YOU WILL NEVER BE ALONE WITH A POET IN YOUR POCKET I

YOU WILL NEVER BE ALONE WITH A POET IN YOUR POCKET, JOHN ADAMS

ESPECIALLY A GREEK ONE, MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS

THIS WEBPAGE OF HELLENIC POETRY IS DEDICATED TO THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD

THE UNIQUE POUKA

Bewildered Wilderness

Man is an animal that has gone wild. And this bewildered wilderness, has been wrongly termed by this same animal -which is totally out of control- A CIVILIZED SOCIETY.

MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2017

“The Hunted”

POETRY IS A TREE, A TALL ONE, IN THE MIDDLE OF THE DESERT OF THIS BEWILDERED WILDERNESS, WHERE THE LITLLE MAN, THE SCARED MAN, THE HUNTED MAN, CAN CLIMB, AND BE SAFE, AT LEAST FOR A WHILE…

MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2017

Η ΚΒΑΝΤΙΚΗ ΥΠΟΣΤΑΣΗ ΤΗΣ ΨΥΧΗΣ

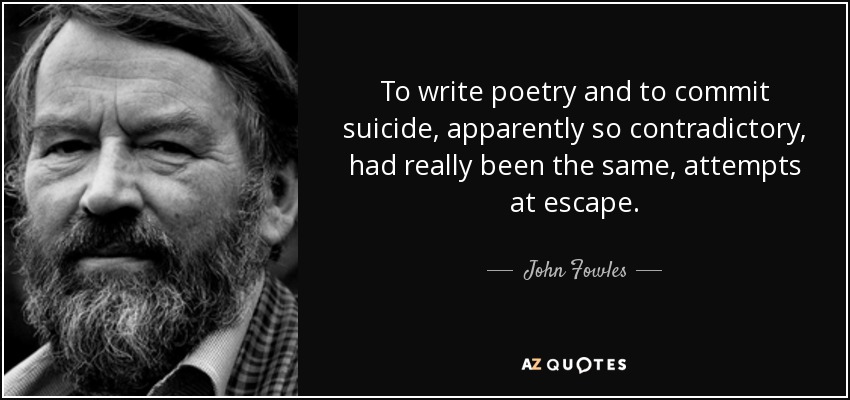

In the course of one week in 1977, the writer John Fowles received a total of half a million dollars as an advance for his novel Daniel Martin and in option money for the film version of his 1969 best-seller The French Lieutenant’s Woman. […] For two decades, Fowles was unique among English writers in combining literary sensibility with mass popularity.

He was born in 1926, at Leigh-on-Sea, in Essex. […]

[…] There he could express his passion for the natural world. This enthusiasm for natural history had been nurtured early, thanks to an uncle who was an entomologist and two cousins, one of whom was an authority on ants.

For the last year of the Second World War Fowles attended Edinburgh University, then did 18 months’ military service as a lieutenant in the Royal Marines, an experience he loathed. It was there that he began keeping a journal. In 1947 he resumed his studies at New College, Oxford, where he read German and French. Here he dreamed of “enduring literary fame” and showed himself to be both an intellectual snob and a Francophile. […]

Then, late in 1951, fatefully, he took up a teaching job for two years at the Anargyrios College on the Greek island of Spetsai. The experience changed his life. There he fell for Elizabeth Christy, the wife of a fellow teacher.

in London in 1953, Elizabeth left her husband and, reluctantly, her two-year-old daughter, Anna, for Fowles. However, whilst she was living in poverty in London, Fowles was working at a finishing school in Hertfordshire where, over the next year, he had relationships with two pupils in quick succession (one of whom became the model for Lily in The Magus). At the same time, he was telling Elizabeth that, though he wanted a relationship with her, he did not want to be responsible for her daughter. “It would not even be enough to leave Anna,” he said. “You would have to leave the guilt behind as well.”

John Fowles and Elizabeth Christy married in April 1954. Anna stayed with her father. The loss to Elizabeth was made more poignant by the fact that she and Fowles could not have children of their own. Over the years that followed, mother and daughter did meet on occasion and eventually forged a meaningful relationship.

Fowles continued his teaching career in north London at St Godric’s College. He taught there until 1963, ultimately as head of department, but was writing all the time. In 1953 he had submitted a novel about Greece – “An Island and Greece” – to an agent (Paul Scott, later a successful novelist himself), but it had been rejected. This was not a prototype for The Magus. He had been working on that, too, as an overtly supernatural work in the style of The Turn of the Screw.

The Magus was first called “The Godgame”. Both narrative and mood, as Fowles later wrote “went through countless transformations” over the years. All versions shared the same basic plot, however, in which a young English schoolmaster, Nicholas Urfe, ditches his girlfriend (based on Elizabeth) and goes to teach on a lonely Greek island. There he meets the wealthy, mysterious Maurice Conchis and is drawn into the old man’s Godgames through his infatuation with an alluring girl. (Originally, he had intended to make Conchis a woman, but had a failure of nerve.) Fowles was strongly influenced when writing The Magus by a now little-known novel, Richard Jefferies’s Bevis (1882), and, more overtly, by Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes (1913) – its sadness for a lost magical world chimed in with his own feelings about leaving Spetsai.

Fowles had put “The Godgame” to one side and was working on “Tessera”, a novel about two people who have fallen in love with Greece and are living in permanent exile from it, when he had the idea for a short potboiler. (He had about nine other unpublished novels in his drawer by this time too.)

He wrote the first draft of The Collector, in which a clerk with a passion for collecting butterflies kidnaps an art student he desires, in four weeks. (Fowles later confessed that a favourite fantasy of his involved “imprisoning women underground”.) It was published in 1963 to almost unanimous critical acclaim and turned two years later into a commercially successful film starring Terence Stamp. Fowles’s experiences when he went briefly to Hollywood to work on the script later formed part of the background to Daniel Martin.

Fowles was catapulted to fame and fortune – the film rights to The Magus were sold before he had even finished it. In 1964 he began collating and rewriting all the previous drafts of The Magus. A virtuoso piece of storytelling, it was published in 1965 and, despite critical reservations, was an immediate popular success, especially with students. He wrote in the foreword to a revised version published in 1977:

I now know the generation whose mind it most attracts. And that it must always substantially remain a novel of adolescence written by a retarded adolescent.

The film that followed, in 1968, starring Michael Caine and Anthony Quinn, was notoriously bad and rendered even more infamous by a Woody Allen joke: “If I had to live my life again, I’d do everything the same, except that I wouldn’t see The Magus.”

By then Fowles and his wife were living in Dorset, first at Underhill Farm, a mile and a half along the coast from Lyme Regis, with a spectacular view out to sea. Returning from a trip to London one day, they found that one of their fields and a number of trees had disappeared; they had slipped into the sea. Elizabeth hated Dorset – she was lonely and depressed in the winters. Fowles had wanted to move to France – his study of French had helped form him and he always thought of himself as a European rather than an English novelist – but instead they bought Bunter’s Castle, a roomy house in Lyme Regis with a late 18th-century façade, dubious past reputation and an enormous walled, wooded garden. They moved there in 1968.

Fowles later said of Elizabeth: “She was working-class, really, the intelligent, emancipated working class,” he once explained:

I’m a middle-class child. I was brought up under all the wrong lights and all the wrong principles and it was Elizabeth who taught me what nonsense all that is.

She was also his muse – the inspiration for pretty much all the unknowable, enigmatic women in his fiction – and a ruthless editor of his work. She made cuts and drastic changes, was derisive of his attempts at playwriting and changed the endings of his novels. On one occasion she said he had a “Woman’s Own style”. For better or worse, it was she who insisted on the two alternative endings for Fowles’s most successful novel, The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969).

That novel started with a dream – Fowles firmly believed in the power of the writer’s unconscious for creating fiction: “You should give yourself to your imagination.” He often recorded his dreams. A recurring one he had on the threshold of sleep was that of a woman standing on the Cobb (Lyme’s vast manmade breakwater which could be clearly seen from his garden). He didn’t know why she was there so he wrote the novel to find out. She became the anti-heroine Sarah Woodruff, a governess isolated by the local community for her rumoured former liaison with a French naval officer. The French Lieutenant’s Woman did as well as its predecessor, a success compounded three years later by an accomplished film version, starring Meryl Streep, scripted by Harold Pinter and nominated for five Oscars.

