YOU WILL NEVER BE ALONE WITH A POET IN YOUR POCKET II

YOU WILL NEVER BE ALONE WITH A POET IN YOUR POCKET, JOHN ADAMS

ESPECIALLY A GREEK ONE, MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS

THIS WEBPAGE OF HELLENIC POETRY IS DEDICATED TO THE MOST MAGNIFICENT CREATURE IN THE WORLD

THE UNIQUE POUKA

Bewildered Wilderness

Return to the Wild: The Chris McCandless Story

Man is an animal that has gone wild. And this bewildered wilderness, has been wrongly termed by this same animal -which is totally out of control- A CIVILIZED SOCIETY.

MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2017

Certainly there is no hunting like the hunting of man and those who have hunted armed men long enough and liked it, never really care for anything else thereafter.

Ernest Hemingway, “On the Blue Water,” Esquire, April 1936

US author & journalist (1899 – 1961)

“The Hunter”

POETRY IS A TREE, A TALL ONE, IN THE MIDDLE OF THE DESERT OF THIS BEWILDERED WILDERNESS, WHERE THE LITLLE MAN, THE SCARED MAN, THE HUNTED MAN, CAN CLIMB, AND BE SAFE, AT LEAST FOR A WHILE…

MENELAOS KARAGIOZIS, HELLENIC POETRY, 2017

Nationality: Filipino. Born: Rosales, Pangasinan, 1924. Education: The University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Litt.B. 1949. Career: Staff member, Commonweal, Manila, 1947-48; assistant editor, United States Information Agency, U.S. Embassy, Manila, 1948-49; associate editor, 1949-57, and managing editor, 1957-60, Manila Times Sunday magazine, and editor of Manila Times annual Progress, 1958-60; editor, Comment quarterly, Manila, 1956-62; managing editor, Asia magazine, Hong Kong, 1961-62; information officer, Colombo Plan Headquarters, Ceylon, 1962-64; correspondent, Economist, London, 1968-69. Since 1965 publisher, Solidaridad Publishing House, and general manager, Solidaridad Bookshop, since 1966 publisher and editor, Solidarity magazine, and since 1967 manager, Solidaridad Galleries, all Manila. Lecturer, Arellano University, 1962, University of the East graduate school, 1968, and De La Salle University, 1984-86, all Manila; writer-in-residence, National University of Singapore, 1987; visiting research scholar, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, Japan, 1988. Consultant, Department of Agrarian Reform, 1968-79. Founder and national secretary, PEN Philippine Center, 1958. Awards: U.S. Department of State Smith-Mundt grant, 1955; Asia Foundation grant, 1960; National Press Club award, for journalism, 3 times; British Council grant, 1967; Palanca award, for journalism, 3 times, and for novel, 1981; ASPAC fellowship, 1971; Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio award, 1979; Cultural Center of the Philippines award, 1979; City of Manila award, 1979; Magsaysay award, 1980; East-West Center fellowship (Honolulu), 1981; International House of Japan fellowship, 1983; Outstanding Fulbrighters award, 1988, for literature; Cultural Center of the Philippines award, 1989, for literature.

PUBLICATIONS

Novels

The Pretenders. Manila, Solidaridad, 1962; published as The Samsons: The Pretenders; and, Mass, New York, Modern Library, 2000.

Tree. Manila, Solidaridad, 1978.

My Brother, My Executioner. Manila, New Day, 1979.

Mass. Amsterdam, Wereldvenster, 1982; London, Allen and Unwin, 1984; as Mis, Manila, Solidaridad, 1983.

Po-on. Manila, Solidaridad, 1985.

Ermita. Manila, Solidaridad, 1988.

Spiderman. Manila, Solidaridad, 1991.

Sin. Manila, Solidaridad, 1994; published as Sins, New York, Random House, 1996.

Dusk. New York, Modern Library, 1998.

Don Vincente: A Novel in Two Parts (contains Tree and My Brother, My Executioner). New York, Modern Library, 1999.

Short Stories

The Pretenders and Eight Short Stories. Manila, Regal, 1962.

The God Stealer and Other Stories. Manila, Solidaridad, 1968.

Waywaya and Other Short Stories from the Philippines. Hong Kong, Heinemann, 1980.

Two Filipino Women (novellas). Manila, New Day, 1982.

Platinum and Other Stories. Manila, Solidaridad, 1983.

Olvidon and Other Stories. Manila, Solidaridad, 1988.

Three Filipino Women (novellas) . New York, Random House, 1992.

Uncollected Short Stories

“The Chief Mourner” (serial), in Women’s Weekly (Manila), 11 May-10 July 1953.

“The Balete Tree” (serial), in Women’s Weekly (Manila), 4 March 1954-6 July 1956.

Poetry

Questions. Manila, Solidaridad, 1988.

Other

(Selected Works). Moscow, 1977.

A Filipino Agenda for the 21st Century. Manila, Solidaridad, 1987.

Conversations with F. Sionil Jose, edited by Miguel Bernad. Manila, Vera-Reyes, 1991.

In Search of the Word: Selected Essays of F. Sionil Jose. Manila, de la Salle University Press, 1998.

Editor, Equinox 1. Manila, Solidaridad, 1965.

Editor, Asian PEN Anthology 1. Manila, Solidaridad, 1966; New York, Taplinger, 1967.

Critical Studies:

F. Sionil Jose and His Fiction edited by Alfredo T. Morales, Manila, Vera-Reyes, 1990.

* * *

F. Sionil Jose holds two distinctions in Philippine writing in English, indeed in Philippine writing in general. He is the only writer who has produced a series of novels that constitute an epic imaginative creation of a century of Philippine life, and he is perhaps the most widely known abroad, his writings having been translated into more foreign languages than those of any other Filipino writer. (The only exception would be that greatest of all Filipino writers and patriots, Jose Rizal, martyred in the struggle against Spanish domination.)

We are introduced to the early world of Sionil Jose in Po-on. The earliest novel in terms of chronology, it is set in the later decades of the 19th century during the decaying years of the Spanish empire. The latter still retained some struggling remnants of its colonial civil services, including some manorial lords in the plains of central Luzon island, descendants of the Basque and Spanish-Catalan settlers, served by immigrants from the deep Ilocano country up north. In one scene a Basque grandee comes to the town of Rosales, when the settlement is still unorganized, and designates the limits of his domain with his whip.

After the Philippine revolution, which saw the change of colonial masters from Spanish to American, no significant change occurred in the feudal relations of the agrarian economy. In fact, free trade was instituted between the Philippines and the United States, benefiting the native landowners and their hirelings and the leaders of industry and their subalterns while impoverishing the tenants of the land and the laborers in small-scale industries. Such relationships are examined in Tree. Despite all the injustices they suffered during the American colonial regime, when war came in December 1941, the tenants and their leaders decided to fight the Japanese invaders as guerrillas, hoping that at the end of the war they would be afforded improved living conditions.

My Brother, My Executioner occurs at this point in Sionil Jose’s epic narrative. It deals with the activities of two half-brothers, one a dispossessed guerrilla. With more than enough property to keep his family in comfort, the bourgeois half-brother can afford to entertain liberal ideas and even consider embracing progressive ways, but his dispossessed half-brother avenges himself by destroying the more fortunate.

The master-servant, lord-slave relationship may also be found in the industrial world in Manila. One specific case is Antonio Samson in The Pretenders. Overcoming the disadvantages of rural birth, Samson manages to earn a doctorate at a prestigious New England university, afterwards planning to return to his hometown sweetheart, with whom he had fathered a child. Instead, he is snatched away by a powerful agro-industrial baron and married off to his socialite daughter. Samson is now made to move in elevated social circles and do work he had not prepared himself to do. He has frequent spats with his wife who, he discovers to his dismay, has been engaged in affairs with other men. Determined to end his shame, Samson throws himself under a train.

We are afforded a rich composite picture of the Philippines of the mid-to late twentieth century in Mass, which covers the years before and after the proclamation of martial law in 1972. A few of the old names reappear, but new characters emerge—student activists, women’s liberation movement followers, drug addicts, intellectuals. The major character is the bastard son of Antonio Samson, Pepe Samson, now living in the slums of Tondo. He is a faithful follower of a former anti-Japanese Huk (Communist rebel) commander now devoted to local affairs, and a student leader at a university in Manila. A reform movement that started with protest at the increase in oil prices becomes a struggle for human rights, student rights, tenant’s rights, women’s liberation, and eventually a heterogeneous mass of protests manipulated by fraudulent leaders. After the failure of the intended uprising, one of the dedicated characters decides to return to central Luzon to seek his roots and build anew.

Sins looks back on the history of the Philippines during much of the twentieth century through the eyes of the amoral Don Carlos Corbello, or C.C., who took part in that history and, on his deathbed, is reaping much of what he sowed. Dusk jumps back to the time of the Spanish-American War, whose Philippine theatre (as opposed to the Cuban theatre) is largely unknown to most Americans. In the course of Sionil Jose’s work, which calls to mind Balzac’s “Human Comedy” if on a smaller scale, we get an increasingly defined picture of Philippine history over more than a century. We are shown all kinds of people, from the moral cowards to the fiercely heroic, from the ferociously greedy to the selflessly philanthropic. In the face of all the tragic events in their lives, many of the people in Sionil Jose’s epic are still able to say “We shall overcome.”

JRANK

From the depth of good times

our loves greet us bitterlyYou’re not in love, you say, and you don’t remember.

