacher’s profession seriously, taking notes, observing his pupils, which can be seen in entries in his diary.

The “Reflektor” Group and Magazine

After meeting the creators of the ‘Reflektor’ – Konrad Bielski and Wacław Gralewski – in the summer of 1922, Czechowicz sent them samples of his literary works and corresponded with them. The materials sent included the Opowieść o papierowej koronie (A Story of a Paper Crown). While choosing texts for the first issue of the “Reflektor”, the young editors resigned from Czechowicz’s poetry, but decided to use this story. Later, they recognized the value of his poetry and started to print first poems in “Reflektor” – for example the one titled Na wsi (In the country). After entering these circles, Czechowicz also became acquainted with Czesław Bobrowski and Stanisław Grędziński. The group of literates used to meet most often in the office of “Express Lubelski” (“Lublin Express”), in Gralewski’s editing room. It was an important period in the young artist’s life, whose poetic breakthrough could be seen when he worked on the second issue of the “Reflektor” in 1925.

The Avantgarde Leader

In addition to restaurants, pubs and artists’ flats, where the Lublin bohemia used to meet, in pre-war Lublin there were several places which gained significance due to the presence of young artists and literates. They were Lublin “literary salons”: Mieczysław Biernacki’s place, Franciszka Arnsztajnowa’s place at Złota 2 St , rev. Ludwik Zalewski’s villa at Graniczna 1c (now 9) St. Other, worth mentioning for their atmosphere and legend, are so called “ojciec Grudzień’s” pub and Edward Hartwig’s studio at Narutowicza St. Czechowicz, together with Łobodowski, was the bohemia leader. In 1934 he organized the famous “Avangarda Warsaw raid”, which was an expression of rebellion against the “Wiadomości Literackie” (“Literary News”) and the “Skamander” poetical group.

The Poet in Warsaw

In 1933 Czechowicz, author of three poetry tomes, moved to Warsaw. When he worked in Związek Nauczycielstwa Polskiego (Polish Teacher’s Association) he used to help many colleagues-authors – he supported printing their works or helped them financially. Czechowicz took care of a group of poets living at Dobra 9 St.: Henryk Domiński, Wacław Mrozowski and Bronisław Ludwik Michalski. When he lived in Warsaw, the poet made friends with, among others, Czesław Miłosz, Anna Świrszczyńska, Stanisław Piętak, Paweł Hertz. During his studies he got acquainted with the circles of poetic groups “Kwadryga” and “Meteor”. In Warsaw he also edited the famous magazine for children, “Płomyczek”, where he published his works under different names.

Blessing the New Citizen

Czechowicz Bibliophile

According to memories of numerous people, in his home library Czechowicz had books on Lublin, which proves his interest in the past and culture of the city. The poet often visited Lublin bookshops and libraries to watch and read books.

In 1926 he was one of the founders of Lubelskie Towarzystwo Miłośników Książek (Lublin Book Lovers’ Association). Naturally, the most desirable places to meet for people from such circles were bookshops, including the one run by a legendary Lublin bookseller, Franciszek Raczkowski.

As a member of the Lublin Book Lover’s Society, Czechowicz took part in meetings organized, among others, in Museum at Narutowicza 4 St. When he was a secretary of LTMK, he wrote a poem Z kroniki bibliofilów lubelskich (From the chronicles of Lublin bibliophiles) (1931).

He wrote a few articles concerning popularizing reading and love of beautiful books, which were printed in “Express Lubelski”, “Kurier Lubelski” and “Ziemia Lubelska”.

In 1932 the poet was one of the founders of Związek Literatów w Lublinie (Writers’ Association in Lublin).

In addition to that, Józef Czechowicz worked with rev. Ludwik Zalewski on publishing an anthology of contemporary Lublin poetry which was published in June, 1939.

Czechowicz – Photographer

Czechowicz’s collection of photos includes pictures from 1930s and is an important document concerning old Lublin and Lublin Region. The poet also took many photos when he was on a scholarship in France. Czechowicz was a friend of a well-known Lublin photographer, Edward Hartwig, who remembered the poet’s visits in his atelier. On photos of Lublin made by Czechowicz we can see, among others,The Grodzka and Krakowska Gates, The Old Town with its streets and views of the Jewish district which does not exist today.