[….]

I’ve never been able to finish a novel in my life. I always have ideas for endings, think I’ve got the whole thing locked up, then – bugger me – along comes some last-minute idea.

As a result, Fowles was famously reluctant to let go of his novels at all. One of his publishers suggested he was like a miser, counting over his gold.

By 1970, Elizabeth had become so forceful in her criticisms – particularly of a thriller, The Devices, that Fowles had just written – that her husband never invited her to comment on his work in progress again. Over the next two decades Fowles published only four works of fiction: The Ebony Tower (1974), Daniel Martin (1977), Mantissa (1982), and A Maggot (1985). He used to talk of novels being “brewed”:

It means you write the idea or the main part of it in a given period. Then you have to let it lie, like a good beer, and it gathers strength, gathers flavour, all the rest of it, over time.

[…]

In Daniel Martin, the central character is involved with two women, one young, one old. The older woman was Elizabeth, although she didn’t realise it. “When Elizabeth first read it, she said she hated that woman,” he recalled.

[…]

In 1984 he had the idea for “In Hellugula”, about a woman who at the start of the novel is trapped in a foreign country when the Second World War breaks out. “I’ve never been able to work out what my female characters are likely to do,” he said later. He worked on the novel on and off – he admitted he was “atrociously lazy” – until, in 1989, he suffered a stroke that left him frail and slow in speech. The novel has never been published.

His wife, meanwhile, was suffering frequent bouts of depression and escaping to London with increasing frequency. Then, in 1990, Elizabeth died of cancer only a week after it had been diagnosed. Her death left him bereft. Fowles didn’t write for a year. Ill-health dogged him thereafter, although, with the help of his stepdaughter and several other women whose presence inspired him, he was able eventually to resume writing.

[…]

In 1998 he published a collection of essays, Wormholes. For the previous eight years he had engaged in a number of relationships with much younger women but that year he married a family friend, Sarah Smith, daughter of Major Peter Smith, founder Secretary of the Jockeys Association. She took charge of him, breaking contact for him with some of his women friends and caring for him through illness. “I never thought I would find someone who weighed as much with me as my first wife.”

[…]

Fowles was becoming increasingly frail – he had had a stroke in 1988 and heart surgery. Almost since his move to Lyme Regis, he had been reclusive, at odds with the modern world and jealous of his privacy. It seems ironic then that his last work to appear was the most private – his Journals, the first volume published in 2003, the second last week. He said:

I just hope they give a detailed picture of what I have been . . . I do not begin to understand my own personality myself.

INDEPENDENT

The Hope of the Resurrection by Vachel Lindsay

Though I have watched so many mourners weep O’er the real dead, in dull earth laid asleep— Those dead seemed but the shadows of my days That passed and left me in the sun’s bright rays. Now though you go on smiling in the sun Our love is slain, and love and you were one. You are the first, you I have known so long, Whose death was deadly, a tremendous wrong. Therefore I seek the faith that sets it right Amid the lilies and the candle-light. I think on Heaven, for in that air so dear We two may meet, confused and parted here. Ah, when man’s dearest dies,’tis then he goes To that old balm that heals the centuries’ woes. Then Christ’s wild cry in all the streets is rife:— “I am the Resurrection and the Life.”

FAMOUSPOETSANDPOEMS

|

|

|

The Congo Full Audiobook by Vachel LINDSAY by Poetry Fiction

In Memory of a Child by Vachel Lindsay

I

The angels guide him now, And watch his curly head, And lead him in their games, The little boy we led.

II

He cannot come to harm, He knows more than we know, His light is brighter far Than daytime here below.

III

His path leads on and on, Through pleasant lawns and flowers, His brown eyes open wide At grass more green than ours.

IV

With playmates like himself, The shining boy will sing, Exploring wondrous woods, Sweet with eternal spring.

V

Yet, he is lost to us, Far is his path of gold, Far does the city seem, Lonely our hearts and old.

FAMOUSPOETSANDPOEMS

VACHEL LINDSAY’S SPRINGFIELD -1977

Drying Their Wings by Vachel Lindsay

What the Carpenter Said

THE moon’s a cottage with a door. Some folks can see it plain. Look, you may catch a glint of light, A sparkle through the pane, Showing the place is brighter still Within, though bright without. There, at a cosy open fire Strange babes are grouped about. The children of the wind and tide– The urchins of the sky, Drying their wings from storms and things So they again can fly.

FAMOUSPOETSANDPOEMS

The notes for Plath’s Sheep In Fog show the poet’s increasing fragility as she approached the date she took her own life, aged 30.

Just a fortnight before she died, she returned to a first draft of the poem and rewrote the final lines, in which she describes heaven. Scrubbing out the positive images of “heavenly wools” and “clouds with the faces of babies”, she replaces them with darker references to her dead father.

Poet Laureate Ted Hughes, Plath’s husband, later wrote about the “ominous threat of the last three lines which in hindsight are obviously an anticipation of her death”.

Plath was found dead on February 11 1963 after placing her head in the oven, with the gas turned on. She had sealed the kitchen with wet towels and cloths to stop carbon monoxide leaking out to where her children lay sleeping in the next room.

The first draft of the final stanza of Sheep in Fog, which was completed in December 1962, read: “Patriarchs till now immobile in heavenly wools row off as stones or clouds with the faces of babies”.

But in January 1963, just two weeks before her death, it was dramatically rewritten. “They threaten to let me through to a heaven starless and fatherless, a dark water,” it now said.

The word “fatherless” is thought to be a reference to her own father’s death when she eight years old after he failed to seek help for gangrene in his leg.

Roy Davids, who knew Ted Hughes for more than 20 years and bought the working notes from his and Plath’s son, Nicholas Hughes, said: “The description in her poem of the heaven towards she was being inexorably drawn as ‘fatherless’ strikes right to the very core of Sylvia Plath’s being.

” When she was only eight years old, her father, Dr Otto Plath, a scientist, died, having failed to seek medical help for the gangrene in his leg.

“In her poems, Plath habitually interpreted this not only as him having committed suicide, but also as having deliberately abandoned her.

“The word ‘fatherless’ Sylvia introduced into Sheep in Fog on 28 January 1963 plumbed her depths far deeper than any other she could have chosen.”

He added: “The changes made show signs of her being disturbed.”

Mr Davids is now selling the papers and they are expected to fetch £30-35,000 when they go up for auction with Bonhams on May 8.

TELEGRAPH

Sylvia Plath Ted Hughes interview 1961

|

|

|

Sylvia Plath

Lady Lazarus

I have done it again. One year in every ten I manage it—-

A sort of walking miracle, my skin Bright as a Nazi lampshade, My right foot

A paperweight, My face a featureless, fine Jew linen.

Peel off the napkin 0 my enemy. Do I terrify?—-

The nose, the eye pits, the full set of teeth? The sour breath Will vanish in a day.

Soon, soon the flesh The grave cave ate will be At home on me

And I a smiling woman. I am only thirty. And like the cat I have nine times to die.

This is Number Three. What a trash To annihilate each decade.

What a million filaments. The peanut-crunching crowd Shoves in to see

Them unwrap me hand and foot The big strip tease. Gentlemen, ladies

These are my hands My knees. I may be skin and bone,

Nevertheless, I am the same, identical woman. The first time it happened I was ten. It was an accident.

The second time I meant To last it out and not come back at all. I rocked shut

As a seashell. They had to call and call And pick the worms off me like sticky pearls.

Dying Is an art, like everything else, I do it exceptionally well.

I do it so it feels like hell. I do it so it feels real. I guess you could say I’ve a call.

It’s easy enough to do it in a cell. It’s easy enough to do it and stay put. It’s the theatrical

Comeback in broad day To the same place, the same face, the same brute Amused shout:

‘A miracle!’ That knocks me out. There is a charge

For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge For the hearing of my heart—- It really goes.

And there is a charge, a very large charge For a word or a touch Or a bit of blood

Or a piece of my hair or my clothes. So, so, Herr Doktor. So, Herr Enemy.

I am your opus, I am your valuable, The pure gold baby

That melts to a shriek. I turn and burn. Do not think I underestimate your great concern.

Ash, ash — You poke and stir. Flesh, bone, there is nothing there—-

A cake of soap, A wedding ring, A gold filling.