And if your heart has filled and you shed the tears

that you couldn’t shed like you did at first,

you’re not in love and you don’t remember, even though you cry.Suddenly you’ll see two blue eyes

– how long it’s been! – that you caressed one night;

as though inside yourself you hear

an old unhappiness stirring and waking up.These memories of time past

will begin their danse macabre;

and like then, your bitter tear will

well up on your eyelid and fall.The eyes suspended – pale suns –

the light that thaws the frozen heart,

the dead loves that begin to stir,

the old sorrows that again ignite. . . .Νοσταλγία

Μεσ’ από το βάθος των καλών καιρών

οι αγάπες μας πικρά μας χαιρετάνε.Δεν αγαπάς και δε θυμάσαι, λες.

Κι αν φούσκωσαν τα στήθη κι αν δακρύζεις

που δε μπορείς να κλάψεις όπως πρώτα,

δεν αγαπάς και δε θυμάσαι, ας κλαίς.Ξάφνου θα ιδείς δυό μάτια γαλανά

-πόσος καιρός!- τα χάιδεψες μιά νύχτα,

και σα ν’ ακούς εντός σου να σαλεύει

μιά συφορά παλιά και να ξυπνά.Θα στήσουνε μακάβριο το χορό

οι θύμησες στα περασμένα γύρω,

και θ’ ανθίσει στο βλέφαρο σαν τότε

και θα πέσει το δάκρυ σου πικρό.Τα μάτια που κρεμούν – ήλιοι χλωμοί –

το φώς στο χιόνι της καρδιάς και λιώνει,

οι αγάπες που σαλεύουν πεθαμένες,

οι πρώτοι ξανά που άναψαν καημοί.INSPIRATIONALSTORIES

Hitler’s suicide and burial scene

|

|

|

Mao’s Great Leap Forward ‘killed 45 million in four years’

Mao Zedong, founder of the People’s Republic of China, qualifies as the greatest mass murderer in world history, an expert who had unprecedented access to official Communist Party archives said yesterday.

Speaking at The Independent Woodstock Literary Festival, Frank Dikötter, a Hong Kong-based historian, said he found that during the time that Mao was enforcing the Great Leap Forward in 1958, in an effort to catch up with the economy of the Western world, he was responsible for overseeing “one of the worst catastrophes the world has ever known”.

Mr Dikötter, who has been studying Chinese rural history from 1958 to 1962, when the nation was facing a famine, compared the systematic torture, brutality, starvation and killing of Chinese peasants to the Second World War in its magnitude. At least 45 million people were worked, starved or beaten to death in China over these four years; the worldwide death toll of the Second World War was 55 million.

Mr Dikötter is the only author to have delved into the Chinese archives since they were reopened four years ago. He argued that this devastating period of history – which has until now remained hidden – has international resonance. “It ranks alongside the gulags and the Holocaust as one of the three greatest events of the 20th century…. It was like [the Cambodian communist dictator] Pol Pot’s genocide multiplied 20 times over,” he said.

Between 1958 and 1962, a war raged between the peasants and the state; it was a period when a third of all homes in China were destroyed to produce fertiliser and when the nation descended into famine and starvation, Mr Dikötter said.

His book, Mao’s Great Famine; The Story of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, reveals that while this is a part of history that has been “quite forgotten” in the official memory of the People’s Republic of China, there was a “staggering degree of violence” that was, remarkably, carefully catalogued in Public Security Bureau reports, which featured among the provincial archives he studied. In them, he found that the members of the rural farming communities were seen by the Party merely as “digits”, or a faceless workforce. For those who committed any acts of disobedience, however minor, the punishments were huge.

State retribution for tiny thefts, such as stealing a potato, even by a child, would include being tied up and thrown into a pond; parents were forced to bury their children alive or were doused in excrement and urine, others were set alight, or had a nose or ear cut off. One record shows how a man was branded with hot metal. People were forced to work naked in the middle of winter; 80 per cent of all the villagers in one region of a quarter of a million Chinese were banned from the official canteen because they were too old or ill to be effective workers, so were deliberately starved to death.

Mr Dikötter said that he was once again examining the Party’s archives for his next book, The Tragedy of Liberation, which will deal with the bloody advent of Communism in China from 1944 to 1957.

He said the archives were already illuminating the extent of the atrocities of the period; one piece of evidence revealed that 13,000 opponents of the new regime were killed in one region alone, in just three weeks. “We know the outline of what went on but I will be looking into precisely what happened in this period, how it happened, and the human experiences behind the history,” he said.

Mr Dikötter, who teaches at the University of Hong Kong, said while it was difficult for any historian in China to write books that are critical of Mao, he felt he could not collude with the “conspiracy of silence” in what the Chinese rural community had suffered in recent history.

INDEPENDENT

Η ΕΦΗΜΕΡΙΔΑ

|

|

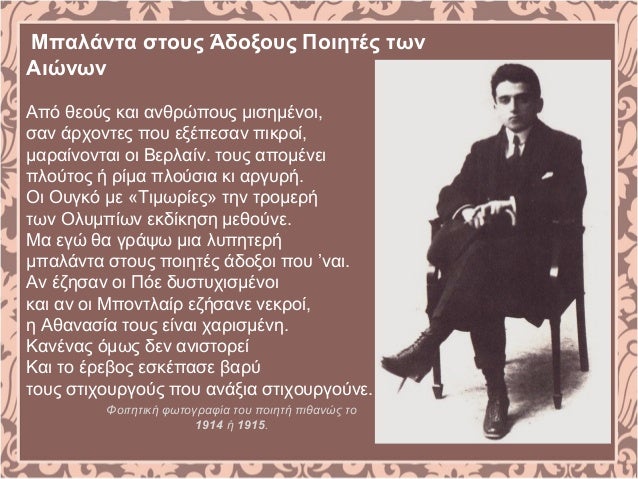

ΗΡΑΚΛΕΙΤΟΣ

53. – Περὶ φύσεως (Απόσπασμα 1, 123, 107, 93, 2, 51, 101, 53, 60, 30, 94, 119, 43, 44 Diels-Kranz)

Περί φύσεως

Το μοναδικό έργο που έγραψε ο Ηράκλειτος από την Έφεσο ήταν σε πεζό λόγο και φέρει, όπως και τα έργα των άλλων φυσικών φιλοσόφων, τον (πιθανότατα νόθο) τίτλο Περί φύσεως. Κύριο χαρακτηριστικό του ύφους του είναι ο συνειδητά αφοριστικός, εύκολα απομνημονεύσιμος αλλά συνάμα και δυσνόητος λόγος, που του έδωσε ήδη στην αρχαιότητα των χαρακτηρισμό του “σκοτεινού”. Βασικά στοιχεία της διδασκαλίας του: (1) Οι άνθρωποι πρέπει να γνωρίσουν τον Λόγο (πιθανώς σημαίνει: βασική ενοποιητική αρχή ή “δομικό σχέδιο” του κόσμου και των πραγμάτων), τον οποίο κατέχει ο ίδιος ο φιλόσοφος. (2) Ο κόσμος μεταβάλλεται ασταμάτητα. (3) Ο κόσμος είναι μια αιώνια φωτιά (η φωτιά αποτελεί σύμβολο της αέναης μεταβολής). (4) Η ισορροπία του κόσμου διατηρείται μόνον με τον συνεχή ανταγωνισμό των αντίθετων· ο πόλεμος είναι πατέρας και βασιλιάς όλων. Από τα σωζόμενα αποσπάσματα συνάγεται ότι το έργο είχε τριμερή διάρθρωση: στο πρώτο μέρος παρουσιαζόταν η θεωρία για το βαθύτερο νόημα των πραγμάτων, δηλαδή η “θεωρία περί Λόγου”, στο δεύτερο η “θεωρία της φωτιάς”, ενώ το τρίτο περιλάμβανε αποφάνσεις για ηθικά και πολιτικά ζητήματα (από το πρώτο μέρος προέρχονται τα αποσπάσματα α-θ, από το δεύτερο τα ι-ια, ενώ από το τρίτο τα ιβ-ιδ).

1 Το απόσπασμα θεωρείται από τους μελετητές ότι προέρχεται από το προοίμιο του έργου.

2 Το νόημα της πρότασης είναι ότι η αληθινή δομή των πραγμάτων δεν είναι μεν απρόσιτη στην ανθρώπινη γνώση, κρύβεται ωστόσο βαθιά μέσα στα ίδια τα πράγματα.

3 Με τη λέξη “άρχοντας” (ἄναξ) εννοείται ο Απόλλων. Όπως το μαντείο των Δελφών, έτσι και η φύση δίνει μόνο “σημάδια”, από τα οποία εκκινώντας μπορεί να κατανοήσει κανείς το νόημα των πραγμάτων.

4 Στο πλαίσιο της θεμελιώδους διδασκαλίας του για την ενότητα των αντιθέτων ο Ηράκλειτος εκφράζει στο απόσπασμα αυτό την άποψη του για την σύνθεση των αντιθέτων, η οποία οδηγεί στην αρμονία. Ως παραδείγματα χρησιμοποιούνται το τόξο και η λύρα. Στις περιπτώσεις και των δύο οργάνων ασκούνται αντίρροπες δυνάμεις (προς το εξωτερικό αρχικά και προς το εσωτερικό του οργάνου κατόπιν), οι οποίες όμως στο τέλος εξισορροπούνται σε μια αρμονική κατάσταση

5 Το βάρος πέφτει στο αντικείμενο “τον εαυτό μου”. Πβ. την γνωστή προτροπή του μαντείου των Δελφών: γνῶθι σαυτόν.

6 Ο πόλεμος παρουσιάζεται εδώ με τα χαρακτηριστικά του Δία. “Θεοί” γίνονται οι νεκροί του πολέμου, οι οποίοι ως ἥρωες πια απολαμβάνουν θεϊκές τιμές.