Czechowicz and the Cinema

Czechowicz was the first Lublin journalist so greatly involved in cinema industry – he wrote reviews, advertised films and criticized conditions in Lublin cinemas. He used to write under different pen names, such as “Kinoman” (“Cinema Fan”).

In “Kurier Lubelski”, of which he was the editor-in-chief and publisher, from January to July 1932 we can find a Na srebrnym ekranie (On silver screen) section, contributed to film issues. Probably it was written by the poet himself.

Czechowicz and Theatre

The poet wrote few dramas, published in “Pion”: Czasu jutrzennego (Of Tomorrow Time), Jasne miecze (Bright Swords) and Obraz (The Picture). First of them was staged in Warsaw in Teatr Nowy in 1939. A small number of dramas is the result of the fact that the poet turned to this genre relatively late. However, in some of his previous works one can find a specific form of introducing dialogues and drama elements in the form of poems (Opowieść o papierowej koronie, Dwugłos, eros i psyche, elegia żalu, Rozmowa czyli kochankowie). His drama is a poetic drama, close to symbolic theatre.

Czechowicz also wrote theatrical reviews. Particularly, a lot of texts on theater were published in “Kurier Lubelski” in 1932, when he was its editor. Under the pen name Recenzent (Reviev Author) he wrote many reviews of plays in Lublin Theatre, close to which he had grown up, as the house on Kapucyńska St was situated near the Theatre on Narutowicza St. (then Namiestnikowska).

In the years 1927–1928 Czechowicz was a member of Komisja Teatralna (Theatrical Committee), set up in 1921 by the Lublin Magistrate as an opinion-giving body for the local authorities. Other members of the Committee were: Wacław Gralewski, rev. Ludwik Zalewski, Konrad Bielski, Feliks Araszkiewicz.

A close friend of Czechowicz was a thetre man, director, Wilam Horzyca.

“Bybyots,” a 1939 graphite and ink on paper

Tragic Death

When the war broke out Czechowicz left Warsaw and returned to Lublin. He died in his hometown bombardment on 9th September 1939 between 9 a.m. and 10 a.m. It happened at Ostrowska barber’s shop which was situated in a house at Krakowskie Przedmieście 46 St.

THEATRE NN PL

Mermaid Fountain

Για τον θάνατο τίποτα πια δεν ξέρω

Στα μαύρα παράθυρα και στα βλέφαρα

Χτυπάει με τις φτερούγες του τις πεταλούδες μυρίζει πευκοανάσα

Και μ’ ακουμπάει κάθε νύχτα μ’ όνειρα, πίσω από το σιωπηλό ποτάμι

Εκεί που η ομίχλη βήμα με βήμα αργοσαλεύει στη άραχλη άκρια…

Κρατάει στη γαλάζια κασέλα το ακόρτ, μη μπορώντας να την ανοίξει

Η ζωή είναι βραχύ όνειρο

Ηχεί στενάχωρα η φωνή από αριστερά

Η ζωή μικρού ονείρου, ανέφικτου είναι το τρίτο

Σηκώνεται στο γκρίζο ουρανό

η ομίχλη απ’ άγνωστη μορφή

κι ο χρόνος και η παρθένα γη.

Ω, γιατί το βλέμμα σου δε φεύγει

Κάτω απ’ τα παράθυρα εκεί στο τραπέζι…

Από την ώρα που γεννήθηκα, από τα νεκρά χέρια του Τσέχοβιτς.