Herr God, Herr Lucifer Beware Beware.

Out of the ash I rise with my red hair And I eat men like air.

HELLO POETRY

JUST WHISPER HELLO POETRY

FIRST THING ONCE YOU HAVE WAKEN UP, AND LAST THING BEFORE YOU GO TO SLEEP,

JUST WHISPER: HELLO POETRY

AND THEN EVERYTHING WILL BE FINE

MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2017

Klaus Schulze – Heinrich von Kleist

|

|

|

TO THE ENTIRE CATASTROPHE OF BEING A POET

Heinrich von Kleist

A brief survey of the short story part 12: Heinrich von Kleist

He committed suicide at 34, but Heinrich von Kleist was no nihilist. His work, though, is riven with flickering hope and mountainous sorrow

Dan Fredenburgh in Heinrich von Kleist’s play The Prince of Homburg. Photograph: John Haynes/RSC

In one of the last notes he wrote before shooting himself in 1811, Heinrich von Kleist commented that “the world is a strange set-up”. This notion, as terrible as it is mundane, is conveyed repeatedly in the eight tales that represent his slim but influential contribution to the development of the short story.

Writing at the time of ETA Hoffmann, Goethe and Schiller, Kleist seems far less distant from modern sensibilities than those other exemplars of German Romanticism. This is partly a matter of style: his prose is remarkably deadpan, at times reading more like a legal brief than a story, while his typical subject matter marries the traditional folktale with a psychologically astute realism (not unlike the approach adopted by Akutagawa in Japan a century later). It comes as no surprise that Franz Kafka eulogised him as one of the four writers he considered his “true blood-relations”.

Heinrich von Kleist – Kleist on the Road 2012

Kleist was a child of the Enlightenment, but his reading of Kant led him to the conclusion, as the German literature scholars David Luke and Nigel Reeves have it, that “human nature, our own selves, were a riddle, everything that has seemed straightforward became ambiguous and baffling.” In his early 20s he resigned his commission in the Prussian army and abandoned himself, as Robert Walser puts it in his story Kleist in Thun, “to the entire catastrophe of being a poet”. His writings are battlegrounds across which swarm the forces of doubt, paradox and psychological crisis.

For all the sedulous care Kleist takes in presenting his stories as reasoned investigations into unreason (ghosts, possessions and apparent paradoxes recur) he remains constantly aware of the utility of drama, never averse to sudden changes in perspective or a confounding flurry of twists. A narrative such as The Foundling, in which an adopted son’s scheming leads to seduction and murder, sparks with energy. Kleist leads the reader with total assurance into a maze of lust, deceit and evil. Crafting a perfect storm of unlikely but plausible coincidences, he manages to pull off the thriller writer’s trick of making darkness and physical and psychological violence not only compelling, but exciting. What lifts The Foundling beyond being just a masterclass in suspense, however, is Kleist’s determination in pursuing the corrupting effects of such actions to their grotesque ends.

Similarly, The Betrothal in Santo Domingo exerts an extraordinary page-turning force while transcending mere gruesome entertainment, this time playing on racial prejudice. Written shortly after the Haitian Revolution, where the slave population overthrow their French rulers, it uses the love story of a mestiza and a European to subvert the idea of a hierarchy of race-based virtue. It also features another prominently Kleistian trope: that of love being tested by circumstance.

This theme surfaces in several of Kleist’s major works, and casts an interesting light on his repeated assertion that reality is ultimately an unfathomable hall of mirrors. “You should not have mistrusted me” are the heartrending dying words of one character in The Betrothal in Santo Domingo, drawing attention to the fact that Kleist, for all his suicidal urges and fascination with evil, was no nihilist. It is perhaps this fact that gives his stories, so dark in their obsessions and often ending in death or despair, their magnificent impact. Nihilism, one comes to realise, is an easy option when compared with the agony of a repeatedly thwarted humanism.

Such agony is plainly displayed in The Earthquake in Chile, which alongside The Foundling stands as perhaps Kleist’s most striking story. It opens with a young man about to hang himself in prison, and concludes with a mob believing they are doing God’s work by tearing two lovers and a baby to pieces outside the only church in the city left standing by the earthquake. It could not be said to be short on incident, and neither could its brevity be taken as a sign of a lack of ambition, struggling as it does with the most devilish knots in theological, moral and philosophical debate. It also foregrounds the hope Kleist expressed twice in letters in 1806 that, despite the evidence, the world is not in thrall to an evil deity, only a misunderstood one. At its end a survivor looks at the child he will now raise as his own and concludes, “it almost seemed to him that he had reason to feel glad.” In that “almost” there exists both the weakly flickering hope and mountainous sorrow that combines so often in Kleist’s work, and generates its uncanny power.

GUARDIAN

You cannot succeed in one department of life while cheating on another, life is an indivisible whole.

The whole existence of man is a ceaseless duel between the forces of life and death.

Self-sacrifice of one innocent man is a million times more potent than the sacrifice of a million men who die in the act of killing others.

Carefully watch your thoughts, for they become your words. Manage and watch your words, for they will become your actions. Consider and judge your actions, for they have become your habits. Acknowledge and watch your habits, for they shall become your values. Understand and embrace your values, for they become your destiny.

There are two days in the year that we can not do anything, yesterday and tomorrow

Many people, especially ignorant people, want to punish you for speaking the truth, for being correct, for being you. Never apologize for being correct, or for being years ahead of your time. If you’re right and you know it, speak your mind. Speak your mind. Even if you are a minority of one, the truth is still the truth.

Relationships are based on four principles: respect, understanding, acceptance and appreciation.

Our greatest ability as humans is not to change the world; but to change ourselves.

Out of the performance of duties flow rights, and those that knew and performed their duties came naturally by their rights.

The rich cannot accumulate wealth without the co-operation of the poor in society.

(UNFORTUNATELY, USUALLY AT THE EXPENSE OF THE POOR, MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS)

Man is sent into the world to perform his duty even at the cost of his life.

(UNFORTUNATELY OFTEN AT THE COST OF MILLIONS OF OTHER’S LIFE, MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS)

A customer is the most important visitor on our premises. He is not dependent on us. We are dependent on him. He is not an interruption in our work. He is the purpose of it. He is not an outsider in our business. He is part of it. We are not doing him a favor by serving him. He is doing us a favor by giving us an opportunity to do so.

AZQUOTES

Mass civil disobedience was for the attainment of independence.

The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members

(MOST IMPORTANTLY, …IN HOW IT TREATS THE MOST VULNERABLE MEMBERS OF THE MOST VULNERABLE OTHER SOCIETIES, MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS)

The Strange Case of Yukio Mishima – 1985 – BBC – Arena – documentary

|

|

|

Mishima speech (with English Subs)

Confessions of a Mask

The main protagonist is referred to in the story as Kochan. Being raised during Japan’s era of right-wing militarism and Imperialism, he struggles from a very early age to fit into society. Like Mishima, Kochan was born with a less-than-ideal body in terms of physical fitness and robustness, and throughout the first half of the book (which generally details Kochan’s childhood) struggles intensely to fit into Japanese society. Due to his weakness, Kochan is kept away from boys his own age as he is raised, and is thus not exposed to the norm. This is what likely led to his future fascinations and fantasies of death, violence, and sex. In this way of thinking, some have posited that Mishima is similar.

Kochan is homosexual, and in the context of Imperial Japan he struggles to keep it to himself. In the early portion of the novel, Kochan does not yet openly admit that he is attracted to men, but indeed professes that he admires masculinity and strength. Some have argued that this, too, is autobiographical of Mishima, himself having worked hard through a naturally weak body to become a superbly fit body builder and male model.

In the first chapter of the book, Kochan recalls a memory of a picture book from when he was four years old. Even at that young age, Kochan approached a single picture of a heroic-looking European knight on horseback almost as pornography, gazing at it longingly and hiding it away, embarrassed, when others come to see what he is doing. When his nurse tells him that the knight is actually Joan of Arc, Kochan, wanting the knight to be a paragon of manliness, is immediately and forever put off by the picture, annoyed that a woman would dress in man’s clothing.