7 Στο απόσπασμα εκφράζεται η αντίληψη για τη βαθύτερη ενότητα των αντιθέτων: ο ίδιος δρόμος μπορεί να χαρακτηριστεί “ανήφορος” ή “κατήφορος”, ανάλογα με το σημείο στο οποίο βρισκόμαστε.

8 Ερινύες: αμείλικτες θεότητες της εκδίκησης, ιδιαίτερα για εγκλήματα που ξεφεύγουν από τα ανθρώπινα όρια. Δίκη: προσωποποίηση της δικαιοσύνης. Το νόημα του αποσπάσματος: ακόμη και ο Ήλιος (θεός, προσωποποίηση ενός φυσικού φαινομένου με χαρακτηριστική κανονικότητα ως προς την εμφάνισή του στους ανθρώπους) υπόκειται στους νόμους της κοσμικής τάξης· έστω και αν προς στιγμήν (π.χ. σε μια έκλειψη ηλίου) τους παραβαίνει, οι Ερινύες αποκαθιστούν την κοσμική τάξη.

9 Ο όρος δαίμων, που χρησιμοποιείται στο πρωτότυπο, δήλωνε στην αρχαιότητα την (απρόσωπη) θεϊκή δύναμη που εκδηλώνεται σε μια συγκεκριμένη περίπτωση. Στην αρχαϊκή ποίηση οι δαίμονες θεωρούνται συχνά από τους ανθρώπους υπεύθυνοι για όσα απροσδόκητα και πέρα από τη λογική τούς συμβαίνουν. Ο Ηράκλειτος καθιστά εδώ υπεύθυνο για την τύχη του κάθε ανθρώπου αποκλειστικά τον χαρακτήρα του

ΚΕΝΤΡΟ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΓΛΩΣΣΑΣ

Tony Hancock Face to Face Interview Part 01

|

|

|

NASA’s Kepler Confirms 100+ Exoplanets During Its K2 Mission | NASA

Hans Frank

One of Hitler’s top lieutenants, Governor-General of occupied Poland. A war criminal and a mass murderer, who was executed in Nuremburg for his presiding over the extermination of Poles and Jews.

Hans Frank was Reich Minister without portfolio, leader of the National Socialist Lawyers Bund 1933-1942, member of the Reichstag, President of the International Chamber of Law 1941-42 and of the Academy of German Law. SS-Obergruppenführer – and Governor-General of the occupied Polish Territories October 1939-1945.

Hans Frank in Poland

During WWII the successful annexation of Austria and the successful conquest, first of Czechoslovakia and then of Poland opened up vast territories of available space to Hitler for colonization and resettlement. It also brought into focus the “Jewish Problem” and the quest for a “Final Solution.”

Hans Frank, the Nazi butcher

The General Government, headed by Hans Frank, seemed to offer the greatest potential for lebensraum. First, however, there was the problem of clearing the area of Polish nationals and the several million Jews who lived in the area.

Horrors of Holocaust

In a speech December 16, 1941, Hans Frank said:”We cannot shoot these 3.5 million Jews, we cannot poison them, but we will take measures that will somehow lead to successful destruction; and this in connection with large-scale procedures which are to be discussed in the Reich, the Government-General must become as free of Jews as the Reich …..We must destroy the Jews wherever we find them and wherever it is at all possible, in order to maintain the whole structure of the Reich… “

Under Hans Frank`s ruthless rule, the nation of Poland disappeared as a national entity and became a slave state, with the murder of Poland’s leaders, educated elite and clergy, and the extermination of nearly all Poland’s Jews.

Auschwitz

Bergen-Belsen Belzec Sobibor Treblinka

During WWII over half a million fighting Poles , and 6 million civilians died. Approximately 5,400,000 were the victims of prisons, death camps, executions, annihilation of ghettos, starvation and ill treatment. So many Poles were sent to concentration camps that virtually every family had someone close to them who had been tortured or murdered there.

There were one million war orphans and over half a million invalids …

Hans Frank:”We must destroy the Jews wherever we find them …”

Hans Frank converted to Roman Catholicism after his arrest, and at the Nuremberg trial he declared: “A thousand years will pass and the guilt of Germany will not be erased.”

Hans Frank at Nuremberg

Hans Frank was found guilty as a war criminal and sentenced to death by hanging. He was the only one of the condemned to enter the chamber with a smile on his countenance. He answered to his name quietly and when asked for any last statement, he replied in a low voice that was almost a whisper:” …I ask God to accept me with mercy”.

AUSCHWITZ

Could alien megastructure be reason this star is getting dimmer? (DAILY EXPRESS)

ADOLF HITLER

“If you win, you need not have to explain…If you lose, you should not be there to explain!”

“If you tell a big enough lie and tell it frequently enough, it will be believed.”

“Do not compare yourself to others. If you do so, you are insulting yourself.”

“if you want to shine like sun first you have to burn like it.”

“And I can fight only for something that I love, love only what I respect, and respect only what I at least know.”

“Anyone can deal with victory. Only the mighty can bear defeat.”

“Think Thousand times before taking a decision But – After taking decison never turn back even if you get Thousand difficulties!!”

“Those who want to live, let them fight, and those who do not want to fight in this world of eternal struggle do not deserve to live.”

GOODREADS

“When diplomacy ends, War begins.”

“The man who has no sense of history, is like a man who has no ears or eyes”

“Only the Jew knew that by an able and persistent use of propaganda heaven itself can be presented to the people as if it were hell and, vice versa, the most miserable kind of life can be presented as if it were paradise. The Jew knew this and acted accordingly. But the German, or rather his Government, did not have the slightest suspicion of it. During the War the heaviest of penalties had to be paid for that ignorance.– Mein Kampf, Chapter 10”

“The stronger must dominate and not mate with the weaker, which would signify the sacrifice of its own higher nature. Only the born weakling can look upon this principle as cruel, and if he does so it is merely because he is of a feebler nature and narrower mind; for if such a law did not direct the process of evolution then the higher development of organic life would not be conceivable at all.”

“He alone, who owns the youth, gains the future.”

“Reading is not an end to itself, but a means to an end.”

“I use emotion for the many and reserve reason for the few.”

“Words build bridges into unexplored regions.”

“The victor will never be asked if he told the truth. ”

“The receptivity of the masses is very limited, their intelligence is small, but their power of forgetting is enormous. In consequence of these facts, all effective propaganda must be limited to a very few points and must harp on these in slogans until the last member of the public understands what you want him to understand by your slogan.”

“The art of reading consists in remembering the essentials and forgetting non essentials.”

“To conquer a nation, first disarm its citizens.”

“The only preventative measure one can take is to live irregularly.”

― Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf

“Instruction in world history in the so-called high schools is even today in a very sorry condition. Few teachers understand that the study of history can never be to learn historical dates and events by heart and recite them by rote; that what matters is not whether the child knows exactly when this battle or that was fought, when a general was born, or even when a monarch (usually a very insignificant one) came into the crown of his forefathers. No, by the living God, this is very unimportant. To ‘learn’ history means to seek and find the forces which are the causes leading to those effects which we subsequently perceive as historical events.”

“If freedom is short of weapons, we must compensate with willpower.”

“Kill, Destroy, Sack, Tell lie; how much you want after victory nobody asks why?– uncited source”

“The very first essential for success is a perpetually constant and regular employment of violence.”

“The great strength of the totalitarian state is that it forces those who fear it to imitate it.”

“As in everything, nature is the best instructor.” ―

“The state must declare the child to be the most precious treasure of the people. As long as the government is perceived as working for the benefit of the children, the people will happily endure almost any curtailment of liberty and almost any deprivation.”

― Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf

“Humanitarianism is the expression of stupidity and cowardice.”

GOODREADS

Liberty, once lost, is lost forever.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Abigail Adams, Jul. 17, 1775

There is nothing which I dread so much as a division of the republic into two great parties, each arranged under its leader, and concerting measures in opposition to each other. This, in my humble apprehension, is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil under our Constitution.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Jonathan Jackson, Oct. 2, 1789

A government of laws, and not of men.

JOHN ADAMS, Novanglus Essays, No. 7

The only maxim of a free government ought to be to trust no man living with power to endanger the public liberty.

JOHN ADAMS, Notes for an oration at Braintree, Spring 1772

Our obligations to our country never cease but with our lives.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Benjamin Rush, Apr. 18, 1808

Laws for the liberal education of youth, especially of the lower class of people, are so extremely wise and useful, that, to a humane and generous mind, no expense for this purpose would be thought extravagant.

Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.

JOHN ADAMS, Argument in Defense of the British Soldiers in the Boston Massacre Trials, Dec. 4, 1770

NOTABLE QUOTES

Let every sluice of knowledge be opened and set a-flowing.

We ought to consider what is the end of government, before we determine which is the best form. Upon this point all speculative politicians will agree, that the happiness of society is the end of government, as all Divines and moral Philosophers will agree that the happiness of the individual is the end of man. From this principle it will follow, that the form of government which communicates ease, comfort, security, or, in one word, happiness, to the greatest number of persons, and in the greatest degree, is the best.

The jaws of power are always open to devour, and her arm is always stretched out, if possible, to destroy the freedom of thinking, speaking, and writing.

JOHN ADAMS, A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law

As to the history of the revolution, my ideas may be peculiar, perhaps singular. What do we mean by the Revolution? The war? That was no part of the revolution; it was only an effect and consequence of it. The revolution was in the minds of the people, and this was effected … before a drop of blood was shed.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Thomas Jefferson, Aug. 24, 1815

It is more important that innocence be protected than it is that guilt be punished, for guilt and crimes are so frequent in this world that they cannot all be punished. But if innocence itself is brought to the bar and condemned, perhaps to die, then the citizen will say, ‘whether I do good or whether I do evil is immaterial, for innocence itself is no protection,’ and if such an idea as that were to take hold in the mind of the citizen that would be the end of security whatsoever.