JOSEF CZECHOWICZ

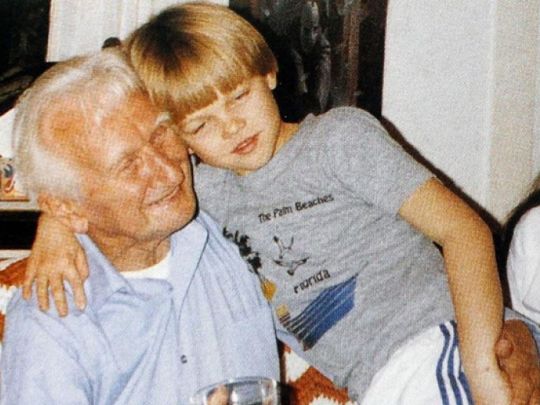

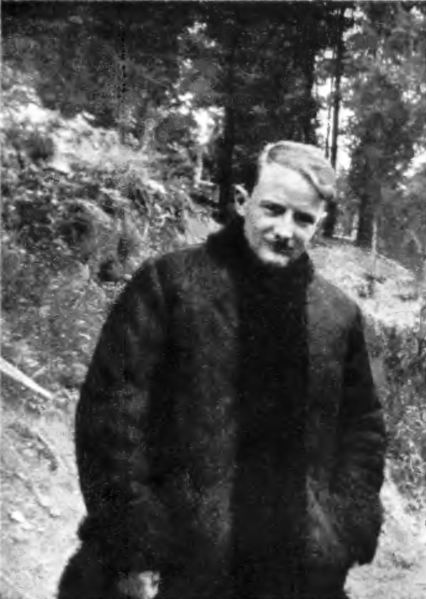

With the young Leonardo di Caprio

In the poem about Czechowicz from The Separate Notebook cycle, the subject acts in a yet different, m ore ritual manner. Is there a way to communicate with the dead across the boundary of death? T here is, but an insufficient one – answers the poem in several verses of different tonality. The colloquialism of some of them aim s to eliminate or reduce the distance between the living and the dead (“Yet I presume you have some trace of interest, at least as to your own continued stay among the living.” (382)). The high tone of others clearly emphasizes the poetic character of the situation: “you appear now on this other continent, in the sudden lightning of your afterlife”). Czechowicz is presented in the uniform of a soldier from the year 1920.

From shit-houses in the yeard, tomatoes on the windowsill, vapor over washtubs, greasy checkered notebooks – How could that modest music for young voices soar, transform ing the dark fields below ?…Set apart by a flaw in your blood, you knew about Fate; but only the chant endures, nobody knows about your sorrow (383).

Czechowicz’s poetry directs the reader (or the listener) not to its m aker but to a different reality that he created or revealed. N ot a biographical, historical, social, but a m etahistorical, metaphysical one: http://rcin.org.pl Łukasiewicz Poet on poets W here are you behind your words, and all who are silent, and a State now silent though it once existed (383).

Poet on poets Jacek Łukasiewicz Przeł. Anna Warso

Head of Meteorphy, 1972, graphite and ink on paper

[…]

Czechowicz could not wholly accept the fulfilment of experience in a symbol; he could not remain hidden for long behind the mask of a persona. What attracts one to his poetry is precisely the artist’s courage in stumbling occasionally over the props of the chosen form; a faux pas of that sort pushes a great artist to a discovery beyond theory and his own practice. Czechowicz in his final phase seems to have the ‘stumbling’ courage of genius; he makes poetic discoveries almost by chance, but each step of his progress towards some new discovery is imprinted on a sentence with his characteristic exactitude. The passage just quoted would not strike us by its truthful tone if it were not preceded by this opening chord:

glow? ktora siwieje a swieci jak swiecznik

kiedy srebrne pasemka wiatrow przefruwajg

niose po dnach uliczek

jaskolki nadrzeczne

swiergoca to malo

idzze (zal)

(my head which is greying but shines like a chandelier / when the silver strands of wind fly over / I carry along the hollow streets / the swallows by the river /

[…]

Leśmian and Czechowicz: Two Uncommitted Poets

Author(s): Jerzy Pietrkiewicz

Source: The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 37, No. 89 (Jun., 1959), pp. 336-347

Published by: the Modern Humanities Research Association and University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies

Mieczyslaw Jastrun (1903-1983)

(Original surname Agatstein; 1903–1983), poet and essayist. Mieczysław Jastrun studied German and Polish philology and subsequently worked as a high-school teacher, publishing poetry in literary journals. After World War II, which he survived on the so-called Aryan side in Warsaw, Jastrun joined the Communist Party and edited the government-sponsored journal Kuźnica (1945–1949). After breaking with the party in 1957, he belonged to the group of writers actively defending freedom of speech.