The word ‘mask’ comes from how Kochan develops his own false personality that he uses to present himself to the world. Early on, as he develops a fascination with his friend Omi’s body during puberty, he believes that everybody around him is also hiding their true feelings from each other, everybody participating in a ‘reluctant masquerade’. As he grows up, he tries to fall in love with a girl named Sonoko, but is continuously tormented by his latent homosexual urges, and is unable to ever truly love her.

WIKIPEDIA

[…]

The effect that Gibson’s debut novel Neuromancer had on me when I read it as an adolescent – comparable to a defibrillator applied directly to my forebrain – was the same effect that it had on speculative fiction in general when it was first published in 1984. People who wouldn’t normally be seen reading a book about a hacker in the future who sneaks on to a space station to help a computer turn into a god – and that’s a lot of people, perhaps including you – they made an exception for Neuromancer, because it was just too brilliant to ignore. Neuromancer originated a subgenre of science fiction called cyberpunk, which later withered away, redundant, because cyberpunk had become the condition of the real world. Gibson could therefore be credited with anticipating the information age, with the result that for the last 30 years he has regularly been pressed into service as a prophet. And yet you’re not giving his fiction its due if you just score it on the accuracy of its predictions like a six-horse accumulator. Call me biased, but I think the most interesting thing about a novelist is the inherent quality of his or her novels. And Gibson’s – 11 so far – are some of the best and most singular novels by anyone writing in English.

[…]

We visited because this was the setting of one of the climactic scenes of Gibson’s 2007 novel Spook Country, in which “the narrow park leap[s] into shivering, seemingly shadowless incandescence” as a spy flees a patrolling helicopter.

Spook Country is not the book that Gibson, 66, is currently promoting. That is his superb new novel The Peripheral. But The Peripheral is set partly in the American south in the 2030s, and partly in London in the 2100s, so it would have been difficult to find a directly relevant excursion within the Vancouver city limits.

In the book, it’s a sort of transtemporal Skype running on a mysterious Chinese server that accounts for those two eras becoming entangled in a single story. By bringing them face to face, Gibson was addressing the tendency of any given generation to assume that “the inhabitants of the past are hicks and rubes, and the inhabitants of the future are effete, overcomplicated beings with big brains and weak figures. We always think of ourselves as the cream of creation.” Although he generally defers to his unconscious when asked about his creative process, Gibson allowed that this book may have had its origin in a news story he read about a midwestern Christian militia called Hutaree whose members were arrested in 2010 for an alleged conspiracy to kill local police officers.

[…]

“The thing that struck me was that several very young teenagers had been left to fend for themselves when all of the adults had been taken away to jail,” he said. “I started imagining being one of those kids and how I would understand the world.” The setting also fed on Gibson’s own upbringing in small-town South Carolina, the film Winter’s Bone and the HBO series Deadwood, about a lawless town during the Gold Rush. “I wanted the equivalent of the city slickers, from a very different world, turning up in Deadwood. Initially I thought the other world would be New York or Los Angeles. But at some point I realised that could be the future.”

[…]

The amazing thing is, Gibson is cool in the other sense, too. Imagine a science-fiction novelist in his mid-50s, with grown-up children, living in a suburban house in Vancouver, sitting down and saying to himself: “I am going to create a female character 20 years younger than me, and she’s going to be one of the coolest characters in modern fiction, so cool that a decade later people on fashion message boards will still be discussing the personal style of this imaginary person, so cool that a Japanese company, Buzz Rickson’s, will do a brisk trade in £400 replicas of her bomber jacket.” (That monologue is a dramatic reconstruction, not a direct quote.) In almost any other hands, it would have been laughable and embarrassing, but Gibson came up with Cayce Pollard, the formidable protagonist of his 2003 masterpiece Pattern Recognition (who works as a professional “cool hunter”).

Of course, when Sonic Youth have already written songs based on your novels [“The Sprawl” on Daydream Nation], it must give you a bit of confidence in that respect. Also, he told me: “I came originally from a place that had a serious cool deficit, so I really became a nerdish tabulator of cool. As a writer, I wanted to know how it worked because I judged it to be one of the only engines of global commerce that I had any talent for deconstructing.” Today, Gibson is one of those rare figures, like Patti Smith or David Lynch who, as they enter their late 60s, do not resign from cool but rather merge with it and become part of its specifications. You wouldn’t immediately know it to look at him: although he knows more about men’s clothes than any other novelist I’ve ever met, he seems to feel that at his stage of life it would be unbecoming to draw too much attention to his appearance. So no Lynchian pompadour.

[…]

He once wrote that the enigma of London “has troubled me quietly and constantly, and I have returned there more repeatedly, and more determinedly, than to any other world city”. The Peripheral is the fourth of his novels to be set at least partly in the capital, and by far the most trenchant in that respect. In the early 22nd century, London is eerily deserted, and most of the characters we meet are either Russian oligarchs or working for oligarchs.

“One of London’s roles today seems to be to be the natural home of a sometimes slightly dodgy flight capital,” Gibson observed. “It’s where you go if you successfully rip off your Third World nation. And there’s a huge industry of people there who are just there to facilitate that move, if you’ve got the readies. I can’t help but think that that will eventually come back to bite somebody’s ass, although it may well be your grandchildren’s.” Gibson told me that when he visits London, he’s struck by the extent to which overseas money has warped the fabric of the city, but even more so by “the denial of my lifelong Londoner friends. Some people just don’t seem to see that there’s anything happening to it, even though it seems to me to be such a radical change. It amazes me when people argue: ‘Oh, it’s only happening in that neighbourhood, and if that’s no longer fun we’ll just move.’ I thought that was what the developers wanted you to do so you can gentrify the next bit.”

A further quality of The Peripheral’s future London which cannot have represented a crippling expenditure of imaginative resources is that the city finds itself captive to an unchecked financial establishment. “I was talking with Nick Harkaway in his back garden a couple of years ago and he started explaining how the guilds of the City work.” In particular, Harkaway told him about the unelected offices of the Lord Mayor and the City Remembrancer, who can be mistaken for figureheads but, in fact, have extensive powers. “To this day I still don’t know if he was pulling my leg, totally making it up, or giving me a very accurate description of it.” (“Well, basically it’s true,” Harkaway clarified by email. “I’d just come off a weird and wonderful trip that the City of London PR office organises every year for writers.” If they ever read The Peripheral to the end, that office may have second thoughts about the image benefits of getting novelists interested in this kind of thing.)

Then there’s the other half of the book. Gibson described The Peripheral to me as “a sort of two-headed dystopia in which it’s impossible to decide who’s got the worst deal”. Just like the London of the 2100s, the rural American south of the 2030s is thrown off balance by the recently landed – but here it isn’t foreign oligarchs, it’s veterans returning from yet another American war, scorched and futureless, with nothing much to do but play around with surveillance drones and attack drones that are as plentiful as chickens.

It has been a constant of Gibson’s work that we live in a sort of military surplus society, where military technologies and philosophies are forever leaking into civilian life. When he watched the coverage of the Michael Brown protests in Ferguson, Missouri, where police in full camouflage drove armoured vehicles through the streets of a small town, it felt almost like an adaptation of his own work. “Ferguson,” he told me, “is very much the implicit rural America of Virtual Light,” his fifth novel, which was published in 1993 and set in around 2006. “I haven’t found anybody who’s been able to convince me that it’s necessary to arm those small-town police forces with Iraq-grade equipment. So it’s got to be good for somebody. It’s definitely good for the contractors who are paid handsomely to build those vehicles. There are chains of intergovernmental commerce there that I know nothing about, but given human nature I’m a bit suspicious of.”