JOHN ADAMS, attributed, John Adams: His Words

While all other Sciences have advanced, that of Government is at a stand; little better understood; little better practiced now than three or four thousand years ago.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Thomas Jefferson, Jul. 9, 1813

The consequences arising from the continual accumulation of public debts in other countries ought to admonish us to be careful to prevent their growth in our own.

JOHN ADAMS, First Address to Congress, Nov. 23, 1797

Abuse of words has been the great instrument of sophistry and chicanery, of party, faction, and division of society.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to J. H. Tiffany, Mar. 31, 1819

Nip the shoots of arbitrary power in the bud, is the only maxim which can ever preserve the liberties of any people.

JOHN ADAMS, Novanglus Essays, No.

The prospect is chilling, on every Side. Gloomy, dark, melancholy, and dispiriting. When and where will the light spring up?

JOHN ADAMS, diary, Sep. 16, 1777

The fundamental article of my political creed is that despotism, or unlimited sovereignty, or absolute power, is the same in a majority of a popular assembly, an aristocratical council, an oligarchical junto, and a single emperor. Equally arbitrary, cruel, bloody, and in every respect diabolical.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Thomas Jefferson, Nov. 13, 1815

Thanks to God that he gave me stubbornness when I know I am right.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Edmund Jenings, 1782

I had heard my father say that he never knew a piece of land run away or break.

JOHN ADAMS, Autobiography

Old minds are like old horses; you must exercise them if you wish to keep them in working order.

JOHN ADAMS, attributed, Looking Toward Sunset: From Sources Old and New, Original and Selected

I read my eyes out and can’t read half enough…. The more one reads the more one sees we have to read.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Abigail Adams, Dec. 28, 1794

The science of government it is my duty to study, more than all other sciences; the arts of legislation and administration and negotiation ought to take the place of, indeed exclude, in a manner, all other arts. I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. Our sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history and naval architecture, navigation, commerce and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry and porcelain.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Abigail Adams, May 12, 1780

The right of a nation to kill a tyrant, in cases of necessity, can no more be doubted, than to hang a robber, or kill a flea. But killing one tyrant only makes way for worse, unless the people have sense, spirit and honesty enough to establish and support a constitution guarded at all points against the tyranny of the one, the few, and the many.

JOHN ADAMS, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government

We think ourselves possessed, or, at least, we boast that we are so, of liberty of conscience on all subjects, and of the right of free inquiry and private judgment in all cases, and yet how far are we from these exalted privileges in fact! There exists, I believe, throughout the whole Christian world, a law which makes it blasphemy to deny or doubt the divine inspiration of all the books of the Old and New Testaments, from Genesis to Revelations. In most countries of Europe it is punished by fire at the stake, or the rack, or the wheel. In England itself it is punished by boring through the tongue with a poker. In America it is not better; even in our own Massachusetts, which I believe, upon the whole, is as temperate and moderate in religious zeal as most of the States, a law was made in the latter end of the last century, repealing the cruel punishments of the former laws, but substituting fine and imprisonment upon all those blasphemers upon any book of the Old Testament or New. Now, what free inquiry, when a writer must surely encounter the risk of fine or imprisonment for adducing any argument for investigating into the divine authority of those books? Who would run the risk of translating Dupuis? But I cannot enlarge upon this subject, though I have it much at heart. I think such laws a great embarrassment, great obstructions to the improvement of the human mind. Books that cannot bear examination, certainly ought not to be established as divine inspiration by penal laws. It is true, few persons appear desirous to put such laws in execution, and it is also true that some few persons are hardy enough to venture to depart from them. But as long as they continue in force as laws, the human mind must make an awkward and clumsy progress in its investigations. I wish they were repealed. The substance and essence of Christianity, as I understand it, is eternal and unchangeable, and will bear examination forever, but it has been mixed with extraneous ingredients, which I think will not bear examination, and they ought to be separated.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Thomas Jefferson, Jan. 23, 1825

Liberty, according to my metaphysics, is an intellectual quality; an attribute that belongs not to fate nor chance. Neither possesses it, neither is capable of it. There is nothing moral or immoral in the idea of it. The definition of it is a self-determining power in an intellectual agent. It implies thought and choice and power; it can elect between objects, indifferent in point of morality, neither morally good nor morally evil. If the substance in which this quality, attribute, adjective, call it what you will, exists, has a moral sense, a conscience, a moral faculty; if it can distinguish between moral good and moral evil, and has power to choose the former and refuse the latter, it can, if it will, choose the evil and reject the good, as we see in experience it very often does.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to John Taylor, 1814

The turpitude, the inhumanity, the cruelty, and the infamy of the African commerce in slaves have been so impressively represented to the public by the highest powers of eloquence that nothing that I can say would increase the just odium in which it is and ought to be held. Every measure of prudence, therefore, ought to be assumed for the eventual total extirpation of slavery from the United States.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to T. Robert J. Evans, June 8, 1819

Power always sincerely, conscientiously, de tres bon foi, believes itself right. Power always thinks it has a great soul and vast views, beyond the comprehension of the weak.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to Thomas Jefferson, Feb. 2, 1816

My fixed principle never to be the tool of any man, nor the partisan of any nation, would forever exclude me from the smiles and favors or courts.

JOHN ADAMS, diary, 1

Let the human mind loose. It must be loose. It will be loose. Superstition and dogmatism cannot confine it.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to John Quincy Adams, Nov. 13, 1816

You will never be alone with a poet in your pocket.

JOHN ADAMS, letter to John Quincy Adams, May 14, 1781

A Surrealist’s Tribulations in the Difficult Year of 1935

With Blast-Furnace (1935), Andreas Embiricos undoubtedly became the first surrealist poet in Greece. Even though precedence cannot in and of itself act as a basis for evaluation, in this particular case, all Greek surrealists grant first place to Embiricos by dint of the radiance his work and personality has had on them. Already by 1938, when the volume Surrealism was published (being a kind of collective appearance of Greek surrealists) Embiricos was officially granted first place in the book (he translated Breton, the ‘founder of surrealism’), whilst the last, but certainly not least, place was given to Engonopoulos, who translated the other uncompromising dadaist, Tzara. Today we are in a position to observe that by having Embiricos and Engonopoulos open and close the volume on Surrealism, we are offered a good picture of the surrealist movement during the inter-War years. Indeed, these two poets, through their work and overall attitude, wrung the relatively loose (in terms of size) literary life of our country, certainly not with the aim of strangling it (utterly harmless as they were) but in order to rid it of its polluted effusions.Year One for Greek surrealism therefore starts in 1935, with Blast-Furnace. There follow: Odysseus Elytis’ Orientations (Ta Nea Grammata review, vol. 7-8, July-August 1936); A Contract with Demons, by Nikos Kalamaris (Randos), in November 1936; Nikos Engonopoulos’ Do Not Distract the Driver, October 1938; and, Nikos Gatsos’ Amorgos, in 1943. (I choose to draw a line here because after this date come the surrealists of the next generation who, in my opinion, are poets of different problematics and variant experiences.)If surrealism marks a radical break from a traditional poetic past and, possibly, a rhetoric rupture with the prevailing conformist spirit (whereas in all other modernistic styles of writing only a strong deviation from it is witnessed), to think that Ta Nea Grammata of 1935 covers the whole spectrum of new poetry would be fallacious. After all, if we need more proof and find that what Elytis wrote in his Cards Laid Open about the spirit that pervaded the publishers of the review is not enough, we only need to look at the poems that were published in the 1935 and 1936 volumes of the review; all the poems by Elytis, Saradaris and Seferis, and the translations of Eliot and Pound in the 1935 volume, as well as all the poems by Antoniou, Drivas, Eleftheriou (aka Ritsos), Elytis, Saradaris, and the second translation of Eliot’s Wasteland in the 1936 volume leave surrealism out (with the exception of the second poems of Elytis, which, however, belong to a more moderate and eclectic surrealism).

Embiricos reminisces about his lecture in 1935: “Katsibalis was against, and Karandonis was wary.”* The fact remains that there is no critique on Blast-Furnace in Ta Nea Grammata, with the exception of a four-line comment by Karandonis (Feb 1936, p. 167) when he takes stock of the books published during 1935; in this he defers the problem of dealing with the book for a future issue.

Embiricos will find a publication to shelter him for the first time in Ta Nea Grammata of May 1937 (vol. 5), in which he publishes the first six poems of the series ‘The Vertebrae of the City’, from Inner Land. In April-May 1938 (vols. 4-5), the remaining eight poems from that series are printed, whilst in spring 1940 (vol. 1) he publishes the first nineteen poems of the series ‘Altamira’s Tentacle’ (Inner Land), as well as three texts from the Writings from the series titled ‘Fiction’.

Can it be pure chance that the poem that was omitted from the ‘Vertebrae’ series was ‘A Maiden’s Advantage Is the Joy of Her Man’? Or that the three poems from Castles of the Wind, the three poems from the series ‘The Tenderness of Breasts’, the four poems from Prouthos’ Birds, all of which were written before the ‘Vertebrae’ series, get to be published only in May 44 (vol. 3, new period for the review), in spite of the fact that in the midst of the radical climate of the Occupation, general attitudes had changed and the receptivity of both the public and the specialists had grown?