Jastrun’s publications include the volumes of poetry Spotkanie w czasie (Meeting in Time; 1929), Dzieje nieostygłe (History Is Cooling Down; 1935), Strumień i milczenie (Stream and Silence; 1937), Godzina strzeżona (lit., “Protected Hour,” a Polish translation of a Hebrew term for the times when God hears one’s prayers; 1944), Rzecz ludzka (A Human Matter; 1946), Poemat o mowie polskiej (Poem about the Polish Language; 1952), Gorący popiół (Hot Ashes; 1956), and Punkty świecące (Shining Points; 1980). He also wrote the novels Mickiewicz (1949), Poeta i dworzanin (Poet and Courtier; 1954), and Piękna choroba (Beautiful Illness; 1961); the collections of essays Mit śródziemnomorski (Mediterranean Myth; 1962) and Poezja i rzeczywistość (Poetry and Reality; 1965); and the memoirs Smuga światła (Streak of Light; 1983) and Dziennik 1955–1981 (Diary 1955–1981; 2002). Jastrun also translated German, Russian, and French literature.

While neo-symbolism and a catastrophic worldview permeated his early poetry, Jastrun’s first postwar works echo the new historical experiences of socialism; he later returned to classic Polish and Mediterranean traditions. Except for a handful of poems inspired by the Holocaust (according to Artur Sandauer, “confessions of a Marrano hiding on the Aryan side”), Jastrun shunned Jewish themes. In 1944 a few poems, “Pieśń żydowskiego chłopca” (Song of a Jewish Boy), “Żydzi” (Jews), and “Poległym” (To the Fallen) appeared in the underground publication Z otchłani (From the Abyss) and in Godzina strzeżona. In his diaries Jastrun analyzes his own survival, wartime Polish–Jewish relations, and the issue of assimilation.

YIVO

Mieczysław Jastrun was born Mojsze Agatstein in 1903 in Korolowka, Austria-Hungary (now Ukraine), and died in 1983 in Warsaw, Poland. A lyric poet and essayist of Jewish origin, he survived the terrible years of the Nazi occupation in Poland, and published a dozen volumes of poetry during his lifetime, including A Human Matter, A Meeting in Time, Protected Hour, and Memorials. He concerned himself most often with subjects of philosophy and morality and shunned Jewish themes in his poetry (with the exception of a few poems). However, as a poet who published his poems in resistance periodicals, he couldn’t turn his back on the horrors of the genocide, nor was he able to escape historical necessity and despair in even his most mystical writings. Jastrun is considered to be one of the most important Polish poets of the years between the two world wars. He translated French, Russian, and German poets (including Rilke) into Polish. His work is included in Postwar Polish Poetry: An Anthology, edited by Czesław Miłosz.

LIGHT FROM ANOTHER WORLD

One life has passed

I passed over what hurt the most

in silence

I forgot about the changes

they grew pale like stars at dawn

shining in leafless trees

Light from another world

embraced me

A hyacinth’s keen scent

And nothing- like a stone thrown into water

nothing- like water turned to stone

frozen by the morning cold

One life has passed

I passed over silence in silence

I forgot

on this planet where it was so hard

to square endless otherness

with my own brief time

A steep staircase opened beneath me

leading to a tunnel underground

where letters

on the wall spelled

the saving phrase: “Way Out.”

(Translated by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh)

Copernicus Capturing the Sun, 1972, graphite and ink on paper

ΑΠΟ ΤΟΝ ΑΛΛΟ ΚΟΣΜΟ ΦΩΣ

Πέρασε μια ζωή

Αποσιώπησα αυτό που με πόνεσε

Πιο πολύ απ’ όλα

Τις ανακατατάξεις ξέχασα

Χλόμιασαν σαν τα τελευταία αστέρια της αυγής

Που φωτίζουν τα δίχως φύλλα δέντρα

Από τον άλλο κόσμο φως

Που μ’ αγκάλιασε

Η πλημμύρα μυρωδιά του υάκινθου

Και τίποτ’ άλλο-σαν πέτρα στο νερό

Και τίποτα-σαν νερό στη πέτρα

Κομμένη στην πρωινή ψύχρα

Πέρασε μια ζωή

Απροσπέλαστη σιωπή

Ξέχασα σ’ αυτό το πλανήτη

Που τόσο δύσκολα ήτανε

Να συμφιλιώσεις τον άπειρο χρόνο

Με την απέραντη σιωπή

Άνοιξαν τα απότομα σκαλοπάτια

Στην υπόγεια σήραγγα

Όπου στο τοίχο γραμμένη υπήρχε

Μια απελευθερωμένη λέξη:

Έξοδος!