Gibson does not, in fact, “know nothing about” such contractors, because they were among the villains of Zero History. Regardless, he was able to counterpose a more benign but equally plausible (and Gibsonian) conspiracy theory about American police forces buying armoured vehicles from the army. “I’ve heard that in some small towns in the United States, buying that sort of equipment was a very effective way to address the potential dangers of militia movements,” such as the aforementioned Hutaree. “Those movements can be trouble – they can turn to crime. But if you start an official county militia and you get a tank, they’ll come and join your militia, and then you start training them. ”

[…]

And yet not all of The Peripheral is the present dressed up as the future. Some of it is the future wearing no disguise. Explaining the reasons for London’s sepulchral quiet, Netherton tells Flynne that a lot of apocalyptic dominoes fell, but it began, of course, with the climate: “People in the past, clueless as to how that worked, had fucked it all up, then not been able to get it together to do anything about it, even after they knew, and now it was too late.” This is not futurology as satire, any more than a long-range weather forecast is satire. James Lovelock, after all, has predicted that 80% of humans will perish by AD2100, and the same figure can be found in the novel. If Gibson gives us catastrophe, it’s because right now he finds catastrophe plausible. “Since I turned in the book, every time I open my news feed I see something and wince and think: ‘I didn’t even factor that in.’ It doesn’t look good. I’m reluctant to say it, because people my age have always said we’re going to hell in a handbasket. I’ve heard it all my life from some writers who were then the age I am now. So I think: ‘Am I due yet? Have I started to do that?’ But it really doesn’t look good…”

[…] and third, the details of our fate are mostly confined to that one scene towards the end, when Netherton, our descendant, explains what happened before he was born. As we read it, we ought to be like Flynne, who sits under the oak in her front yard and listens without hysterics as she hears the story of a world in which “everything, however deeply fucked in general, was lit increasingly by the new.”

GUARDIAN

A Man of Many Masks – Kobo Abe

Kōbō Abe (安部 公房 Abe Kōbō), pseudonym of Kimifusa Abe, was born on March the 7th 1924 in Kita, Tokyo, he grew up in Mukden (now Shen-yang) in Manchuria during the second world war. In 1948 he received a medical degree from the Tokyo Imperial University, yet never practised medicine. As well as a writer, he was also a poet (Mumei shishu “Poems of an unknown poet” – 1947) playwright, photographer and inventor. Although his first novel Owarishi michi no shirube ni (“The Road Sign at the End of the Street”) was published in 1948 which helped to establish his reputation, it wasn’t until the publication of The Woman in the Dunes in 1962 that he won widespread international acclaim.

Often described as an Avant- garde playwright & novelist, sharing the same literary map as the likes of Samuel Beckett, Franz Kafka and Eugene Ionesco through a shared sense of the absurd & the central theme of an alienated and isolated individual at loss in a world. Kobo Abe manages to do this within the realms of genres that would be recognised by most, fancy a detective novel The Ruined Map, Science Fiction, Inter Ice Age 4, Fantasy Kangaroo Notebook, there’s even a love story aspect to The Face of Another.

In the 1960’s he worked with the Japanese director Hiroshi Teshigahara on the film adaptations of The Face of Another, plus The Pitfall, Woman in the Dunes and The Ruined Map. In the early 1970’s he set up an acting studio in Tokyo, where he trained performers and directed plays. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1977. Among the honours bestowed on him were the Akutagawa Prize in 1951 for The Crime of S. Karuma, the Yomiuri Prize in 1962 for Woman in the Dunes, and the Tanizaki Prize in 1967 for the play Friends. Kenzaburō Ōe stated that Abe deserved the Nobel Prize in Literature, which he himself had won (Abe was nominated multiple times).

Kobo Abe through his work as an Avant-garde novelist & playwright, has had names of the calibre of Albert Camus, Alberto Moravia, & Franz Kafka, (as well as those mentioned above) thrown at him and, like Kafka, there is an apparent clinical detachment in the writing, as though Abe’s medical background has had a direct influence upon his writing style, and yet with this there is also an elegance that makes his novels an immensely enjoyable and also an incredibly satisfying read – on all levels.

A brief glimpse at his English Language Works.

Inter Ice Age 4 (1959) Plot elements include submersion of the world caused by melting polar ice, genetic creation of gilled children for the coming underwater age, and a fortune-telling computer predicting the future and advising humans how to deal with it. A number of critics have identified Inter Ice Age 4 as Japan’s first full-length science fiction novel, and a work that helped jump start Japanese interest in the genre.

*************************************************************

The Woman in the Dunes(1962) An amateur entomologist searches the scorching desert for beetles. As night falls he is forced to seek shelter in an eerie village, half-buried by huge sand dunes. He awakes to the terrifying realisation that the villagers have imprisoned him with a young woman at the bottom of a vast sand pit. Tricked into slavery and threatened with starvation if he does not work, his only chance is to shovel the ever-encroaching sand.

********************************************************

The Face of Another(1964) A plastics scientist loses his face in an accident and proceeds to obtain a new face for himself. With a new ‘mask’, the protagonist sees the world in a new way and even goes so far as to have a clandestine affair with his estranged wife. There is also a subplot following a hibakusha woman who has suffered burns to the right side of her face. In the novel, the protagonist sees this character in a film (click link for my post).

***********************************************

The Ruined Map(1967)The story of an unnamed detective, hired by a beautiful, alcoholic woman, to find clues related to the disappearance of her husband. In the process, the detective is given a map (a ruined one), to help him, this turns out to be more like a metaphor of the guidelines one should have in life. The impossibility to find any relevant clues to solve the mystery leads the main character to an existential crisis, building slowly from inside, this finally puts him in the position of identifying himself with the man he was supposed to find.

The Box Man(1973) A nameless protagonist gives up his identity and the trappings of a normal life to live in a large cardboard box he wears over his head. Wandering the streets of Tokyo and scribbling madly on the interior walls of his box, he describes the world outside as he sees, or perhaps imagines it, a tenuous reality that seems to include a mysterious rifleman determined to shoot him, a seductive young nurse, and a doctor who wants to become a box man himself.

********************************************

The Secret Rendezvous (1977) From the moment that an ambulance appears in the middle of the night to take his wife, who protests that she is perfectly healthy, her bewildered husband realizes that things are not as they should be. His covert explorations reveal that the enormous hospital she was taken to is home to a network of constant surveillance and outlandish sex experiments. Within a few days, though no closer to finding his wife, the unnamed narrator finds himself appointed the hospital’s chief of security, reporting to a man who thinks he’s a horse.

**************************************************

The Ark Sakura(1984)The Protagonist, Mole has converted a huge underground quarry into an “ark” capable of surviving the coming nuclear holocaust and is now in search of his crew. He falls victim, however, to the wiles of a con man-cum-insect dealer. In the surreal drama that ensues, the ark is invaded by a gang of youths and a sinister group of elderly people called the Broom Brigade.

****************************************

*************

The Kangaroo Notebook(1991). The narrator of Kangaroo Notebook wakes one morning to discover that his legs are growing radish sprouts, an ailment that repulses his doctor but provides the patient with the unusual ability to snack on himself. In short order, Kobo Abe’s unravelling protagonist finds himself hurtling in a hospital bed to the very shores of hell.

****************************************

Beyond The Curve(1993) This Collection of tightly drawn, surrealistic tales proceed from the same premise: an ordinary individual is suddenly thrust into extraordinary, often nightmarish circumstances that lead him to question his identity, this is an entertaining and fascinating volume. Some stories have the feel of sketches that might be further developed in Abe’s longer fiction, and the influence on a new generation of writers, such as Haruki Murakami, can be readily seen.

Kobo Abe, manages to astound and amaze & yet remain within the realms of what could be defined as the mundane reality of the world about us. His protagonists start in what to all intents & purpose could be our daily world, before turning round and realising they are as far removed from the “normal” as they are from the distant stars. What is truly fantastic though is that we follow him, not just with our belief suspended, but with a growing awareness that although grotesque, absurd and surreal, we still recognise it as our world.

PARRISHLANTERN

|

|

|

GOOGLE: https://hellenicpoetry.com

Gogou, Katerina: Athens’ anarchist poetess, 1940-1993

A biography of Katerina Gogou the anarchist poetess of Exarcheia.

This is a biography of greece’s greatest anarchist poetess, Katerina Gogou (1940-1993). Until today Gogou remains the bete-noire of modern poetry in Greece with only one poetic anthology including her groundbreaking heretical work. However, her poems have become an indivisible part of the radical culture of the country and of the public imaginary of Exarcheia. Recently a biography of Katerina Gogou titled “Katerina Gogou: Death’s Love [Erotas Thanatou]” appeared, authored by Agapi Virginia Spyratou (2007, Vivliopelagos, Athens), based on her doctoral thesis. However no study or history of Katerina Gogou’s involvement in the anarchist struggle of the 1980s has ever been published in greek, leaving a great gap in both the history of the movement and in the biography of the poetess. The biography presented below is based on the book of Sryratou as well as on several reviews of her life and work in literary magazines like Odos Panos (Vol. 145, July-September 2009). The only translation of her work in English is an old publication of her first collection of poems “Three Clicks Left”, translated by Jack Hirchmann and published in San Franscisco by Night Horn Books. The book not being available in greece, I have provided my own translations to her poems with asterisks for explanations on notions and places (apologies for my literary sloppiness in advance). The original format of the poems is generally preserved, but no titles are given as her poems had no titles. Links to videos of Gogou reciting them are given where available. The recitations heard are from the vinyl record “On the Street” described below. Weird screeching siren like noises interrupting the recitation at places is no digital mistake but the 1980s not-so-subtle censorship of “inappropriate words” and political comments by the authorities.