By these hopefully not too pedantic details I wish to argue that, during the later years of the inter-War period, Embiricos’ surrealist mode of writing was expressed within a limited circle and was met with scepticism even by the supposedly most avant-garde review of the time, Ta Nea Grammata. Uncompromising surrealism, expressed through its two main proponents, still played only a fairly marginal role, and was assimilated very gradually, pari passu with the increase in the production of poetic material by more moderate representatives of modernistic writing. The writings of these more moderate writers leaned (subtly and unconsciously) towards the surrealists, accepting the validity of such audacious writing, since the criteria by which the critics judged poetic phenomena had been altered not because of the forms of surrealism but because of the lessons it had to teach. May I remind you that 1935 did not simply have a month of hardships – the entire year was a full of hardships. The Plastiras movement, possibly an attempt to curb the reactionary tendencies of the regime, ended up in Kondylis’ dictatorship (sending not only Glinos into exile, but also Varnalis, who was, politically, harmless). This in turn led to the falsified referendum and Glucksburg’s restoration, who made circumstances secure for himself on August 4th.

If there is any merit in my hypothesis that Embiricos’ lecture and Blast-Furnace in 1935 are gestures of revolutionary ilk (this being the reason why no one embraces such a hypothesis), then we may move on to question yet another myth. It has been maintained that Greek surrealism is stunted compared to the French surrealist movement; that Greek surrealists were not political revolutionaries as well, like their French like-minded counterparts. Although Embiricos, just like Elytis and Engonopoulos, was influenced by the Left for a certain period of time, let us ignore this so that we may proceed with our argument. What kind of liberties was the Greek regime willing to put up with and what kind of sensibilities did the Greek intellectual public posses at the time? In what kind of environment could an intellectual Left ideology, with open political views, take root and develop? Simera review barely lasted over a year (1933-1934). The coterie of Young Pioneers felt suffocated by the review’s political expediencies. People’s evaluations of the 1917 experiment were shattered by the Moscow trials. At an international level, too, the allure that the USSR held for intellectual and artistic circles in the ’20s had begun to visibly wane in the ’30s. In such a climate, any artist who wished to maintain his intellectual independence (which is arguably tantamount to the need for an honest relationship with the tools of his craft) came up against difficulties with regard to his political choices.

Be that as it may, Embiricos cannot be politically pigeonholed in the Left. Does that mean he is to be slotted in the Right? After all, based on what evidence does his work serve the ideology of the Right of the inter-War and post-War era? Merely by dint of its lacking any political dimensions? How many scintillas of political scope does Breton’s work, or that of his entourage of surrealists, have? Such categorisations are extremely facile and very impressive to boot, but only go that far.

I mentioned the ideology that Greece’s state and suprastate authorities promoted in those years, but it falls outside the scope of this treatise to delineate it in depth. I shall limit myself to suggesting that this ideology climaxed in the proclamation of the Third Hellenic Civilisation by dictator Metaxas and his theoretician Nikoloudis. Palamas and his fellow-poets, with their worship of Greece, are as responsible for the way it was falsified by the regime as Nietzsche was for the way his work was read by Hitler’s followers. In spite of this falsification, the prevailing ‘Palamic’ climate fostered constructive work (notice how suddenly we have texts such as ‘The Twelve Words of the Gypsy’ or ‘Satirical Exercises’), whilst, from a political perspective, it is expressed with the 1909 events, and the liberating wars, although after 1922 it loses its social underpinnings. It is not surprising that another intellectual tendency, embodied by Kavafis, began to have an effect on our literary life. Kavafis was already known since 1903, thanks to Ksenopoulos, but became prominent, to some extent, only after 1922, and much more broadly after 1935. Varnalis, a revolutionary in his mature age, was raised in the Palamic tradition yet struggled to reverse it, but to little effect. Kariotakis, who experienced this situation at a younger age, reacted in a more direct and nonconformist manner. As for his fellow-travellers, they remained trapped elsewhere, even though they, too, opposed this tradition.

Embiricos, five years younger than Kariotakis and full of a different kind of potential (a cosmopolite, in all truth) began, admittedly, with Palamic poems, but almost immediately went on to experiment by searching for another function for poetic language. From that moment on, during the 1927-31 period – which was critical for French surrealism – Embiricos’ shift from psychoanalysis, which he had been studying, to surrealist exercises came as a totally natural matter of course. In fact, if we take into account that Embiricos is one of the most prolific Greek writers, which means a considerable ease at writing, the automatic writing of his first poems became a genre and was obviously within his capacities.

POETRYINTERNATIONAL

The 1935 edition of Blast Furnace includes 63 poems; these poems are only a selection of what he had written “before 1935 […] with the method of automatic writing”. I do not know the criteria that Embiricos used to select eight poems out of the 63 for the phonograph record Embiricos reads Embiricos. In other words, we have no way of knowing whether he considered them to be his best or the ones more digestible for the public.

Let us choose a different perspective to look at this poetic harvest, which has endured a great many attacks. Personally, I have no reason to doubt the claim that all 63 poems were written ‘automatically’; yet I do leave it open to question whether behind even the most automatic of writing lie certain inhibitions. I believe that this would more likely than not be corroborated by any psychoanalyst. Choosing from the first 15 poems, I quote only the verses that contain passages of a clearly erotic nature. I beg and hope that the reader will not limit him to these excerpts but will look up the entire poems.

From poem number 1 (Galaxias editions, p. 9): “and oblivion […] lasts like a snare in the shell of the systematic narration of breasts”.

From poem number 3 (p. 11): “and at the refectory he was allowed […] a symbiosis with the young ladies in the company of dancing seafarers traversing the present tense”.

From poem number 4 (p. 12): “and the skins of pears that prefer the erection of the penis to the lulling clouds of byways of chemical repudiation and discovery of excrement and jewellery”.

From poem number 5 (p. 13): “and the glow of her immaculate breasts came alive word for word, and almost diagonally”.

From poem number 6 (p. 14): “… A helix twists within us cutting the throats of cockerels and the tits of every redundant fibula”.

From poem number 7 (p. 15): “Only more freedom was given to the free, and the pain of yesternight’s orgy-monger subsided”.

Allow me to skip the intervening poems and quote poem number 15 (p. 23) in its entirety:

Earlier than even the copulation she would indulge in tomorrow, the suffering apex of the ultimate mountain range lowered her eyelids to receive the gifts of automatic gyrations. Thirty members of a hermaphrodite conversation confiscated the irremediable copse with pomp and fanfare whilst the monkey-parade brimmed with lobsters, mostly, and elegant lemonade in cartons. Since however no one lifted the net which others in this country call a Bavarian protrusion the blade of fabrics was torn in half and out forever came the dean of holy mania indistinguishable from the bird that pops out of a sock.

(‘The welcome of the peddlers’)In all these excerpts, only one phrase in poem 4 flouts the conventions of the time, and even that is borrowed from scientific terminology. Knowing as we do the degree of outspokenness that Embiricos indulged in in his later writings, we may safely argue that what the automatic writing of his first poems brought to the surface from the depths of his unconscious were censored images – even though the brazenness of his style would probably have allowed for greater liberties, given that it was the style itself that was the most disturbing. Could this be due to bourgeois prudence? Could it be a consequence of his bourgeois upbringing? Yet the bourgeois had for at least over a century already allowed themselves much greater liberties in this area (cf. Communist Manifesto, 1848). Personally I believe that, in all likelihood, it is a case of inhibitions due to his upbringing in the specific milieu in which he was raised. Upbringing is not always determined by class, since we may encounter close- or open-minded types of upbringing in all social classes. A psychoanalyst’s feedback would be most enlightening at this juncture. Let us then be patient until somebody takes on the task.

I find Embiricos’ own avowal quite revealing. It dates back to the same period we have been discussing:

In 1931, I returned to Greece, and worked at our family business, a shipyard. In 1935, I resigned my post as a director. A short time before that there had been strikes, which had made me feel ill at ease. On one hand I didn’t want to prove inconsistent with my principles, but on the other I didn’t want to disappoint my father, to whom I was deeply grateful. Therefore I resigned and devoted myself definitively to literature and psychoanalysis.”

(From the same interview given to Andromachi Skarpalezou.)Be that as it may, with Blast Furnace we find ourselves at the birth of a genre of writing and the beginning of a self-psychoanalysing individual’s expression, as he becomes more and more liberated as times goes by – if we judge by his later production, at least. His tone when calling for ‘absolute freedom’ grew steadily in intensity, so much so that he now has to keep his writings locked up in drawers because of other people’s inhibitions. As for his abandoning automatic writing, in no way was it some sort of retraction but it arose from a state of maturity, which became manifest for the entire surrealist movement already by the time of Breton’s second manifesto.

Thus, in the difficult year of 1935, Seferis and Embiricos, each working on two divergent curves, respectively published: “We have no rivers we have no wells we have no springs . . .” (Novel, X). “We have no quince . . .” (Blast Furnace, ‘Whitewash’).

About one to two hundred readers read them and interpreted them to the best of their abilities.

*Interview given to Andromachi Skarpalezou, March 1967. Vd. Iridanos review, vol. 4, Feb-Mar 1976.

From Consecutive Readings of Greek Surrealists, also published in To Dentro literary review, No 1, Sept. – Oct. 1979)

© Alexandros Argyriou

Κάθε λογικός άνθρωπος έχει κάποτε σκεφτεί την αυτοκτονία έγραψε ο Αλμπέρ Καμύ,

Αντόνιο ντι Μπενεντέττο – Οι αυτόχειρες

Ένας αργεντινός συγγραφέας άγνωστος στις ελληνικές εκδόσεις· ένας λογοτέχνης για τον οποίο εκφράστηκαν ο Μπόρχες και ο Κορτάσαρ εκφράστηκαν με τα καλύτερα λόγια (ο πρώτος μίλησε για σελίδες που τον συγκίνησαν, ο δεύτερος για ένα σπάνιο παράδειγμα μυθιστοριογράφου που δεν χρειάζεται να καταφύγει στην ιδεολογική ανασύνθεση του παρελθόντος, καθώς ζει το παρελθόν και μας φέρνει κοντά σε εμπειρίες και συμπεριφορές που διατηρούν άθικτο τον παραλογισμό τους)· ένας αγωνιστής κατά του φασισμού, καθώς το 1976, λίγες ώρες μετά την επιβολή της δικτατορίας, συνελήφθη, και αφέθηκε ελεύθερος έπειτα από ένα χρόνο φυλάκισης και βασανιστηρίων, χάρη στην πίεση Αργεντινών και Ευρωπαίων συγγραφέων, όπως ο Ερνέστο Σάμπατο και ο Χάινριχ Μπελ. Ο καθένας από τους παραπάνω λόγους υπήρξε αρκετός για να ενδιαφερθώ άμεσα για αυτό το βιβλίο, μαζί μ’ ένα ακόμα στοιχείο, που δεν είναι άλλο από το ίδιο το θέμα: η αυτοκτονία ως κεντρικό θέμα όχι ενός δοκιμίου αλλά ενός μυθιστορήματος!