MIECZYSLAW JASTRUN

ΥΠΟΓΕΙΟ ΦΩΣ

Η έξοδος προς την πρωινή ψύχρα

μιας πέτρας η απελευθέρωση και τίποτα άλλο

λέξεις άγραφτης σιωπής

ήταν δύσκολες πολύ

απέναντί σου ανοίγονταν η μυρωδιά

από τα απέραντα σκαλοπάτια

απροσπέλαστη πλημμύρα νερού

κομμένου στα δυό

σε αποσιώπησε η ζωή

πόνεσες, χλώμιασες ώσπου ξέχασες

όλες τούτες οι απότομες ανακατατάξεις

ο πλανήτης του φωτεινού υάκινθου

η απειροσύνη

υπόγειο φως

κόσμου γραμμένου στους τοίχους

εκεί κάτω υπάρχει κάποια σήραγγα συμφιλίωσης

όπου οι τελευταίοι θνητοί της αυγής

ήταν αγκαλιασμένοι

πεφταστέρια αθανασίας

© M. KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2019

from MemorialsMieczysław Jastrun

Grains

Sunset glows in the wheat, oats and rye,

crops multiplying in the fields.

We traveled

the world, believing in the earth.

Of the corn, we asked

who? who?

In the silence of impassibility

the ears bend toward the ground

like questions rising up.

Do you go where the wheat is?

God breathes in the grain, gives us our bread,

but nothing can alleviate our poverty.

Nothing can give us back our home.

We live in a time of false piety

in which money rules

like King Midas petrified

in a paradise of gold.

Why

Under the sky where the butchers’ knives

stripped the bloody skin,

I saw those murdered

between the knees of God.

For years, in our animal furs,

we survived the huge blinding winters

and dust storms of wheat

in August.

No one remembers anything.

We shifted from foot to foot

waiting in long lines

for our deaths.

Only one of us asked,

Why does God kill us?

Why did he give up on his children

after the Resurrection?

Only one of us waiting

for him to fall

again from the cross cried,

“Why has the world forsaken us?”

translated from the Polish by Dzvinia Orlowsky and Jeff Friedman

Like Ronald Reagan, Wojtyla was an actor. And a dark-haired, ruggedly handsome actor at that, as his picture to the left attests. In the early 1930’s, he met Mieczyslaw Kotlarczyk, who would teach him (and isn’t it an interesting “method” for a future Pope!) “the Living Word,” a style of performance rooted in Polish songs and Polish poetry as sung and recited after dinner in country manor houses. In Pope John Paul II: The Life of Karol Wojtyla, Fr. Mieczyslaw Malinski recounts that it was during this time that Wojtyla first came to the attention of the Archbishop of Kraków, Adamo Stefano Sapieha. Sapieha was visiting his school and young Wojtyla gave the welcoming speech. Impressed, Sapieha asked whether Karol intended to become a priest. A priest replied that his interests seemed to lie with the theater, “an answer which disappointed the archbishop!” To make matters perhaps worse, Wojtyla later joined an experimental theater group known as “Studio 38.” His love of the theater persisted, because later as a cardinal, he celebrated holidays with Krakow actors.

Like Ronald Reagan, Wojtyla was an actor. And a dark-haired, ruggedly handsome actor at that, as his picture to the left attests. In the early 1930’s, he met Mieczyslaw Kotlarczyk, who would teach him (and isn’t it an interesting “method” for a future Pope!) “the Living Word,” a style of performance rooted in Polish songs and Polish poetry as sung and recited after dinner in country manor houses. In Pope John Paul II: The Life of Karol Wojtyla, Fr. Mieczyslaw Malinski recounts that it was during this time that Wojtyla first came to the attention of the Archbishop of Kraków, Adamo Stefano Sapieha. Sapieha was visiting his school and young Wojtyla gave the welcoming speech. Impressed, Sapieha asked whether Karol intended to become a priest. A priest replied that his interests seemed to lie with the theater, “an answer which disappointed the archbishop!” To make matters perhaps worse, Wojtyla later joined an experimental theater group known as “Studio 38.” His love of the theater persisted, because later as a cardinal, he celebrated holidays with Krakow actors.

Recent Comments