Katerina Gogou was born in Athens on the first of June 1940 and spent the first years of her childhood in the harshest conditions of the Nazi occupation when famine due to conscription of all edibles led to hundreds of thousands of deaths in Athens. Her memories of the years of the Nazi occupation, the Resistance and the Civil War are reflected in a piece of prose published post-mortem from her unfinished poetical authobiography “My name is the Odyssey”:

“Gang-war 1 Aaaaaaaaa! This is the gang-war. Grrrrreeks with big hats, I know, they called them republicas. Square, biiiig, with long coats and cabardines, they had guns in their pockets, maybe more gun inside. With their hands in their pockets they shot other Greeks and they walked fast as if in a great hurry or as if someone was chasing them. I wanted -they did not let me, they said- to go out. Out I wanted. There I wanted. To the “It Is Forbidden”. In our corner, Lambrou Katsoni and Boukouvalla, piles of eaten cats and famine corpses -they called them trash- parents and children. I saw through the glass a bullet hitting my left hand palm, blood and the trash breathing. My mother was in the kitchen and my father I don’t even know where, I open the door and I go to the trash. And there I saw, and I don’t give a dime if you don’t believe me, the most beautiful boy I had seen in my life. He was covered there, holding a machine gun, he had a short blond beard and long blond hair. His eyes…I don’t know to tell their colour. He looked like or was the Christ. “Go little girl, go”, he told me, “away from here. They will kill me”. I took a deep breath to run fast. “Bend so I can kiss you”, he told me. I was already home. The first man and the last I ever loved was an urban guerrilla”

Her teenage years were spent in down-town Athens of the post-Civil War monarchy, an era of strict censorship, police terror, and exile island camps filled with political prisoners. In “My name is the Odyssey” Gogou recalls one of the rare moments when she could express her indignation to the order of things alongside hundreds of other teenagers when the movie “The Blackboad Jungle” (1955) was screened in Pallas, Athens’s most prestigious cinema: “When the movie came to town, the movement of all the angry children from even the farthest neighbourhoods and from down-town Athens gathered […] when the song of the movie was heard, the famous “One two three o’ clock four o’clock rock”, half of the crowd light their lighters and the other half tore the velvet armchair of the so-aristocratic Pallas with razors. I did both”. It was the birth of the Teddy Boy tendency in Athens, which was soon to be ruthlessly repressed by the Law No.4000, which prescribed forced public humiliation by means of scalp shaving of “teddy-boys”.

A few years later Katerina Gogou, already working in theatre, graduated from high school and enrolled in a series of drama and dance schools of Athens. Within the strict censorship of the post-civil war monarchy, the only place she could make a living as an actress was the greek comedy industry, a major factor in social reproduction of statist, capitalist and patriarchal values at the time. The roles ascribed to Katerina by Finos Films, her employee company, were usually the secondary role of the naive domestic servant, or of the silly little sister, or of the undisciplined school pupil. Her most characteristic role was the one played in the “Beating came from Paradise” in 1959 where next to the regime’s favourite actress, Aliki Vouyouklaki, she played the incumbent rascal pupil that made her famous. Until the collapse of the colonels’ junta in 1974 she played in dozens of other block-buster comedies, always in the same range of roles. As Spyratou puts it, “the world of the cinema composed the capitalist ideal as a consumer society, where the positive heroes supported order within the limits of the traditional family and within the patriarchal state”. Despite performing a never ending series of female stereotypes, Katerina Gogou developed an acute radical perspective far removed from the nominal conservative feminists of the post-junta era who she mocked bitterly in an 1980 poem from the collection “Idionimo”:

“They shoot to kill. – They are shooting in the air, they 2 cried Then the small hole in front of the bus stop was filled with blood – They are only plastic bullets, they said Then he fell – He has fainted, they cried. Then he was motionless, But they were already on their way. He was still, But they had already taken the trolley-bus, and gone. Gone were they”

Katerina Gogou’s feminism was far removed from the official republican exercises in democratic progressiveness. Many of her early poems talked about a world greek society, including the late 1970s ideologically dominant left, ignored or wanted to ignore: prostitution. A large part of Katerina’s poetry was dedicated to a viral description of the dark side of Athens, in a way no one had dared articulate that far:

“Oily food in a plastic bawl in Acominatou street outside the door, August white like sheets the whores 40 degrees in shadow 4 o’clock p.m. The legs open by themselves Like dead oysters The street is filled with coloured underwear Pakistanis 3, anti-mosquito chemicals, limping women, snitches And faggots injecting their breasts Filled with carcinomas. The street is filled With destroyed fallopian tubes and discarded uteri The belly is swollen By useless sperm – no child is conceived here nothing is caught out of nothing Magdalene and Vanou did the job The money lenders and the saint of the neighbourhood are foul First they get bribed and then they snitch on you That’s the way it is You have spread whores all across Metaxourgeio 4 Under the scorching sun with not a tree around – for shadow Not even a stone wall – to lie against. Enraged citizens 5 and religious groups have made a pact. They got organised. They brought bottles And petrol. They will soak you. They will burn you, they say. Like rats, they say. Armoured vans filled with policemen Impotent voyeurs, the doctors of the Vice Department Crabs are taking a stroll all day on your brain The whistle boys are the syphilis of your sleep – whose side are they on. Here we burn the witches. We fuck the whores. A poster of Karamanlis Your eyes a picture Threads of handiwork Bold wig, bruised nipples And evictions are closing in around your hair and throat They tie you hands and feet on the bed You and us as well The way and the tariff changes The place and the name changes In Larissa 40 degrees Here at the cross, the sun” (from the collection Wooden Coat, 1982)

For Gogou, Spyratou writes, “prostitutes were not a social fact, they were a social formation and as such they were a necessary part of the reproduction of control: a woman must be a whore when the man demands it, and must prove she is not a whore in order to be a wife and a mother. In both cases it is the male imagery of femininity that must be satisfied”. As for her ideal woman figure, she was a revolutionary nonetheless, but a revolutionary unfit for the leftist heroicism of the republican era [Metapolitefsi]:

“She is dangerous – when god is bringing down the world with hail and rain she comes out on the streets without socks and whistles at the men she throws stones at the police cars and lies like a squirrel on trees lighting her cigarette with thunders. The last time she was spotted at the same date and year in three different places – based on valid information the blown up bridge of Manhattan the delivery of weapons to anarchocommunist movements as well as the exportation of top secret state information are to be attributed to the same person. She is believed to be wearing a red or black military woolly jumper childish pearl ribbons in her hair with her hands in the pockets of a borrowed jacket. Place of birth: unknown Sex: unknown Vocation: unknown Religion: atheist Eye colour: unknown Name: Sofia Viky Maria Olia Niki Anna Effie Argyro Darius Darius. To all patrol cars Attention she is armed. Dangerous. Armed. Dangerous Her name is Sofia Viky Maria Olia Niki Anna Effie Argyro And she is Beautiful Beautiful Beautiful Beautiful my god…” (From the collection Idionimo, 1980)