Με ποιο τρόπο όμως μπορεί να αποτελέσει η αυτοχειρία το κέντρο ενός μύθου; Εδώ υπάρχει ως αστυνομικό μυστήριο, ως προσωπική οικογενειακή ιστορία, ως ιδιότυπος κατάλογος περιπτώσεων αυτοχειρίας, ως παράθεση των απόψεων πάνω στο θέμα και ως αντικείμενο στοχασμού. Μέτοχος όλων των παραπάνω πεδίων είναι ο ανώνυμος αφηγητής, που ως δημοσιογράφος αναλαμβάνει να ερευνήσει τις περιπτώσεις τριών ανώνυμων αυτοχείρων: οι φωτογραφίες των αναχωρητών βρίσκονται σ’ ένα διεθνές πρακτορείο τύπου κι εκείνος αναλαμβάνει την σύνταξη μιας σειράς άρθρων που θα πουληθούν σε εφημερίδες και περιοδικά. Είναι μάλλον ο καταλληλότερος: στοιχειώνεται από την ανάλογη πράξη του πατέρα του, στην ηλικία των τριάντα τριών και αναζητά τις δικές του απαντήσεις. Γύρω του κινούνται τρεις γυναίκες, η σύζυγός του (με την οποία βρίσκεται σε έντονη φιλονικία ύστερα από την επιμονή του να μοιραστεί σχετικό ερωτηματολόγιο στους μικρούς της μαθητές), η συνεργάτης του Μαρσέλα (μια ιδιόμορφη σχέση έλξης και απώθησης) και η μεγαλύτερη Μπίμπι ή αλλιώς «Αρχειοθήκη».

Ο αφηγητής ισορροπεί σε τέσσερα πεδία. Πρώτα βρίσκεται σε διαρκή κίνηση, καθώς σπεύδει στους τόπους της αυτοκτονίας, συνομιλεί με τους συγγενείς, ερευνά όλα τα σχετικά δεδομένα, μέχρι τα αρχεία των αγνοουμένων και τα πρωτόκολλα των αυτοψιών. Έπειτα καλείται να επιλύσει ένα αστυνομικό μυστήριο: μια μυστική εταιρεία που αφαιρεί το χέρι ενός αυτόχειρα. Από την άλλη, προσπαθεί να ισορροπήσει στην προσωπική του ζωή: εμπλέκεται με την ζωή της οικογένειας του αδελφού του και επισκέπτεται συχνά την μητέρα του, από την οποία ζητάει να συμπληρώσει τις καταχωνιασμένες του στο παρελθόν εικόνες. Στο τέταρτο βρίσκεται μόνος του στον προβληματισμό του για την έσχατη πράξη αλλά και την έλξη του προς την σχετική ιδέα.

Τα στοιχεία σταδιακά απαρτίζουν μια ιστορία της αυτοκτονίας, όπου μελετώνται τα πάντα: η παραλλαγή των τρόπων – οι γυναίκες προτιμούν το γκάζι, το υδροκυάνιο, τα υπνωτικά και μερικές τον απαγχονισμό· η ποικιλία των λόγων – ο έρωτας ή η έλλειψη έρωτα, η ντροπή και η υπερηφάνεια, οι ιδέες και ο μυστικισμός· η διάκριση των ιδιοτήτων – οι μορφωμένοι και οι ευκατάστατοι στα υψηλότερα ποσοστά· οι χώρες με τους περισσότερους αυτόχειρες: πάντα στην κορυφή η Γερμανία, πρώτα η Ανατολική Γερμανία, μετά η Δυτική.

Κάθε λογικός άνθρωπος έχει κάποτε σκεφτεί την αυτοκτονία έγραψε ο Αλμπέρ Καμύ, άρα και ως προς τα πρόσωπα ο κατάλογος των κατηγοριών δεν έχει τελειωμό: αυτοκτονίες από μίμηση, αυτόχειρες που περιμένουν κάποιον να τους σώσει, εκείνοι που αποχαιρετούν τα πρόσωπα και τα πράγματα, οι πολιορκημένοι που προτιμούν να πεθάνουν, για τους οποίους ο Μονταίν έγραψε όλα όσα κάνει κανείς για να γλιτώσει από το θάνατο, το έκαναν εκείνοι για να ξεφύγουν απ’ τη ζωή. Και τα μη έλλογα όντα που δεν αυτοκτονούν επειδή τα ίδια αγνοούν ότι θα πεθάνουν και εν πολλοίς δεν γνωρίζουν πως θα μπορούσαν να πεθάνουν ηθελημένα. Ή τελικά κάθε περίπτωση είναι μοναδική, όπως η μπορχεσιανή Αδριάνα Πισάρρο;

Ζούσε με το φόβο ότι δεν ήταν μοναδική, ότι πολλαπλασιάζεται: εκείνη ήταν οι άλλοι. Αν συζητούσε με έναν άνθρωπο, εκείνη γινόταν αυτός ο άνθρωπος. Αν πήγαινε στο θέατρο, η ηθοποιοί και οι θεατές ήταν εκείνη, εκείνη πολλές φορές. Όλους αυτούς τους ανθρώπους στους οποίους πρόβαλλε τον εαυτό της, τους θεωρούσε εχθρούς. Ήταν φορές που εξαφανιζόταν: δεν έβρισκε τον εαυτό της, ούτε στον καθρέφτη, ούτε στο κρεβάτι, ούτε μες στα ρούχα της. Σ’ αυτήν την περίπτωση ο τρόμος της δούλευε αντίστροφα: δεν ήταν ούτε μια ούτε πολλές. Ήταν λιγότερο από μία, είχε σβηστεί απ’ τον κόσμο. [σ. 75]

Στην εξωτερική ζωή του ο αφηγητής τρέχει ως άλλος ντετέκτιβ στους λόφους για δυο φοιτητές που σκοτώθηκαν μαζί, παρατηρεί ότι οι αυτόχειρες έχουν το φόβο στα μάτια τους, εντούτοις στα χείλη τους σχηματίζεται μια έκφραση αιώνιας ευχαρίστησης και μπερδεύεται όταν βρίσκει τα βλέφαρα κλειστά, να του στερούν την έκφραση του βλέμματος. Κι εκείνοι που επιλέγουν το κρεβάτι; Τι αντιπροσωπεύει γι’ αυτούς τους ανθρώπους το κρεβάτι; Είναι ένα σύμβολο της μοναξιάς τους; Τι υπονοεί γι’ αυτούς: κάτι το βαθιά προσωπικό και οικείο, τον έρωτα, την ανάπαυση, τη χώρα των ονείρων, την επιστροφή στη μητρική αγκαλιά; [σ. 122]

Τα ερωτήματα διαρκώς ανοιχτά: Κάποια σημειώματα ζητούν στην ουσία βοήθεια; Η αποσιώπηση του θανάτου από τους γονείς προς τα παιδιά είναι στην ουσία η προβολή του δικού τους φόβου; Και τελικά αποκρυπτογραφείται το αίνιγμα της αυτοκτονίας; Αναπόφευκτα όμως ο αφηγητής θα βρεθεί αντιμέτωπος με πιο φλέγοντα ερωτήματα: γεννιόμαστε με τον θάνατο μέσα μας; Ένας αυτόχειρας στην οικογένεια πολλαπλασιάζει τις πιθανότητες μίμησης στους επίγονους; Ο Ντυρκέμ έγραψε πως σε οικογένειες στις οποίες σημειώνονται αυτοκτονίες κατ’ επανάληψη, αυτές αναπαράγονται σχεδόν με τον ίδιο τρόπο.

Παράλληλα συντάσσεται σιγά σιγά μια εγκυκλοπαίδεια των φιλοσοφικών θέσεων για την αυτοκτονία αλλά και δοκιμάζεται ένα σύντομο ταξίδι πάνω στην σκέψη της ίδιας της λογοτεχνίας: από τον Δημοσθένη στην Σαπφώ, από τον Στέφαν Τσβάιχ στον Κυρίλωφ του Ντοστογιέφσκι, τον Βέρθερο του Γκαίτε και την Άννα Καρένινα· από εκείνους που την απορρίπτουν (Δάντης, Σαίξπηρ, Καντ, Σπινόζα), σ’ εκείνους που την αποδέχονται (Βούδδας, Διογένης, Σενέκας, Μονταίν, Ρουσσώ, Χέγκελ, Νίτσε, Χιούμ, Σοπενχάουερ – που έγραψε ότι «το μεγαλύτερο δικαίωμα του ανθρώπου είναι να μπορεί να δώσει τέλος στη ζωή του»). Ο ερευνητής του οικείου θανάτου καταγράφει με ζήλο τις απόψεις των θρησκειών και τις καταδίκες των εκκλησιών και όλα τα δεδομένα για εκείνη την «δειλία που απαιτεί πολύ θάρρος», όπως έγραψε ο Κίρκεγκαρντ.