LIBCOM

The first collection of poems published by Gogou in 1978 “Three Clicks Left” is a vitriolic depiction of an Athens not proper to the leftist heroics and the republican thriumphism of the time. Gogou identified with the damned of the metropolis, with the lumpen fringe like no other writer or thinker had done before, causing an immediate adoption of the poetess by the newly born anarchist milieu of Exarcheia and beyond, a relation that developed into a mutual bond of trust and respect until the poetess’ death. The end of the 1970s was a time when the initial post-junta revolutionary chic was giving way to more substantial and contradictory urban cultures and movement, with many workers breaking free from the unions and the left, mass factory occupations, the first occupations of universities and a ferocious armed struggle against unpunished agents of the junta, with the far-right responding with bombs in cinemas, squares and leftist offices. It was this era with the increasing disillusionment of Athens radical youth with the classic leftist currents and the first experimental steps towards anarchism that the forgotten lumpen fringe of prostitutes, junkies, psychiatric patients, prisoners etc acquired a political importance of the “unrepresented” that would provide the moral basis of the 1980s anarchist movement. Gogou was a true prophet of this unexpected political and social development, and her poems got to be respected exactly for that:

“Our life is pen knives in dirty blind alleys rotten teeth faded out slogans bass clothes cabinet smell of piss antiseptics and moulded sperm. Torn down posters. Up and down. Up and down Patission 6 Our life is Patission. Washing powder which does not pollute the sea And Mitropanos 7 have entered our lives Dexameni 8 has taken him from us too Like those high ass ladies. But we are still there. All our lives hungry we travel The same course. Ridicule-loneliness-despair. And backwards. OK. We don’t cry. We grew up. Only when it rains We suck secretly on our thumb. And we smoke. Our life is Pointless panting In set-up strikes Snitches and patrol cars. That’s why I tell you. The next time they shoot us Don’t run away. Count our strength. Lets not sell our skin so cheeply, damn it! Don’t. Its raining. Give me a fag”

At the final years of the 1970s Gogou re-engaged in cinema, this time however in radically different roles than the female stereotypes of her earlier career. Her new début was made in the ground-breaking film “The Heavy Melon” (1977), the first attempt of a greek social neo-realism, directed by her husband and father of her only daughter, Pavlos Tassios. The film describes the new urban working class composed of déclassé village petty owners. Gogou appears as a “by the piece” industrial worker who breaks the appointed work time limit for a minimal profit, and seeks refuge in love only to finds that it simply entraps her in more work of a domestic-patriarchal nature. For her role Gogou was awarded the best female actress award in the Salonica Film Festival. A few years later, in 1980, she will again perform in the big screen for “The Order” [Paragelia], again directed by Tassios. The film sought to depict the life of Nikos Koemtzis: on February 1973 after being released from prison, Koemtzis went to the music night club Neraida with friends, where his brother ordered from the orchestra to play a zeibekiko called “Vergoules” by the rebetis Marcos Vamvakaris. When other men stood up to dance as well [zeibekiko is a solo male dance from Asia Minor], the singer announced they should sit down as the song was “an order”, a fight ensued and Koemtzis stabbed to death three policemen thinking they were killing his brother. Koemtzis case became a celebrated issue in mid and late 1970s greece, representing a figure-out-of-time, a man obsessed with his honour in a society that was moving to an altogether different ethical code. The film featured a series of recitations of poem from “Three Clicks Left” by Gogou under the vanguard musical score of Kyriakos Sfetsas, the future director of the “Third Programme”, greece’s prestigious classical music state radio. The recital and musical score won the best music award in the Salonica Film Festival and was soon published in vinyl to become one of the musical fetishes of radical culture in the 1980s. It remains today one of the boldest attempts of combining poetry with music in greece. The best known poem recited during the film has direct political implications for the state of things in republican Greece.

“Loneliness does not have the saddened colour of the cloudy bimbo in her eyes. She does not stroll abstractly and self-content Shaking her hips in concert halls And in frozen museums. She is not the yellow cadres of “good” old times And naphthalene in granny’s chests Rosy ribbons and straw hats. She does not open her legs with fake small laughers A cow’s gaze rhythmic sighs And assorted underwear. Loneliness Has the colour of Pakistanis, this loneliness And she is counted inch by inch Along with their pieces In the bottom of the light-shaft. She stands patiently queuing Bournazi – Santa Barbara – Kokkinia Touba –Stavroupoli – Kalamaria 9 Under all weathers With a sweaty head. She ejaculates screaming and smashes the front windows with chains She occupies the means of production She blows up private property She is a Sunday visit in prison Same step in the yard revolutionaries and penal prisoners She is sold and bought minute by minute, breath by breath In the slave markets of the earth – Kotzia 10 is near here Wake up early. Wake up to see it. She is a whore in the rotten-houses The german drill for conscripts And the last Endless miles of the national highway towards the centre In the suspended meats from Bulgaria. And when her blood clots and she can take no more Of her kind being sold so cheaply She dances barefoot on the tables a zeibekiko Holding in her bruised blue hands A well sharpened axe. Loneliness, Our loneliness I say. Its our loneliness I am speaking about, Is a axe in our hands That over your heads is revolving revolving revolving revolving”

The same year, 1980, Gogou published her second poetic collection, “Idionimo”. The title of the collection referred to Law No.410/1976 which fortified the security forces against protesters and the regime itself against strikes etc. The law was dubbed “idionimo” by anarchists and leftists at the time, a word referring to the law passed in the late 1920s by the liberal PM Eleftherios Venizelos which ordered the expulsion of communists to barren island camps. In the poetical collection Gogou attacked the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) for treason of the struggle. The accusations came as the youth of the Party, KNE, had formed a special force, the Communist Youth for the Restoration of Order (KNAT rhyming with MAT, the riot police) used to brutally repressed any attempt of autonomy and anti-police violence during the first university occupation of 1979-1980. Anarchist magazines like “The rooster crows at dawn” at the time indicated that KNE actually tortured anarchists in special rooms of the Polytechnic. The 1979-1980 university occupations against the educational law No.815 was a sort of a greek May ’68, with the youth for the first time massively mocking communist and leftist orthodoxy, especially KNE and EKKE, the numerous Maoist Party that had already clashed with anarchists in 1977 in Exarcheia.

By 1980 Gogou was deeply involved in the sprouting anarchist culture of Exarcheia where the first Athens squat appeared on Valtetsiou street in 1981. Two years earlier, in 1979, Gogou played a central role in the big concert against police repression in Sporting, where many singers at the time took part. The concert was in demand for the immediate release of Philipos and Sofia Kiritsi, two anarchists imprisoned as terrorists by the regime. The Kiritsis affair was the first emblematic anarchist repression case, and played an important role in the creation of the milieu via the solidarity movement that arose for the liberation of the comrades. Naturally, the concert ended in riots with over 100 people arrested. It was the era of the great concert-riots which reached its climax during the spring 1980 concert of the “Police” in Sporting. It was the first rock concert in greece after the Rolling Stones concert during the junta had ended with the police entering the stage and beating the band manager after Mick Jagger threw carnations to the audience, an act deemed to be a conspiratory communist signal by the cops. During that warm night of March 1980, while all universities were occupied, 2,000 young people stormed the stadium with no tickets leading to extended clashes with the police across Patision and Aharnon avenues.

In 1982 Gogou publishes her third poem collection “Wooden overcoat” where her poetry acquired a personal touch, while in 1984 Gogou played in her last role for the film “Ostria –endgame” whose scenario she wrote herself. The film, again directed by Tassios, narrates the story of three couples who sold out their revolutionary ideas for petty-bourgeois comfort, a theme castigating the entire “generation of the Polytechnic” by then well entrenched in positions of power and exploitation.

In 1986, Gogou publishes her fourth poem collection “The Absentees” well known for the poem dedicated to the murdered anarchist transvestite Sonia:

“She bent her pale head with a sigh and fell asleep for ever Above her the sky mountainous Barren landscape –dark- stones only and rocks not even rain… Bride you with the plastered mouth red Brocade hands melted handiwork Offered pleadingly Some lilies Around the fresh earth your girlfriends Sad and over-painted Making strange noises As craving attention In order to play in some film Here this ring child poem Word of Honour This hour that the future-ones Learn the eagle’s flight This hour that your forehead Reveals what is hidden Always the same hour That the RED KNIVES Kill the Different ones…”

The red knives in the poem referred to the traditional communist policy against homosexuality deemed by the KKE “a bourgeois perversion that will disappear with the revolution”. The mid 1980s was a time of fierce gay liberation struggle in greece. Only a few years before, in 1979, the right wing government had proposed a law for the displacement of homosexuals to barren island camps. The law was overturned only by way of mass grassroots reaction as well as international pressure from intellectuals like Foucault and Guattari. The struggle against the displacement law was the cradle of the gay liberation movement of the 1980s mostly led the leftist group AKOA. The most militant part of the struggle however was played by transvestites (this was their self-referential term) who even clashed with riot police forces. Sonia was an anarchist transvestite closely related to Paola, the leading anarchist trans figure of the decade who published Kraximo [Heckling] a transvestite anarchist magazine that led her to numerous arrests. Sonia’s assassination and the abandonment of her brutalised naked corpse on desolate rocks on the Attiki coastline was a emblematic call to arms affair at the time.

Gogou herself was a consistent victim of police violence and arbitrariness. In 1986 she pressed charges against General Drosoyannis, the notorious Minister of Public Order of PASOK, after being brutally beaten by riot policemen during one of the numerous anarchist marches of the time. Gogou was on the Ministry’s constant suspect list, a fact only worsened by her friendship and comradeship with Katerina Iatropoulou, the leading prison abolition anarchist figure of the time. Gogou’s struggle against repression is best depicted in her poem “Some times”-the poet can been seen in this sequence from ‘The Order’ at the initial frames:

“Some times the door opens slowly and you enter. You wear an all-white suite and linen shoes. You bend, you tenderly put 72 coins in my palm and you leave. I have stayed in the same position where you left me, so that you can find me again. But a long time must have passed because my nails Have grown long and my friends are scared of me. Every day I cook potatoes. I have lost my imagination. And when I hear ‘Katerina’ I am scared I think I have to denounce someone. I have kept some newspaper clippings about a man they claimed was you. I know the papers lie, because they say they shot you at the feet. I know they never aim at the feet. The mind is their target. Hold it together, eh?”

In 1988, Katerina published her fifth book titled “The Month of Frozen Grapes”, a collection of 38 poems many of them consisting of a couple of verses, or even a single line. The collection reflected a time of ravaging psychological anguish that led Gogou in and out of clinics for the rest of her life. A characteristic poem (no.17) reads:

“I was a tree and I broke They broke all my branches Because there found refuge all the lost children So as to play the hanged.”

Finally in 1990, Katerina published her last book “The Return Journey” which combined both her earlier political and social penetrating gaze and her existential angst. In one page of the book a hand-drawn box contains five names that marked the birth of the anarchist movement in greece, five men who died by police bullets, the urban guerrillas Kasimis, Tsoutsouvis and Prekas, the 15 year old boy Kaltezas shot by a cop in 1985 during the Polytechnic anniversary march, and Tsironis, the eccentric revolutionary doctor who had proclaimed his appartment a free state and shot down by special forces. The prose-poem above the drawing reads:

“The terror of the silent danger of the freezing silence that climbs the steps with proplasmatic faces, who slowly move in line. The hunted down knows. He has great pains behind the ears and deep in the stomach. The features change, he becomes younger, more handsome, he enters the final clash, he climbs gloriously to his god. All the more as the cause for his persecution included the justice of ever more people. He is no more in pain. Now terror sits on the shoulders of his hunters. Now they will take aim. Now they will murder. They murder. Their human face took its form in conscious retreat. They will devour each other in eternal fire to eternity. The angels get ever more numerous”.

Katerina Gogou died on October 3 1993 at the age of 53 due to an overdose of pills and alcohol, the last among the triad of radical poet-singers (alongside Pavlos Sidiropoulos and Nikolas Asimos) to exit the changing stage of Exarcheia. Her funeral gathered thousands of people. A lost poem of Katerina unearthed and published in her recent biography reveals her unwavering commitment to anarchy:

“Don’t you stop me. I am dreaming. We lived centuries of injustice bent over. Centuries of loneliness. Now don’t. Don’t you stop me. Now and here, for ever and everywhere. I am dreaming freedom. Though everyone’s All-beautiful uniqueness To reinstitute The harmony of the universe. Lets play. Knowledge is joy. Its not school conscription. I dream because I love. Great dreams in the sky. Workers with their own factories Contributing to world chocolate making. I dream because I KNOW and I CAN. Banks give birth to “robbers”. Prisons to “terrorists”. Loneliness to “misfits”. Products to “need” Borders to armies. All caused by property. Violence gives birth to violence. Don’t now. Don’t you stop me. The time has come to reinstitute the morally just as the ultimate praxis. To make life into a poem. And life into praxis. It is a dream that I can I can I can I love you And you do not stop me nor am I dreaming. I live. I reach my hands To love to solidarity To Freedom. As many times as it takes all over again. I defend ANARCHY.

1. Gang-war [Symmoritopolemos] was the official monarchist term for the Civil War, current until the mid 1970s.

2. “They” [Autes] in feminine plural (Elles – fr) indicates the Movement of Democratic Women [Kinisi Dimokratikon Gynaikon], the most numerous women’s organisation at the time which after 1981 was recuperated into the Socialist State apparatus to provide the cadres of the Secretariat of Equality. The poem was written in 1980, the year when during the Polytechnic Uprising anniversary march, one worker and one student, Koumis and Kanellopoulou, were killed by the riot police forces (MAT) – the official stance of the socialist opposition was a complete cover-up of the incident.

3. Pakistanis where the first immigrant worker population in Athens well before the first wave of immigration in the 1990s. Pakistani workers in the mid 1970s organised one of the fiercest wildcat strikes, at a time where the movement for proletarian autonomy was at its high noon.

4. “Metaxourgeio”, the down-town Athens area south of Omonoia square, a devalued working class neighbourhood which slowly became a derelict district of collapsing houses, car garages and the main red-light zone of Athens. Despite some efforts to gentrification the area remains the same today.

5. “Enraged citizens” [aganaktismenoi polites] is a terms used until today by the media as a euphemism for fascist groups and para-state thugs.

6. Patission is the avenue joining Ano Patissia with Omonoia square passing next to the Polytechnic and the ASSOE university as well as to Athens’ major squares (Victoria, Amerikis, Kolliatsou) in between Patissia and Kypseli, the most densely populated areas of the metropolis. It is considered to be the “radical avenue” of the capital, the first to be affected by civil disturbances.

7. Mitropanos is a popular singer of working class origin identified with chain-smoking male proletarian culture, he was recuperated first in the post-junta left-wing republican music scene, and then in the music entertainment industry as a whole.

8. Dexameni, referring to the “arty square” of Kolonaki, the ruling class neighbourhood next to the Parliament was then a metonym for the bourgeois left.

9. proletarian neighbourhoods of Athens and Salonica at the time/ Kotzia is the city hall square of Athens where day-workers (builders etc) gathered before dawn to be picked by construction bosses.

10. proletarian neighbourhoods of Athens and Salonica at the time/ Kotzia is the city hall square of Athens where day-workers (builders etc) gathered before dawn to be picked by construction bosses.

|

|

|

Creating an Age Undreamed Of

The House Of Caesar

Yea — we have thought of royal robes and red. Had purple dreams of words we utterèd; Have lived once more the moment in the brain That stirred the multitude to shout again. All done, all fled, and now we faint and tire — The Feast is over and the lamps expire!

Yea — we have launched a ship on sapphire seas, And felt the steed between the gripping knees; Have breathed the evening when the huntsman brought The stiffening trophy of the fevered sport — Have crouched by rivers in the grassy meads To watch for fish that dart amongst the weeds. All well, all good — so hale from sun and mire — The Feast is over and the lamps expire!

Yet — we have thought of Love as men may think, Who drain a cup because they needs must drink; Have brought a jewel from beyond the seas To star a crown of blue anemones. All fled, all done — a Cæsar’s brief desire — The Feast is over and the lamps expire!

Yea — and what is there that we have not done, The Gods provided us ‘twixt sun and sun? Have we not watched an hundred legions thinned, And crushed and conquered, succorèd and sinned? Lo — we who moved the lofty gods to ire — The Feast is over and the lamps expire!

Yea — and what voice shall reach us and shall give Our earthly self a moment more to live? What arm shall fold us and shall come between Our failing body and the grasses green? And the last heart that beats beneath this head — Shall it be heard or unrememberèd? All dim, all pale — so lift me on the pyre — The Feast is over and the lamps expire!

ALL POETRY

![18302121_1225553447556038_1009971117_n[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/18302121_1225553447556038_1009971117_n1-199x300.jpg)

![lindsay[1]](https://hellenicpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/lindsay1.jpg)

Recent Comments