Στο τέλος χάσκει πάνω στην οικειοθελή πράξη του πατέρα του: Στο πορτρέτο του έχει μείνει πάντα νέος· δεν θα γεράσει ποτέ. Να περιμένει κανείς τον θάνατο ως συνταξιούχος ή να τον προκαλέσει μόνος του; Κάποιες σκέψεις συνηγορούν υπέρ της φυγής: «Δεν μπορώ να σκοτώσω, τουλάχιστον όχι όλους. Μπορώ όμως να τους κάνω όλους να χαθούν: αν βυθιστώ στην ανυπαρξία, δεν θα υπάρχουν πια οι άλλοι για μένα».

Από το μικρό πορτρέτο, ο μπαμπάς, με ένα βλέμμα διαπεραστικό και ανήσυχο, παρατηρεί. / Θα μπορούσε άραγε να φανταστεί μπροστά στον φωτογράφο, πως με αυτή την άγρυπνη ματιά προς το φακό, θα μας κοίταγε για πάντα πίσω απ’ το τζάμι της κορνίζας; / Η μορφή μου αντανακλάται στο τζάμι και μου δημιουργείται η εντύπωση ότι από το σώμα μου έχει εξέλθει η εσωτερική μου εικόνα, που είναι όμοια με την εξωτερική, και επιθυμεί να τρυπώσει μες στη κόγχη. Στέκεται όμως στο γυαλί, δεν διαπερνά την επιφάνειά του, και αυτή είναι η ενδιάμεση ζώνη, ανάμεσα στο έξω και το μέσα. [σ. 167]

Θα περίμενε κανείς ύστερα από τα σχετικά δεδομένα του πολιτιστικού – λογοτεχνικού κλίματος της Αργεντινής που έζησε, ότι η γραφή του Μπενεντέττο θα ήταν συναρμονισμένη με το μοντέρνο λατινοαμερικανικό μυθιστόρημα της δεκαετίας του ’60 κι ότι θα βρισκόταν και αυτός σε εκείνον τον καταιγιστικό κύκλο. Όμως όχι: το ύφος του είναι λακωνικότατο, η γραφή ρεαλιστική, η εξέλιξη του μύθου γραμμική – τουλάχιστον σε αυτό το δείγμα που διαβάζουμε τώρα.

Ο συγγραφέας απάχθηκε από τον στρατό από τα γραφεία της εφημερίδας του λίγες μόνο ώρες μετά το πραξικόπημα του Βιντέλα παρέμεινε στην φυλακή για δεκαεννέα ολόκληρους μήνες, χωρίς ποτέ να του δοθούν εξηγήσεις για την κράτησή του. Τα βασανιστήρια και οι εικονικές εκτελέσεις έκαμψαν για πάντα τη σωματική και πνευματική του υγεία. Μετά την απελευθέρωσή του από τις φυλακές της αργεντινής δικτατορίας ο συγγραφέας και εξορίστηκε στην Ισπανία, απ’ όπου επέστρεψε στην Αργεντινή λίγο πριν από το θάνατό του. Εκτός από μυθιστορήματα και διηγήματα ο ντι Μπενεντέττο [1922 – 1986] έχει γράψει σενάρια για τον κινηματογράφο. Οι αυτόχειρες αποτελούν το τρίτο μέρος ενός είδους τριλογίας [Trilogía de la espera] και μεταφέρθηκαν στον κινηματογράφο το 2006 από τον Juan Villegas.

Εκδ. Απόπειρα, 2014, μτφ. – σχόλια: Άννα Βερροιοπούλου, 177 σελ. [Antonio di Benedetto, Los suicidas, 1969].

Βιβλιοπανδοχείο

A Sunny Outlook for ‘Weather’ on Exoplanets (NASA)

Bupalus and Athenis

Bupalus and Athenis from “Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum “

Bupalus (Greek: Βούπαλος) and Athenis (Greek: Ἄθηνις), were sons of Archermus, and members of the celebrated school of sculpture in marble which flourished in Chios in the 6th century BC. They were contemporaries of the poet Hipponax, whom they were said to have caricatured. Their works consisted almost entirely of draped female figures, Artemis, Fortune, The Graces, when the Chian school has been well called a school of Madonnas. Augustus brought many of the works of Bupalus and Athenis to Rome, and placed them on the gable of the temple of Apollo Palatinus. Bupalus supposedly committed suicide out of shame after Hipponax wrote caustic satirical poetry about him to revenge himself on Bupalus for his refusal to let Hipponax marry his daughter and for his caricature of Hipponax.

Aristophanes refers to Bupalus in The Lysistrata. When the Chorus of Men encounter the Chorus of Women near the north-western edge of the Acropolis they ridicule the women, “I warrant, now, if twice or thrice we slap their faces neatly, That they will learn, like Bupalus, to hold their tongues discreetly.” (Benjamin Bickley Rogers translation)

It is now suggested that the north (and perhaps also the east) frieze of the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi was the work of Bupalus, based on a partially erased inscription around the circumference of one of the giant’s shields, reconstructed as:

Ḅ[όπαλ]ο[ς Ἀρχέρμο̄? τά]δε καὶ τὄπισθεν ἐποίε

Boupalos son of Archermos made these (sculptures) and those behind.

WIKIPEDIA

Bupalos and Athenis (active ca. 540-ca. 537 BC)

Greek sculptors

- Rumored to have been driven to suicide by the nasty, albeit poetic, written attacks of Hipponax (who apparently didn’t like their sculpture of him).

THOUGHTCO

‘The First Poets’: Starting With Orpheus

THE FIRST POETS Lives of the Ancient Greek Poets. By Michael Schmidt. 410 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $30.

Ancient Greece is the fountainhead of Western culture and politics. As Michael Schmidt demonstrates in “The First Poets,” the evolution from aristocratic rule to democracy in Greece was accompanied by the emergence of a strongly individualistic lyric poetry. While the Hebrew Bible, the other major source of Western literature, expresses a God-centered view of the universe, Greek literature gradually freed itself from the sacred to focus on the uniquely human voice.

Schmidt is the editor of PN Review, the founder and director of Carcanet Press and the director of the Writing School at Manchester Metropolitan University in England. His widely praised book “Lives of the Poets” (1998) was a 900-page meditation on English poetry in which his forceful, witty, sometimes partisan sketches revealed a mind deeply in love with literature.

In “The First Poets,” however, Schmidt seems less confident of his opinions. He is excessively deferential to authorities, even when gently rejecting their views. It is always a pleasure to encounter the lucid, astute prose of the late Sir Cecil Maurice Bowra (Schmidt’s don at Oxford), but this book is clogged with too many pedestrian quotations from academics past and present. Whenever he is front and center, Schmidt himself is a fascinating guide who wins the reader’s trust.

“The First Poets” covers about a half-millennium of writing up to the third century B.C. Its chronological organization is ideally suited for those seeking an introduction to Greek poetry, although the book needs better maps of the Mediterranean world. Drawing on translators from John Dryden to Guy Davenport, Schmidt deftly explains the problems in translating “vowel-rich” ancient Greek into English, which cannot capture Greek’s falling rhythms and vocal pitch.

A constant theme is the tragically fragmentary nature of the Greek poetry that we have. Only a fraction has survived, much of it by chance — perhaps because it was quoted in an ancient letter or essay. Because of the fragility of papyrus and parchment, Greek literature was decaying by the Roman era. Schmidt stresses what we owe to the Egyptian desert, where papyrus discoveries are still being made in mummy wrappings and trash heaps. Ancient Greek poems today are often merely tentative scholarly reconstructions.

Schmidt has a sharp eye for material culture: he notes, for example, how the fine grain of papyrus (made from Nile reeds) promoted the development of writing because it gave “the ability to vary letter-forms.” Many modern words for books descend from antiquity, when papyrus scrolls — some up to 100 yards long — were used for storage. A “volume” (from the Latin volumen) literally means “a thing rolled up.”

The book’s profiles begin with Orpheus, the legendary father of poetry and music, whom Schmidt boldly treats as a real person: “I take Orpheus to have been an actual man with an actual harp in his hand.” After his wife, Eurydice, was lost in Hades, Orpheus turned to boy-love and was reputedly the first to practice it in his native Thrace. His death was gruesome: he was torn to bits by bacchants, and his severed head floated to the island of Lesbos, which was thereby impregnated with poetic genius.

Schmidt’s chapters on Homer, while rich, seem too long for a survey book — and we’re still at the start of the “Odyssey” on the next-to-last page. Far more interesting than the excessive plot summary is Schmidt’s treatment of Homeric diction as “a composite of different dialect strands . . . as though a poet wrote in Scots, South African, Texan and Jamaican, all in a single poem.”

Much attention is devoted to controversies over the authorship of the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey”: Was Homer a myth? Did one man (or even a woman) compose both poems? Was Homer merely a collator of inherited material? Schmidt makes Homer concrete by taking us on a lively fictionalized odyssey through his hypothetical life and experiences. As for those who allege there were two poets, Schmidt rightly scoffs, it’s “as though Shakespeare could not have written ‘The Comedy of Errors’ and ‘Othello.’ “

To deny Homer’s existence, Schmidt argues, “impoverishes our reading.” Regrettably, he doesn’t joust with the notorious “death of the author” dogma of literary poststructuralism. He oddly fails to describe the classicist Milman Parry’s pioneering use of recording technology to document survivals of the epic oral tradition in rural Yugoslavia in the 1930’s. And he hurries past an influential 19th-century theory that a single bard, long after the Trojan War, wove heroic lays of military adventure into two integrated poems — a process that would be repeated in medieval romances.

In his chapter on Hesiod, whose “Works and Days” and “Theogony” rivaled Homer’s epics for near-biblical status in Greek culture, Schmidt gives glimmers of the more reader-friendly book that might have been — an alluring, dreamlike travelogue of the Greek sites where ancient poets lived and created. “Even today it is no easy matter, getting to where Hesiod’s farm used to be,” he says. Hiking through a parched landscape up Mount Helicon, he sees “old olive trees clenched among the rock” and is surprised by “tiny gusts of exquisite scent” from the “wild, almost leafless cyclamen, pale dots of purple.”

With Archilochus, Schmidt hits his stride. “The only Greek soldier-poet we have,” Archilochus was born on wind-swept Paros, famed for its translucent marble. As a young man, he was leading a cow to market when the Muses appeared, stole the cow, and left a lyre in its place. Archilochus became a brazen sensualist, caustically irreverent. Schmidt calls him a “cad,” a cruel exploiter of women and “an early defining figure of patriarchy”; his imagery has “a reptilian eroticism.”

Alcman, who labored for Sparta, provides an eloquent contrast to cynical Archilochus. The “I” of Alcman’s “civic” choral poetry was collective. Schmidt compares Alcman’s work to masques like Milton’s “Comus,” where poetry and music are interwoven. Alcman’s poems were “sung not in the intimacy of the symposium,” a male dinner party, he writes, “but in the open, public air.” Schmidt also laments Sparta’s cultural decline. Famous in the seventh century B.C. for its “music, pottery and poetry,” it became an imperial power so besotted by militarism that “three centuries later, the adjective ‘Spartan’ had become synonymous with ‘Philistine.’ “

Next we meet Mimnermus, whom Schmidt calls “an elegist of pleasure,” and the misogynous Semonides, who sees woman as sow, vixen and bitch. Then come the great poets of Lesbos, Alcaeus and Sappho, both aristocrats born during the politically unstable early seventh century. Schmidt calls Alcaeus “a brilliant poet of wine” and “debauchery” but also “a survival poet, enduring exile and hardships.” Ancient writers assumed he “preferred the company of his own sex.”

In a substantial but uneven chapter on Sappho, Schmidt intriguingly speculates on where she was born and raised on Lesbos (a large island near the coast of Asia Minor): was it in the western village of Eressus in rough, barren country, or in the cosmopolitan eastern seaport of Mytilene? He subtly evokes her poetic style: “Sappho’s art is to dovetail, smooth and rub down, to avoid the over-emphatic.” And he aptly compares the relationship between voice and musical accompaniment in Sappho’s performance of her poems to the recitative in opera.

But although he acknowledges the way Sappho has “appealed to the sexual prurience or moral severity of centuries of scholars and readers,” Schmidt doesn’t adequately summarize the passionate arguments over Sappho’s character, public life and sexual orientation. He omits altogether the role played by the medieval church in burning her manuscripts. While Swinburne’s darker rewriting of Sappho is quoted (with minimal comment), Catullus’ far more important version receives only a passing mention. As for Sappho’s two brilliantly original major poems, “He Seems to Me a God” receives less than a page of attention, and “Ode to Aphrodite” is barely glanced at. Instead, Schmidt wastes space with long, dreary quotes from a feminist classicist stuck on the usual dated ideology of male oppression.

The lawgiver Solon was the first poet of Athens. His was “a language of distilled moral truth” that had what Schmidt calls “a humorless pithiness.” Solon’s maxims, “Moderation in all things” and “Know thyself,” were carved on Apollo’s temple at Delphi.

There were two poets named Anacreon. The “false” one inspired the carpe diem (“seize the day”) tradition of “creature pleasures” of sex and appetite that would so enchant European literature. The real Anacreon was “drawn to boys” and died from inhaling a grape pip. He was honored in a robust nude statue on the Athenian Acropolis.

The poet Hipponax, Schmidt writes, shows “the human body at its most gross”; he is “obsessed with food, sex, excretion” and “a cruising lust.” His poetry, with its “smells” and “obscene diction,” has “the repulsive fascination of toilet-wall graffiti.” Hipponax influenced Aristophanes’ farcical comedies and possibly Petronius’ decadent “Satyricon.”

Simonides, a shrewd operator, was the first poet to get rich from selling his work. Corinna’s narrative poetry was so admired that she was said to have been Pindar’s teacher and rival (though she lived long afterward).

Pindar’s ornate, visionary odes are untranslatable. Commissioned to praise athletic victors or memorialize gifts, they are, Schimdt says, “the extremity of art,” moving “towards timelessness or abstraction.” He calls them “a texture of cross-referencing” and “an almost continuous string of metaphors.” The odes of Pindar’s rival, Bacchylides, were lost until a smashed papyrus scroll of his work was discovered in Egypt in the 1890’s and reassembled at the British Museum.

After Pindar, Schmidt writes, lyric poetry lost vitality, and “verse thrived primarily in the drama.” In the new Hellenistic world inaugurated by the conquests of Alexander the Great, “cultural authority” shifted from Athens to Alexandria in Egypt, where poetry now “lived in libraries”: “What had been language responding to nature, history, the social world, began to become language responding to prior language.” The poet Callimachus, for example, was a librarian, “the father of bibliography.” His cataloging lists, or canones, became our “tyrannical canonical texts.”

Schmidt paints a vivid portrait of bustling Alexandria with its “racial mix” and “mess of languages and dialects.” There Theocritus invented the pastoral idyll, a sentimental fantasy of happy, singing shepherds that would remain chic until the era of Marie Antoinette. Themes of boy-love and “open-air buggery” are also part of Theocritus’ legacy. For Schmidt, Theocritus was emblematic of radical changes in Greek literature. His poetry was no longer sung for a live audience. Now written down, it addressed “a creature who hardly existed in Homer’s day, the reader.”

Camille Paglia is the university professor of humanities and media studies at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Her most recent book is “Break, Blow, Burn: Camille Paglia Reads Forty-Three of the World’s Best Poems.”

NEW YORK TIMES

NASA Telescope Discovery Satellite Interview

Crevel, René (1900-1935)

French Dada and Surrealist poet

- Gassed himself the day before the Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture met in Paris.

THOUGHTCO

The golden boy of Surrealism

by

If you look at the photograph of leading Surrealist artists and writers, taken in 1932 at Tristan Tzara’s, you will find René Crevel in the back row, and that is where he long remained. The others, including Andre Breton, Salvador Dali, and Paul Eluard, all seem to know what to do with their hands, whereas René Crevel is leaning forward, one hand placed for support on the shoulder of Max Ernst, the other on that of Man Ray. Born in 1900, the golden boy of the Surrealist movement, Crevel is perhaps remembered more for having killed himself than for his writings, though even in death he is surpassed by other suicides, by the revolver-brandishing Jacques Vaché, for instance, whose myth was sedulously fostered by Andre Breton. Why, then, has David Rattray chosen to publish now a translation of Crevel’s autobiographical novel, La Mort difficile, sixty years after its first appearance in 1926?[1] The answer to that question may well have as much to do with a certain climate of opinion that has flourished since the Sixties as with Crevel’s undoubted talent as a writer.

It was in 1947 that Jean-Paul Sartre accused the Surrealists, who deeply influenced him, of being young men of good social position who were hostile to daddy. Crevel senior, however, hanged himself in 1914, and his young son was left under the domination of a mother he loathed and who is caricatured as the odious and pretentious Mme. Dumont-Dufour in La Mort difficile. Still, unlike many of the budding Surrealists in the Twenties, Crevel was indeed well-to-do and well connected. He was a great friend of the Vicomte Charles de Noailles and his wife Marie-Laure, who financed the notorious film, L’Âge d’or, by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali; and it was he who introduced the inventor of limp watches to one of the earliest of that artist’s princely patrons.

Crevel appears indubitably handsome in the portrait photograph by Man Ray, and in fine line drawings of the period. His looks were of a type that should have given him a role in one of Cocteau’s later films, had he survived and if Breton and Cocteau had not been at daggers drawn. One of Crevel’s friends, the Surrealists’ ally, André Thirion, remarked in his memoirs on the engaging personality and polished charm of the author of La Mort difficile. André Breton’s portrait of his associate is more somber: it stresses the disquiet and the complexity of the young man’s character.

In his books Crevel made no secret of his homosexuality or bisexuality. As for Breton, he wrote paeans to heterosexual love, and like most of the Surrealists he viewed homosexuality with disfavor, although the colleagues tolerated what they regarded as an aberration in their friend. It is plain from Crevel’s highly personal narrative, Mon Corps et moi (“My Body and Me”), that the young author felt deeply divided about his sexual proclivities. Moreover, he had long suffered from ill health: tuberculosis took him at frequent intervals to boredom in Swiss sanatoria, and his sickness was complicated by alcohol and drugs (opium, cocaine). The theme of suicide haunted him. In his very first book, Détours (1924), he imagined the scenario of death by gas that he was to follow eleven years later in 1935. With Man Corps et moi, he betrays his doubts about the reality of his own existence.

The great event of Crevel’s life was his meeting with André Breton in 1921: a strong, aggressive character under whose aegis the Surrealist enterprise often appears as a succession of insults, cuffs to celebrated heads, and expulsions. Crevel made an important contribution to the movement and yet he also figures as its victim. Having been initiated into spiritualism by an aristocratic English lady, he introduced Breton to “hypnotic sleep,” which played so large a role in the development of Surrealism and its use of automatic writing or image-making. In a deep sleep, Crevel declaimed, sang, yet apparently he had no memory of what had passed. These experiments led the young writer to try to hang himself, and Breton put an end to them. In the famous “Inquiry into Suicide,” conducted by La Révolution surréaliste, Crevel eloquently justified suicide as a solution to his dissatisfaction with his life.